There is a general perception that the European Commission has become more politicised over recent decades. But is there evidence of politicisation in the language used by members of the Commission to communicate with the public? Drawing on a co-authored study using a corpus of 8,947 speeches delivered by members of the Prodi, Barroso and Juncker Commissions, Piero Tortola finds that contrary to expectations, the Commission’s language has become less politicised over time.

In his maiden speech before the European Parliament, on 15 July 2014, soon-to-be-confirmed European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker made a bold promise to his audience: his Commission would be “more political. Indeed… highly political.” Implied in the promise was the idea that, for the next five years, the Commission should be a key player in the definition of the European Union’s main political choices and direction, rather than a mere technical executor of decisions made elsewhere – chiefly the European Council.

Juncker’s statement arose out of a specific political and institutional juncture for the EU. For one thing, his was the first appointment made via the new Spitzenkandidaten procedure, which linked the selection of the Commission President to the outcome of the preceding European Parliament election, thus increasing the Commission’s democratic legitimacy. For another, Juncker took the helm of the Commission at a time when supranational political impetus was needed to tackle the aftermath of the Eurozone crisis as well as the new challenges stemming from the migration crisis, and geopolitical turbulence in the EU’s eastern neighbourhood.

Reflections on the more or less political nature of the Commission were, however, by no means new at the time of Juncker’s inauguration. Indeed, many observers had noted a gradual politicisation of the Commission for at least the two decades prior to Juncker’s tenure, as a result of such factors as the integration of core state powers (most notably monetary policy), the gradual ‘parliamentarisation’ of the Union – of which the Spitzenkandidaten mechanism was just the latest chapter – but also the increasing political profile of the individuals appointed as President and Commissioners.

What was new in Juncker’s words, though, was that they did not just point out the Commission’s politicisation, but also, in a way, embodied it. As with any social activity, politics – and therefore politicisation – are inextricably linked to language. This is more so for an inherently ambiguous (partly technical, partly political) institution like the Commission, whose language can give us important clues as to its attitudes and preferences. For this reason, it is surprising that Juncker’s utterances have never been followed up by a systematic analysis of the Commission’s language, to see whether and to what extent politicisation has occurred in the realm of communication.

In a recent study, Pamela Pansardi and I try to fill this gap by investigating the Commission’s linguistic politicisation based on a corpus of 8,947 speeches delivered by members of the last four Commissions to have concluded their terms: Prodi (1999-2004), Barroso I and II (2004-14) and Juncker (2014-19). To detect politicisation, we adopt two composite indicators related in opposite ways to it – charisma and technicality – which we turn into dictionary-based operational constructs using the DICTION 7 software.

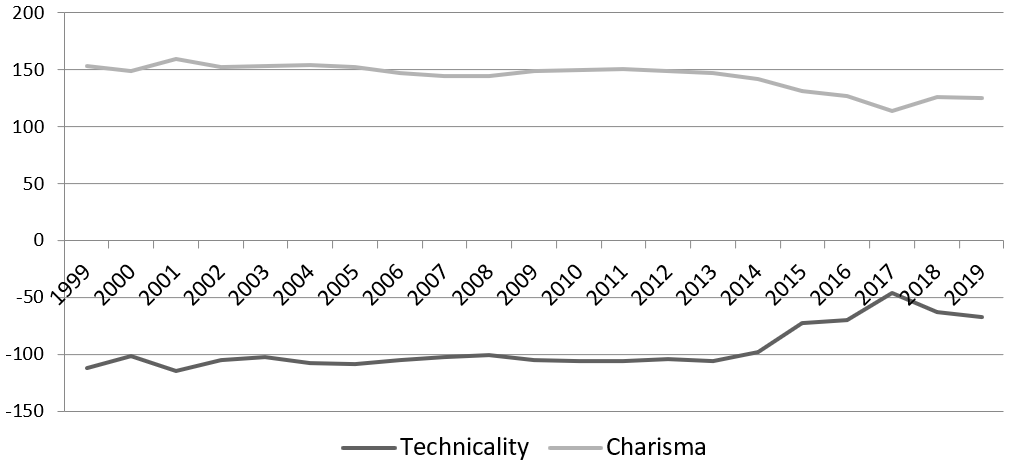

Figure 1 shows the yearly average values of the two indicators in Commission speeches over the two decades under consideration. Contrary to expectation, we observe a general downward trajectory of politicisation over time, which reached its nadir in the years of the Juncker Commission. In other words, when it comes to language, Juncker’s announcement of a highly political Commission seems disconfirmed by the data.

Figure 1: The European Commission’s linguistic charisma and technicality (1999-2019)

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper (co-authored with Pamela Pansardi) at the Journal of Common Market Studies.

To confirm our findings, we run statistical analyses of variance between the four Commissions, looking at the European Commission in its entirety, as well as isolating Presidents and colleges of Commissioners, respectively. As an extension of the latter analysis, we also examine linguistic politicisation over time by portfolio clusters, as a way to check for any sectoral biases in the use of language – for which we do not find significant evidence. All in all, our study confirms robustly that the language of the Commission has become less political over time.

What do our findings mean vis-à-vis the commonly held perception of an ever more politicised Commission? We suggest two, not necessarily exclusive, interpretations. The first is that language is to be seen as a dimension of politicisation on a par with the remaining ones defined in institutional, policy, and individual terms. In this case, the linguistic trends that we have observed should simply detract from overall Commission politicisation, and lead to the conclusion that, after all, the Commission has not become as politicised in recent years as many think.

According to the second interpretation, our findings do not contradict but instead reinforce the notion of an ever more political Commission. Language here is not just another sphere of politicisation, but a tool used strategically by the Commission to counter or underplay its increasingly political nature, so as to avert conflicts with member states, and mitigate the legitimacy issues that may arise from overt politicisation in the absence of a full-fledged democratisation of the Commission. This logic can also work in reverse: a more technocratically-oriented Commission may, in some instances, deploy more political language as a way to project a more assertive stance in the eyes of other political actors or the wider European audience.

Whatever the interpretation, our research highlights that politicisation is a more complex phenomenon than is often assumed, and cautions against quick and unidimensional assessments of this phenomenon. This also goes for the current von der Leyen Commission, whose appointment marked, for many, a return to a more low-profile model for the Commission, but which could well find alternative avenues of politicisation, especially in the fluid context generated by the Covid-19 pandemic.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper (co-authored with Pamela Pansardi) at the Journal of Common Market Studies

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council