Russian President Vladimir Putin has justified his decision to invade Ukraine by claiming that Ukrainian culture is closer to Russia than to Europe, and that the two countries are separated only by an artificial border. Tim Reeskens assesses this claim using data from the European Values Study.

In 2021 Vladimir Putin published an essay on the historical unity between Ukraine, Russia and Belarus; a unit that, according to Putin, is separated by an artificial border. Putin claims that the three countries not only share a past but also a future, and that Ukrainian culture is closer to Russia than to Europe.

It is undeniable that the countries inextricably share a past; however, the current president of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky, sees his country’s future as belonging to Europe. His call for membership of the European Union has been further supported by the President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen. However, do Ukrainian values really resemble those of the rest of Europe, or are they – as Putin asserts – closer to those of Russia?

A dividing line that splits Europe?

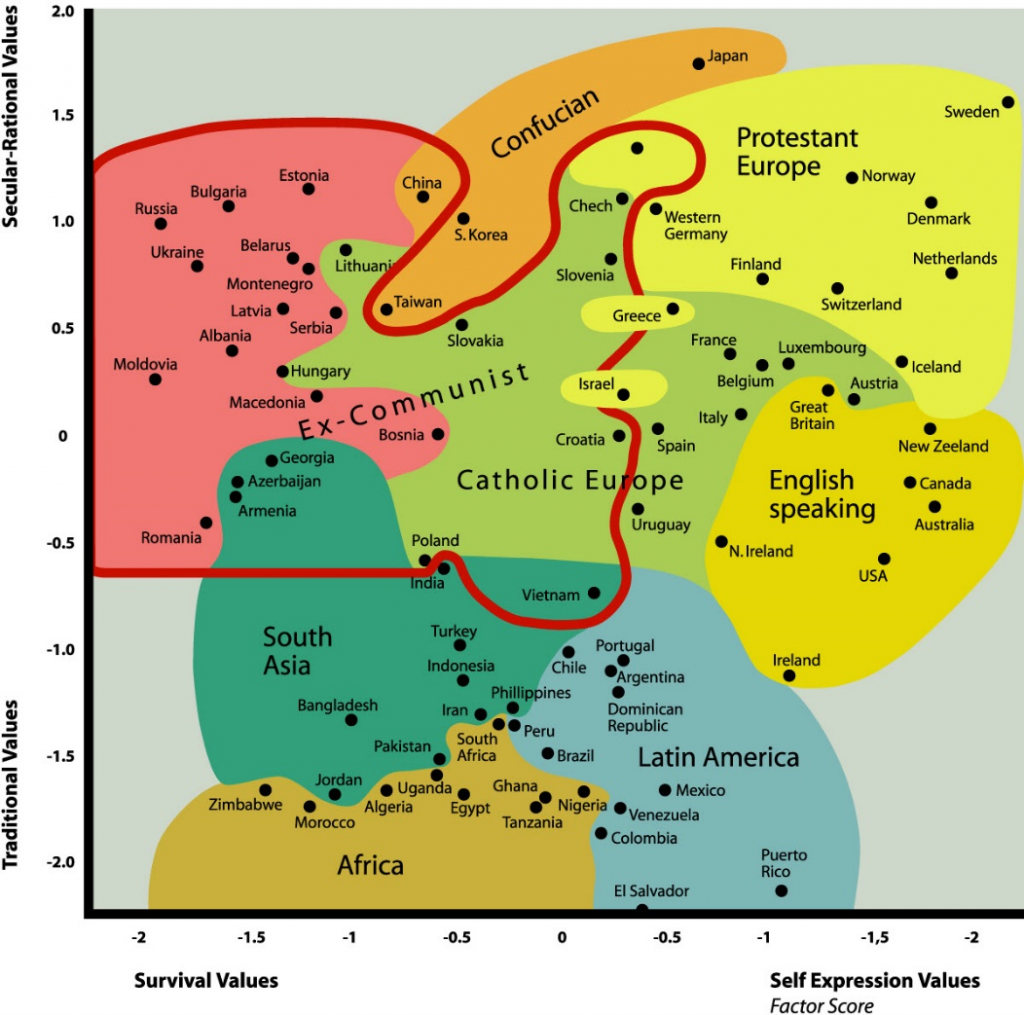

In comparative research into values, Ukraine is invariably placed close to Russia. In one of the first editions of the so-called Inglehart-Welzel ‘Cultural Map of the World’ (in which countries are classified according to two dimensions: survival values vs. self-expression values, such as tolerance, and traditional vs. secular values), we see Russia and Ukraine almost side by side. They fall in the red ‘Orthodox’ cluster, and are surrounded by the red line that includes ex-Communist countries. The most recent map shows little divergence here: even though there is less emphasis on survival values in both countries, they are still very close to each other.

Figure 1: Cultural map of the world

Source: World Values Survey.

To explain the position of Russia and Ukraine, we need to go beyond Inglehart’s earlier modernisation theory, in which he argued that under the influence of material wealth, societies gradually move towards more liberal and secular values. He added to this theory that despite the influence of economic change, the influence of the past (“path dependency”) still pervades. The shared past between Russia and Ukraine is therefore difficult to deny in value research.

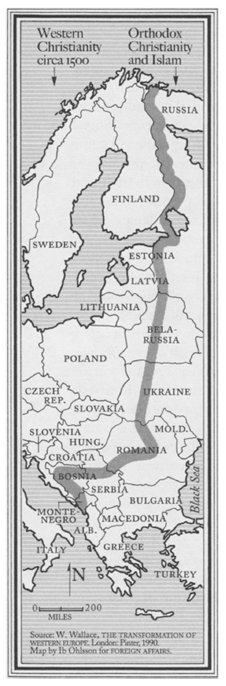

However, that shared past is not one and indivisible, as appears from the influential Clash of Civilizations thesis by Samuel Huntington. He claims that political conflict will increasingly run along the dividing lines of ‘civilisations’, he also discusses the important dividing line that traverses the European continent, a line that separates Western Christianity from Orthodox Christianity and Islam. This dividing line begins in Northern Europe, where it forms the border between Finland and Russia, and ends in the Balkans, but also runs through Belarus and Ukraine.

Figure 2: ‘Dividing line’ between European civilisations

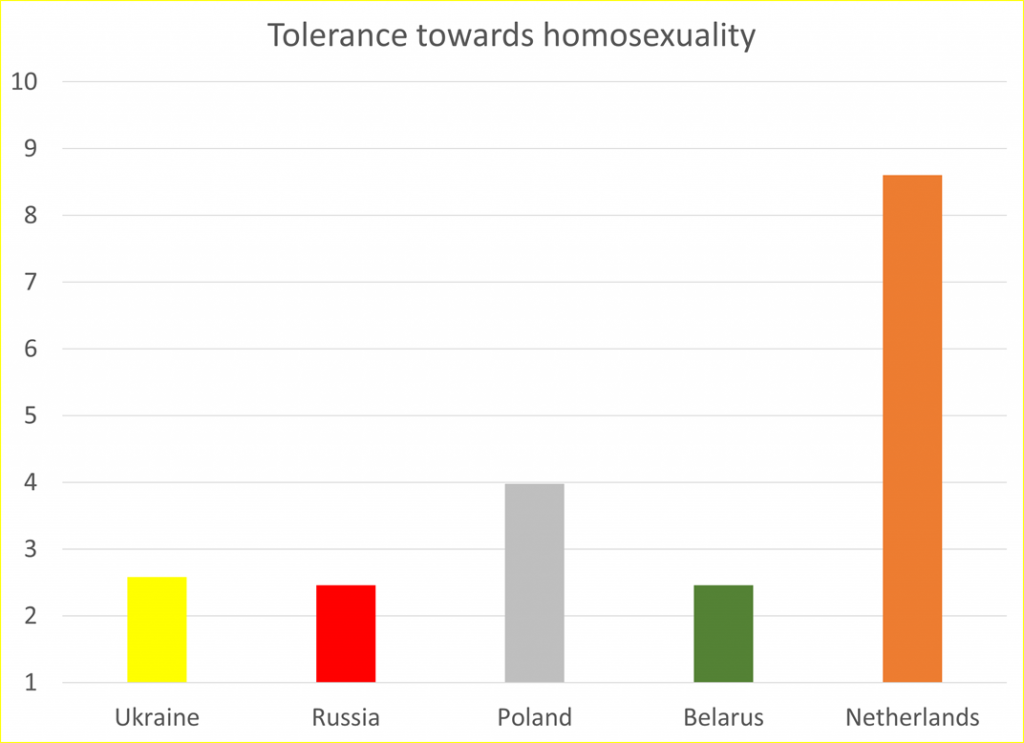

To find out to what extent Ukraine is more likely to reflect Russian values than the values of its largest European neighbour – Poland – I use the most recent data from the European Values Study (2017).[i] For reasons of clarity, I first look at so-called ‘self-expression values’, in particular views on homosexuality. While we see on the graph that tolerance in the Netherlands is quite high (8.6 on a scale of 1-10), Ukraine (2.6) does not differ in this respect from Russia or Belarus (both 2.5). Even if the tolerance in Poland is not particularly high (4.0), there is a clear difference with Ukraine.[ii]

Figure 3: Tolerance towards homosexuality in selected countries

Source: Compiled by the author using European Values Study data.

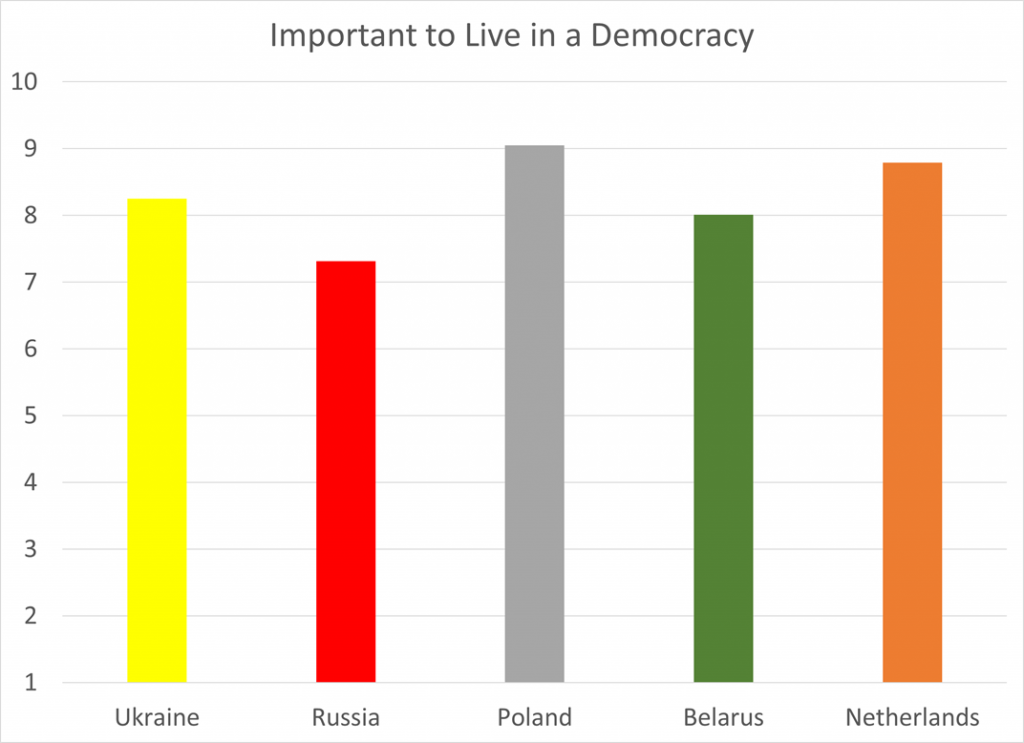

The story becomes more interesting if we examine some political views. Although on average it is considered important in all countries to live in a democracy, this aspiration is least present in Russia (7.3 on a scale of 1-10). In Ukraine (8.25), which is closer to European attitudes (see the 9.1 in Poland), there are very pronounced European aspirations; aspirations are lower in the Netherlands (8.8) than in Poland.

Figure 4: Reported importance of democracy in selected European countries

Source: Compiled by the author using European Values Study data.

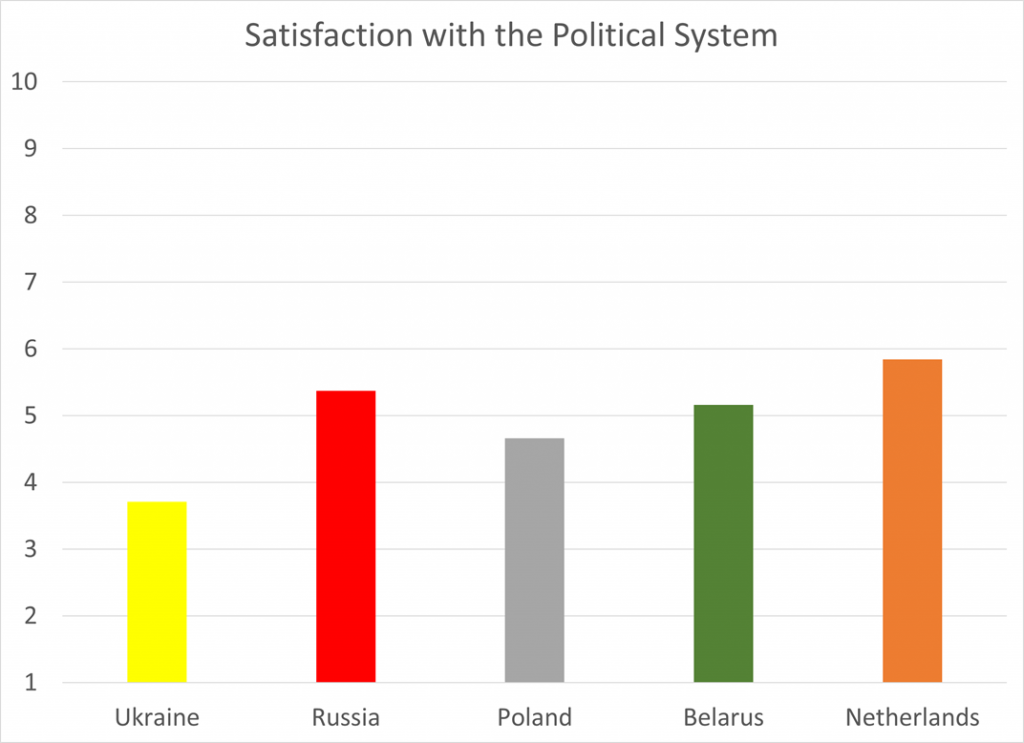

But when we compare the satisfaction with the functioning of the political system, Ukraine scores very low: with a satisfaction of 3.7 on a scale of 1-10, it is significantly lower than that of its Polish neighbour (4.7) while satisfaction is higher in Russia (5.4) and the Netherlands (5.8). This is an interesting observation: while in Russia there are, by comparison, less high aspirations for a well-functioning democracy, Russians are relatively satisfied. In Ukraine, aspirations are higher, but satisfaction is lower. It is precisely this discrepancy that may call for deep reform, something President Zelensky was confronted with during his presidency.

Figure 5: Satisfaction with the political system in selected European countries

Source: Compiled by the author using European Values Study data.

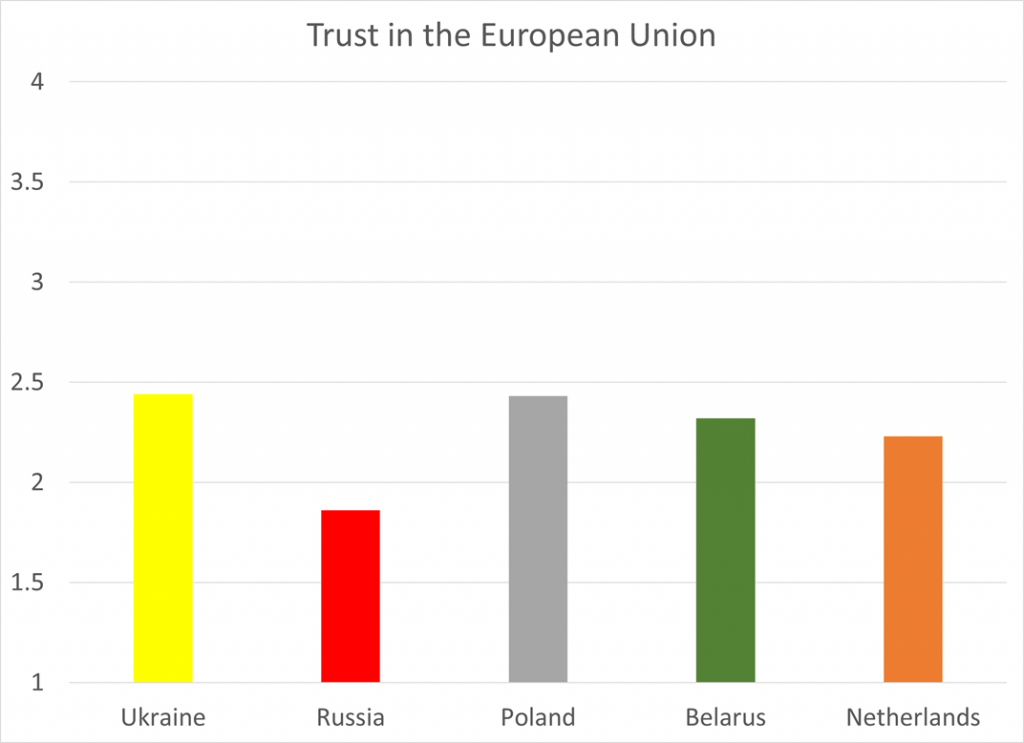

To what extent can Europe ‘buoy’ Ukraine? Here we see precisely that Ukraine, which is not a member of the EU, has relatively high confidence in the European Union (2.4 on a scale of 1-4). This puts the country at the same height as Poland (2.4) and Belarus (2.3), and even higher than the Netherlands (2.2). It leaves Russia far behind (1.9).

Figure 6: Trust in the European Union in selected European countries

Source: Compiled by the author using European Values Study data.

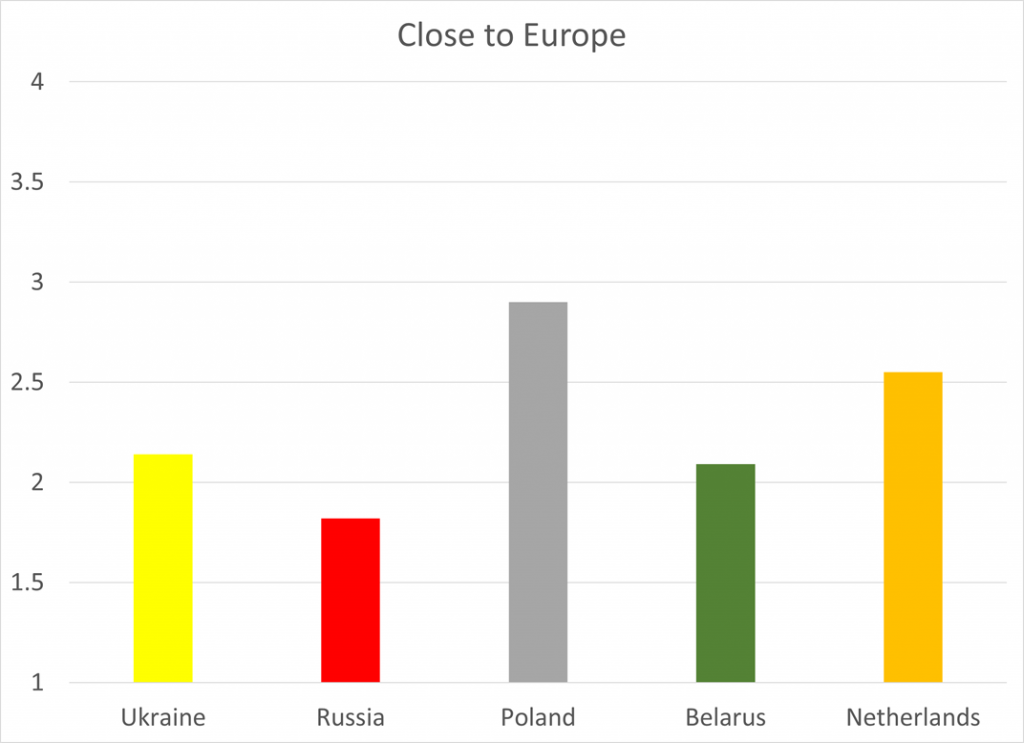

We also see that Ukraine (2.1 on a scale of 1-4) leaves Russia behind (1.8) with regard to the extent to which people feel connected to Europe. However, in Poland (2.9) and the Netherlands (2.6), the connection is even higher.

Figure 7: Reported ‘closeness to Europe’ in selected European countries

Source: Compiled by the author using European Values Study data.

When Ursula von der Leyen claims that Ukraine is “one of us” and should eventually join the European Union, economic, political, and humanitarian considerations seem to take the upper hand over cultural similarities and differences. Ukraine is no different from Russia in some crucial value dimensions, but since when have cultural similarities been an argument for a military invasion of an independent nation-state? On the other hand, politically in Ukraine, more than in Russia, there is a call for democracy, while the current system does not satisfy Ukrainians. Ukraine is looking at Europe to achieve this. And indeed, as Yuval Noah Harari points out, it’s easy to conquer a country, but that does not win their hearts.

European leaders may be apprehensive about expanding further to the East precisely because the discourse of successful right-wing populist parties in Eastern Europe conflicts with the core values of the European political project. But as Plamen Akaliyski’s research shows, European integration is not just limited to economic and political cooperation between countries, but also to values convergence: the longer a country is a member of the EU, the more it respects the values of the founding countries. Although this remains a slow process, incorporating Ukraine into a European political project could also cut ties with ‘Mother Russia’.

[i] The data set that was analysed is the integrated EVS-WVS data file (ZA7505), and can be downloaded via GESIS/Zacat. The weight coefficient was applied to correct for sample bias.

[ii] The European Values Study allows for more refined analyses at the regional level (NUTS1). Although there are some substantively relevant findings here, due to the limited scope of this blog, they are not further discussed.

Note: This article appeared earlier, in Dutch, on Sociale Vraagstukken. The article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Together with Loek Halman, Inge Sieben, and Marga van Zundert, Tim Reeskens will present the new “Atlas of European Values: Changes and Continuity in Turbulent Times” (Open Press TiU) on 9 May at the European Values conference. Featured image credit: Yaroslav Romanenko on Unsplash

Quite interesting. I found the following. Despite the political inclination to the West, ex-Communist nations, including Ukraine, are culturally closer to Russia. Japan is much closer to the West, rather than Asia.

But what are self-expression values and survival values?

So Greece us culturally not part of Western Europe?!

NB. Belarus is closer to Lithuania than Russia.