The Covid-19 pandemic has put health care at the centre of the political agenda, but does this mean that citizens are now more willing to support increased health spending? Drawing on detailed survey evidence, Marius R. Busemeyer explains how support for health care spending has changed in Germany during the pandemic.

The Covid-19 pandemic represents a challenge of historic proportions for health care systems around the globe. In spite of continuing progress in vaccinating a growing share of the population, health care systems continue to be under strain as resurgent infection waves have led to an increase in the number of patients in hospitals.

Germany’s performance during the Covid-19 pandemic has been mixed, but relatively successful overall. Compared to neighbouring countries, infection numbers (and the number of fatalities) have remained below average. Public support for lockdowns and other pandemic-related measures has remained relatively high throughout the crisis, while the stringency of measures has been less severe compared to other European countries.

However, the effectiveness of Germany’s crisis response was hampered by its federalist political system. On the one hand, the federalist constitution allowed for a more regional and local approach to fighting the pandemic. On the other, regionalism at times impeded a coordinated policy response across the whole of Germany, resulting in foot-dragging among policy-makers and a decline in overall public confidence in the system’s effectiveness. This was especially true in early 2021 when the public mood soured because of the slow start of the vaccination campaign, the emergence of a number of corruption scandals related to the sale of masks and other protective gear in the governing party, and a generally uncoordinated response to the winter and spring infection waves.

The pandemic and support for health care spending

What impact (if any) have these events had on public support for increased public spending on health care in Germany? Even before the onset of the crisis, public opinion data showed that the German population perceived a strong need for significant reforms in the health care system, including increased public investments in this sector. According to the latest available comparative public opinion data from the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) from before the crisis, about three quarters of the German population supported more or even much more spending on health care. Furthermore, high support for additional spending is associated with merely average levels of overall satisfaction with the system.

The pandemic has both highlighted the strengths of German health care and brutally revealed its shortcomings. For one, the above average number of beds in Intensive Care Units (ICUs) – an issue that had been criticised before as wasteful overspending – prevented a breakdown of hospital care, as partly happened in other countries. The large number of general practitioners (GPs) and specialist doctors proved crucial in boosting the speed of the vaccination campaign in the spring of 2021. In contrast, the pandemic has shown severe underinvestment in the digitalisation of health care, in particular regarding the tracking of infections and available capacities in hospitals. Preventive aspects of health care, in particular related to the effective prevention of pandemics, remain underdeveloped as well.

Survey evidence

In a recent study, I analyse the extent to which the pandemic has affected public support for additional spending on health care. Even though, as briefly mentioned, public support had already been relatively high before the crisis, the issue of health care has usually not occupied the top spots as the “most important problem” on the political agenda.

This is clearly different in the context of the pandemic and the likelihood of high public support translating into actual policy changes may therefore be higher. Furthermore, the pandemic has laid open the weaknesses of the current health care system, hence it may be the case that public support for health care increases even further. Alternatively, the opposite effect may also occur: if citizens perceive the system as badly performing, they may be even more reluctant to commit additional tax money to it than before.

To answer these questions, I draw on the ‘Covid-19 and Social Inequality’ survey programme organised and financed by the Cluster of Excellence ‘The Politics of Inequality’ at the University of Konstanz. This survey consisted of three waves (April/May 2020, November 2020 and May 2021), with a total of about 7,400 individual responses across the waves (with about 2,200 individuals left in the third wave who participated in all three).

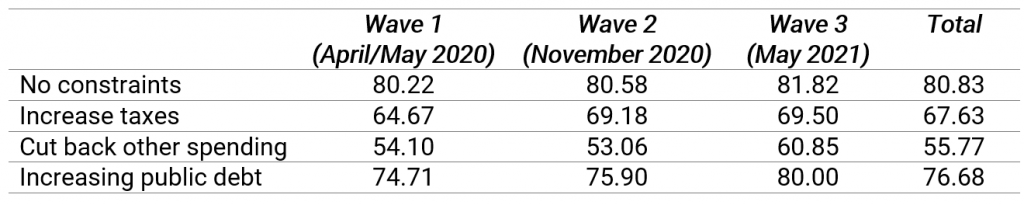

Regarding the measurement of public support for additional health care spending, the survey contains an important innovation, which follows other recent work in studying the politics of fiscal trade-offs. Rather than simply asking respondents for their overall support for additional spending, the survey mentions particular fiscal constraints that policy-makers (and therefore citizens as well) are likely to confront when expanding spending, namely to either increase tax, the level of public debt or face cutbacks in other parts of the welfare state. To avoid spill-over effects, the sample was divided into four equally sized groups, and each group only received one of these questions. Table 1 shows the descriptive data.

Table 1: Percentage of respondents that support ‘more’ or ‘much more’ spending on health care in Germany

Note: The table indicates how the level of support for public spending on health care changes when different constraints are mentioned.

A first important takeaway is that public support for additional health care spending has remained stable or even increased somewhat during the pandemic. This is an important finding because while support for additional spending has remained stable, the public perception of the ability of the system to deal effectively with the crisis has dropped significantly throughout this time. In the first survey wave, a relative majority of 52 percent had a positive view of the efficiency of the crisis response; this value increased slightly during the second survey wave, but then dropped significantly to about 29 percent in the third survey wave in May 2021.

The second takeaway is that fiscal constraints obviously matter. Not surprisingly, support for increased spending on health care is highest when no fiscal constraints are mentioned and lowest when spending increases would have to be financed by cutbacks in other parts of the welfare state, again mirroring previous findings. What is interesting, however, is that the differences between the different sub-groups slightly decrease for later survey waves, signalling that fiscal constraints increasingly matter less.

Improvement reaction

Taking these two issues together, a third finding emerges: a more detailed multivariate regression analysis shows that support for additional spending is particularly high among individuals who are critical of the current performance of the system.

This amounts to what Heejung Chung and Bart Meuleman have called ‘improvement reaction’, where rather than fully turning their backs on the health care system, critical citizens are more likely to support additional investments to ameliorate the (perceived) short-comings of the system. What remains to be seen is whether these demands for additional investments in health care will remain politically salient once the worst of the pandemic is over and other pressing short-term needs move to the top of the political agenda.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper in the Journal of European Public Policy

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Piron Guillaume on Unsplash