How has the Covid-19 pandemic affected trust in politics among citizens? Drawing on a unique survey of young people in Germany, France, Italy, and Spain, Anna Bottasso, Gianluca Cerruti and Maurizio Conti demonstrate that political trust during the pandemic has been influenced by previous perceptions about the efficiency of local institutions. Regions that were perceived to have high quality institutions experienced an increase of 9% in political trust levels compared to regions with low quality institutions.

Recent research has highlighted that major economic, political, military, climatic or health shocks might have important and persistent effects on contemporary economic outcomes. Moreover, these shocks might lead to institutional changes that can affect the evolution of cultural traits. One of the most important cultural traits is political trust – something that varies significantly between countries and across regions. Indeed, trust levels are deep-rooted in local communities since they are, to a great extent, the by-product of history and because they move slowly over time.

However, research suggests that alongside historical events, contemporary shocks in the economic, political and social domains can also significantly influence trust levels. Previous studies have found that trust in political institutions (both political parties and government) can be negatively affected by large economic shocks (e.g. a recession) and that high levels of political trust are crucial to prevent the rise of populist parties and anti-system movements. Political trust is therefore a key ingredient for the functioning and the preservation of democracy and the pursuit of economic growth.

Despite these findings being widely acknowledged, little research has been done on how the Covid-19 pandemic has affected trust in political institutions. This issue is particularly important because previous work has shown that individuals exposed to pandemic shocks during their youth tend to exhibit lower levels of trust in political institutions in later life. Moreover, this effect is largely driven by individuals who experienced a pandemic under a weak government.

In contrast, some political scientists have found evidence for the ‘rally round the flag’ effect, according to which people tend to show higher levels of trust in political parties and government during crises such as wars or pandemics. In this framework, a deterioration in political trust would occur only if the severe negative effects triggered by the crisis counterbalance the tendency to support political parties and the government through an emergency.

In a recent study, we analyse how the Covid-19 pandemic has affected the short-term level of trust in political institutions for a representative repeated cross-section of young adults (aged between 18 and 35) surveyed in the four largest EU countries – Germany, France, Italy and Spain – in 2019 and 2020. More specifically, we investigate whether the quality of institutions – as perceived by citizens – acts as a mediating factor in the impact of the pandemic on individuals’ trust in political institutions.

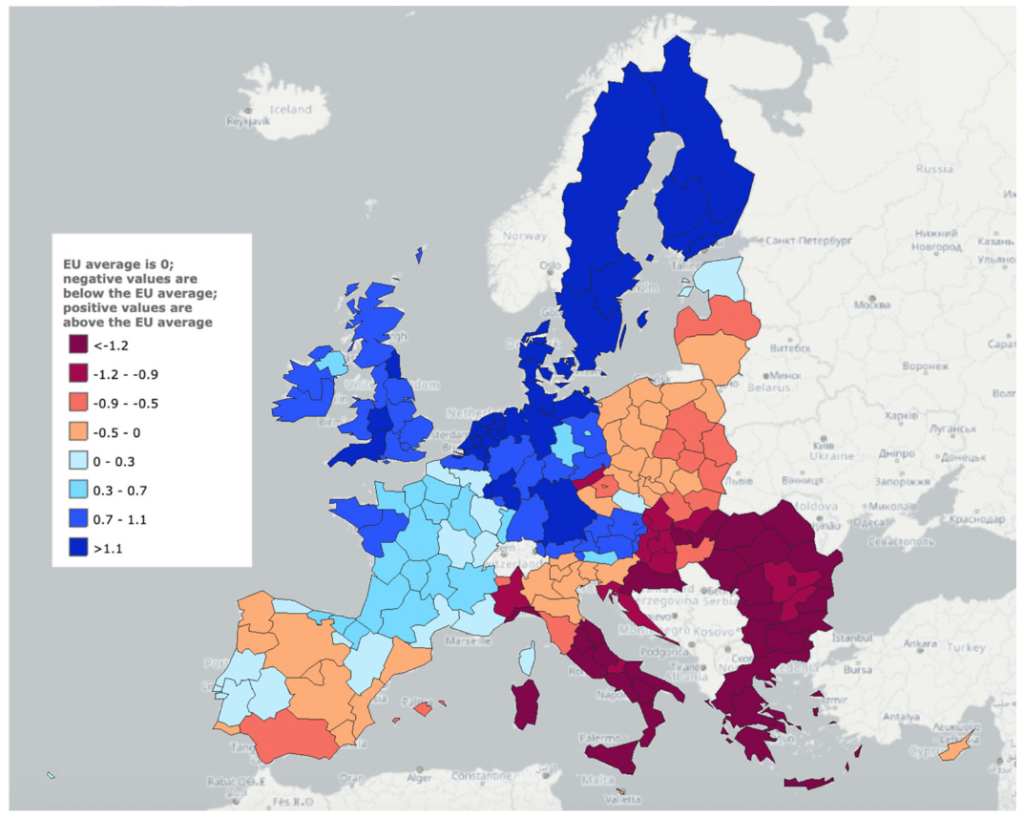

We focus on the quality of local institutions given that in Germany, Spain and Italy (and to a lesser extent France) regional governments have important degrees of autonomy in some domains, like the management of public health emergencies. Although we know that national governments made the most important decisions during the pandemic in most European states, we believe that focusing on the quality of institutions at the local level is appropriate given the significant differences that have been observed among regions within countries in the provision of both national and local public services. We use the European Quality of Government Index (EQI) to capture the quality of institutions, which is the only indicator available at regional level on a European scale.

Figure 1: Map of European Quality of Government Index scores in European regions (2017)

Note: The map shows scores from the European Quality of Government Index in NUTS-2 regions. A high score indicates a high level of quality while a low score indicates the opposite. Data from European Commission.

We test whether individuals living in regions with high scores in the EQI index witnessed a significant change in political trust during the pandemic. To do this, we apply a variant of the difference-in-differences approach, which allows us to measure whether the effect of the pandemic on political trust has been relatively stronger in regions characterised by high scores in the EQI index.

We control for regional fixed effects at the most granular level of disaggregation (NUTS-3), as well as for a rich set of individual characteristics. Moreover, to better identify the mediating role played by government quality, we also consider how the effect on political trust of regional characteristics (geographic, socio-economic, health-related and demographic) changed with the development of the pandemic, besides controlling for time varying characteristics like country-specific mobility stringency indices or the regional excess mortality rate, as well as various indicators related to fears of recession.

Our results suggest that in the first quarter of 2020, the probability that an individual reported trust in political institutions increased by about 9% in regions with high institutional quality (75th percentile), compared to regions with low institutional quality (25th percentile). We also find that this effect is largely associated with citizens’ previous perceptions about corruption and the impartiality of institutions, as opposed to the actual quality of public services. Moreover, our study suggests that the relative decline in political trust of individuals living in areas with low quality institutions since the outbreak of Covid-19 is stronger in the case of those aged 18 to 25. These results are robust to a large battery of robustness checks.

Our findings can be interpreted in two ways. On the one hand, we might assume that higher quality local governments have better addressed the pandemic. On the other hand, since the EQI relies heavily on subjective perceptions, it is possible that individuals living in regions with higher perceived quality of government simply did not blame politicians for the consequences of the pandemic.

What emerges from our analysis is that the perceived quality of institutions played a key role in preventing a collapse in people’s trust in politics during the pandemic, at least in the short term. However, the relative decline of trust in political institutions observed for individuals living in regions with low quality governments may be a cause for concern, particularly given the previous research showing that weak governance during a pandemic can have a lasting impact on political trust levels among young people.

Our findings suggest the need to better monitor young people’s attitudes toward political institutions, particularly in regions with low quality of government. There is a clear risk of a vicious circle developing, with the negative shock from the pandemic further bringing down trust levels in those areas that already had issues with political trust. This, in turn, might lead to even more pessimistic views about political institutions. While physicians are concerned with the problem of ‘long covid’ as a medical condition, we believe that economists and political scientists should be concerned with a different type of ‘long covid’ associated with a decline in political trust that could potentially trigger further waves of populism in the future.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the Journal of Regional Science

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Gabriella Clare Marino on Unsplash