Do Russian investments in Europe help further the country’s interests when it comes to political decision-making? Drawing on a new study, Sara Norrevik presents evidence that MEPs representing areas that receive high levels of investment from Russia are more likely to have voted against closer EU-Ukraine ties in the European Parliament.

Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) into the European Union from major foreign powers has caused concern in Brussels and European capitals in recent years. For example, when Nord Stream 2 – the gas pipeline through the Baltic Sea – was completed in September 2021, new questions surfaced about delivery of natural gas from Russia to Germany. Similarly, China’s investments in Europe are under the spotlight after Beijing leveraged post-financial crisis restructuring in crisis-ridden member states to gain access to important infrastructure.

An example is Greece’s port of Piraeus, Europe’s largest passenger port, which has majority Chinese ownership, leading some analysts to suggest that Beijing has bought political influence in Athens. Foreign ownership in areas of technology such as artificial intelligence, robotics, semiconductors, and dual-use items in Europe has also caused alarm in policy circles. Member states have faced pressure internally and externally – in particular from the US – to drop Chinese telecom giant Huawei from building national 5G networks.

In response to FDI security concerns and risks, the EU has adopted an investment screening mechanism, implemented in October 2020, aimed at scrutinising FDI from non-EU countries in sensitive industries and critical assets. The approach is in line with a broader global trend to protect domestic industries from control by foreign adversaries. Yet, the EU regulation is far from the vetting system in place in the United States that was strengthened in 2018. It also lacks the muscle of mechanisms adopted by individual EU member states to review foreign investments – around half of EU states had adopted such mechanisms prior to the EU-wide regulation. Retaining power to decide on the screening of foreign investments, member states can share information and coordinate their actions on foreign investments under the new EU regulation.

The motivations for establishing a coordinated investment screening mechanism stem primarily from national security concerns such as critical assets falling under the control of rival foreign powers. For instance, early in the Covid-19 pandemic, public health concerns triggered the Commission to issue guidance on foreign investment screening to preserve critical assets in public health, medical research, biotechnology and infrastructure.

Next to security risks and public health concerns, EU member states may also consider the potential for major foreign powers – including adversaries – whose multinationals are investing in Europe to gain political influence. This influence is particularly concerning when FDI comes from state-owned or state-influenced corporations, which is the case for a large share of investments from Russia and China. Over time, foreign investment creates economic interdependence with the foreign power which can be leveraged to favour foreign interests in EU policies.

Russian investment and the voting records of MEPs

In a new study, I find evidence that FDI from major powers into EU member states makes politicians from regions that receive these investments more likely to support the interests of the foreign power. I show a statistical association between Members of the European Parliament voting on policies toward EU-Ukraine cooperation and the level of FDI from Russia in their electoral districts.

MEPs have veto power over EU-Ukraine economic cooperation and are therefore powerful actors in this sub-field of EU foreign policy – in contrast to economic sanctions, another policy important to Russia, which MEPs cannot veto. As Vladimir Putin wants Ukraine to belong to Russia’s sphere of influence and the Eurasian Economic Union instead of the EU, the Kremlin strongly opposes EU-Ukraine cooperation.

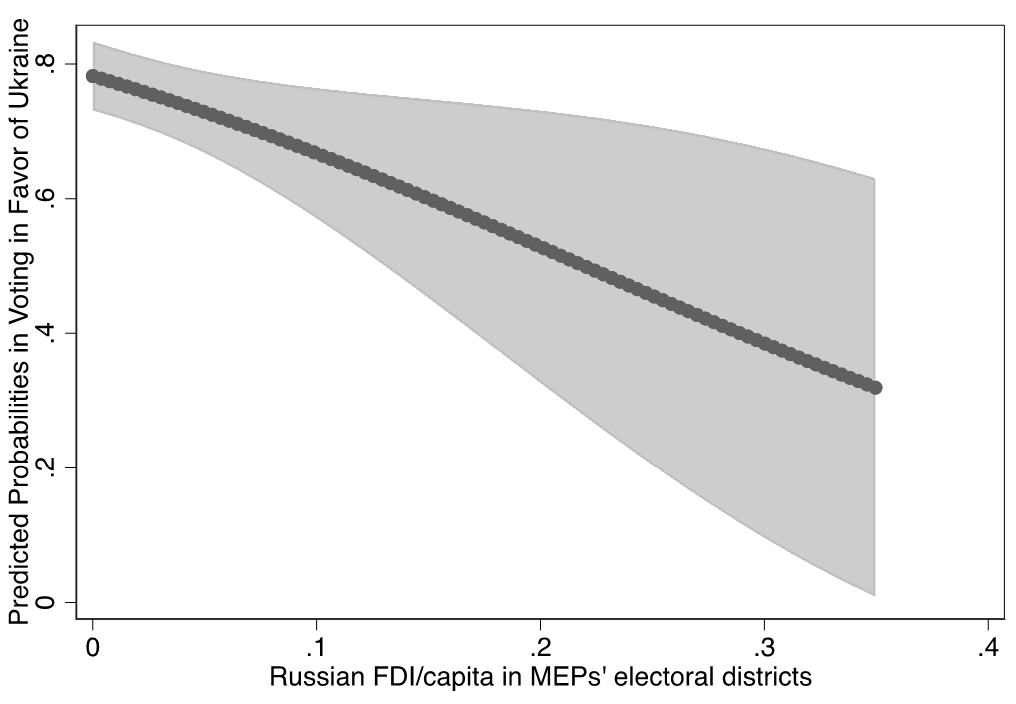

By analysing voting records in the European Parliament in the years following the outbreak of the Ukraine conflict in 2014, I found evidence that MEPs with higher levels of Russian FDI in their electoral districts were more likely to take a pro-Russian policy position than those who received low levels of FDI. Data on FDI from Russia into EU member states was collected (specifically, aggregated greenfield investments over a five-year period prior to the vote) and broken down to district levels that are compatible with European Parliament districts for countries that had subnational EP districts. The results are shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Relationship between Russian foreign direct investment and the probability of an MEP voting for EU-Ukraine cooperation

Note: The figure plots the predicted probabilities of voting in favour of EU-Ukraine cooperation at different levels of FDI/capita in electoral districts. An increase in Russian FDI/capita from 0.05 to 0.10 (a difference of US$50) equals a decrease in the odds ratio of supporting EU-Ukraine cooperation of 0.07, on average, and the result is statistically significant.

Since Russian FDI is to a large extent influenced by the Kremlin via companies such as Gazprom, Yukos and Rostec, MEPs representing areas receiving high levels of FDI may not want to worsen relations between Russia and the EU and risk losing investments in their districts. MEPs are aware of the high degree of political control of Russian multinational corporations. By aligning themselves with Russia on important foreign policies, they can protect job opportunities in their districts and avoid a political backlash.

Recent scholarship shows that foreign meddling is common among major powers. Economic interdependence, in particular, is used by foreign powers to leverage political influence abroad. Case studies suggest that Russia leverages economic interdependence to advance foreign policy interests in Europe, along with other instruments.

The results of my study can also be tied to studies on economic networks that are used to coerce other nations, a phenomenon described as weaponised interdependence. Similarly, in the field of sanctions, scholars have detected a relationship between economic interdependence with a foreign power and an unwillingness among policy-makers to impose sanctions against that power.

My findings highlight that large-scale FDI from major powers, such as Russia and China, has policy consequences that go beyond the immediate investment. Based on the results of my study, policymakers are likely to become more vulnerable to political influence from these nations when FDI is located in their regions. To tackle the risk of foreign influence over EU policies, the EU may consider sharpening its current mechanism of screening FDI from major powers.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper in European Union Politics

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: © European Union 2014 – European Parliament (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)