Over the past three decades, white working-class men in Western democracies feel they have lost social standing, write Noam Gidron and Peter A Hall. People who lack social status tend to be politically alienated and to gravitate towards right-wing populist parties. While Donald Trump appealed directly to these people during his presidential campaign, the perceived fall in status probably also increased support for Brexit in the UK. Redistributive policies will not be enough to stem this trend, because social status also depends on providing people with decent, well-paid jobs. But on a symbolic level, politicians also need to ensure that the less-educated feel they have a place and a voice in society.

Over the past three decades, white working-class men in Western democracies feel they have lost social standing, write Noam Gidron and Peter A Hall. People who lack social status tend to be politically alienated and to gravitate towards right-wing populist parties. While Donald Trump appealed directly to these people during his presidential campaign, the perceived fall in status probably also increased support for Brexit in the UK. Redistributive policies will not be enough to stem this trend, because social status also depends on providing people with decent, well-paid jobs. But on a symbolic level, politicians also need to ensure that the less-educated feel they have a place and a voice in society.

The Brexit referendum exposed deep political divisions within British society, and more than a year after that vote, those divisions show no signs of disappearing. Although the Leave campaign was carried to victory on the back of a broad coalition, one of its striking features was high levels of support for Brexit among white working-class men without a college education – a group that is also especially likely to vote for right-populist candidates in other countries. Why is there such strong support for right-populist causes and candidates among the white working class?

In both the media and scholarly commentary, discussion of this issue has been dominated by a debate about whether rising support for right populism is rooted in economic or cultural developments. On the one hand, some interpret support for right-wing populism as a rejection of multicultural discourse and post-materialist values. On the other hand, other analysts emphasise the degree to which support for populism is linked with economic distress and insecurity. With regard to Brexit, the former present evidence that those in the Leave camp were driven by perceived cultural threats to national identity, while the latter point out that regional unemployment was strongly associated with support for leaving the European Union.

Photo: Alejandro Erickson via a CC-BY-NC-SA 2.0 licence

However, we think that asking whether economic or cultural developments were more important to such outcomes is to ask the wrong question. There are good reasons for believing that economic and cultural developments have operated together to increase support for populism. The more important question, then, is not whether populism is driven by either economic or cultural factors—but rather how economic and cultural forces might combine to shape the populist politics of our time.

In a recent article published in the British Journal of Sociology, we propose that one way to understand how economic and cultural factors interact is to see support for Brexit and right populism more generally among the white working class as a reflection of status anxiety rooted in broader processes of social marginalisation. We support this argument using survey data collected across Western democracies between 1987 and 2014 as part of the International Social Survey Programme.

Our focus is on subjective social status, namely, a person’s sense that they are accorded the social respect or status associated with full membership in society. There are good reasons for thinking that economic and cultural developments have combined to depress the subjective social status of white working-class men. Since social status is typically conferred by levels of income and the quality of one’s occupation, shifting patterns of employment that have eliminated well-paid, medium-skill jobs and forced many men into more precarious positions may well have undercut their own sense of where they stand in society. At the same time, shifts in cultural frameworks, marked by an increasing emphasis in mainstream discourse on racial and gender equality, may have threatened the subjective social status of any who may have relied on the notion that they were white or male to underpin their own sense of social standing.

Thus, economic and cultural developments happening independently of each other may have combined to have additive effects on the social status of some groups. But there may also be interactive effects at work here. For instance, movement toward a knowledge economy has increased the demand for highly-skilled workers and the wage premium to college degrees, putting people without such a degree at an economic disadvantage. But, as more people acquire such degrees, the social esteem accorded those who lack one may well have fallen. In this case, a particular set of economic developments sets in motion changes in cultural frameworks that multiply the effects.

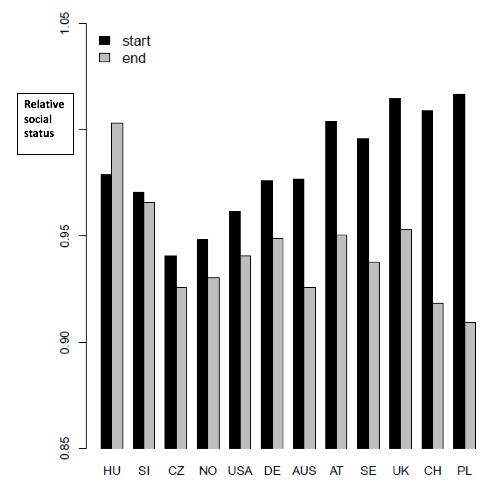

If these conjectures are correct, we should expect to see some decline in the subjective social status of men without a college education over the past few decades, and that is what we find in this study of twelve developed democracies. We measured social status using a question that asked survey respondents to place themselves on a social ladder reflecting whether they were closer to the top or bottom of society. In almost every country within our sample, men without a college education reported lower levels of relative social status in 2014 than they did two or three decades before. These declines were modest but remarkably consistent.

Figure: The relative social status of men without a college education circa 1990 and 2014

Note: Start period for Germany, Sweden, Norway, the Czech Republic and Slovenia is 1992; end period for UK and Hungary is 2009. Otherwise start period is 1987 and end period is 2014. Source: ISSP Surveys; Gidron and Hall 2017.

Is this decline in subjective social status reflected in support for the populist right? We think there are good reasons to believe it is. Previous work in sociology has demonstrated that people care just as much about social status as they do about money. Thus, working-class voters who feel their social status is eroding may well turn against the mainstream parties who have presided over that; and they may well be inclined toward candidates who promise to restore that status, as many on the populist right do. Donald Trump appealed directly to such concerns, for instance, with language evident in this campaign speech:

While my opponent slanders you as deplorable and irredeemable, I call you hardworking American patriots who love your country and want a better future for all of our people. You are mothers and fathers, soldiers and sailors, carpenters and welders […] You are Americans and you are entitled to leadership that honors you, cherishes you, and defends you. Every American is entitled to be treated with dignity and respect in our country.

In line with this, we find that, across the developed democracies, lower levels of subjective social status are strongly associated with voting for right-wing populist parties. Moreover, people who express lower levels of social standing also express higher levels of political alienation (reflected in the belief that one has to be corrupt in order to succeed in life) and deeper opposition to immigration – an attitude important to the populist right and the Leave campaign. We think there is real promise in approaching support for the populist right as a problem of social integration, born of economic and cultural developments that have led some groups of people to feel increasingly marginal to mainstream society.

These findings also carry implications for how the populist challenge can be addressed. Much of the current discussion is focused on providing better material compensation for the ‘losers’ of globalisation, often in the form of more generous programs of redistribution. Yet our research suggests that support for populism is not motivated primarily by demands for more redistribution but by more fundamental concerns about social recognition and respect. Since social recognition is closely-linked to having a decent job, addressing those concerns will require efforts to create such jobs and to make existing jobs more decent. But it will also require efforts on the symbolic plane of political discourse to ensure that people in all walks of life are recognised as valued members of society.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article originally appeared at our sister site, LSE Brexit. It gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Noam Gidron – Princeton University

Noam Gidron – Princeton University

Noam Gidron is a fellow at the Niehaus Center for Globalization and Governance at Princeton University. Beginning in 2018, he will join the faculty of the Department of Political Science and the Joint Program in Politics, Philosophy and Economics (PPE) at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Peter A Hall – Harvard University

Peter A Hall – Harvard University

Peter A Hall is Krupp Foundation Professor of European Studies in the Department of Government, Harvard University, and at the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies.

I think this analysis doesn’t address the issue fully. Older working class people may have voted for Brexit but younger working class people were so alienated they didn’t vote at all; hence the apparent difference in percentage outcomes between younger and older voters.

I think you need to dig a little deeper too. I have working class parents but am educated to post-graduate level. I voted with the working class.

Central to the White Working Class exclusion has been their educational underachievement, something I tried to draw attention to but with little success. So the problem has continued with boys and girls leaving school with few or no qualifications and going onto live a life of exclusion as adults.

https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200809/cmhansrd/cm090519/halltext/90519h0011.htm

The male working class had its ” golden years” of 1950 to 1970 in the Western world. This was based on them receiving large crumbs from the western capitalist system that was based on exploitation of third world oil and other raw materials; combined with a western monopoly of technology. The rich in the West preferred a society where the wealth was partly shared and they didn’t have to live behind barb wire and guard dogs.

Globalisation has brought the benefits of raw materials and technology beyond the West. The western rich have not suffered but the white male manual worker has. Four hundred million chinese now have western style living standards. Should ( and could) that have been prevented in order to preserve high living standards in Detroit amongst its car manufacturer workers?

I note that the ” Luddites” were condemned for their wish to preserve a comfortable existence for themselves. Should have soceity helped the ” Luddites ” to adapt to technological change? One thing is clear, protectionist policies, whether internal to a state or external, do not bring long term economic sucess

There is no possibility of creating those “decent jobs.” Production does not require them in significant numbers. Jobs are increasingly expert or low skilled, i.e. the mass of decent, middle ground jobs has gone forever. This has to be faced rather than pretending it is still the 20th century. This may explain: https://colummccaffery.wordpress.com/2017/12/17/full-employment-in-this-century-will-be-different-as-work-befitting-educated-skilled-workers-grows-scarce/

You seem to forget that working class women in the UK get an even worse deal than working class men. But women are more socially conformist than men and the media was literally saturated with insults about people who might vote Brexit: Bigots, racist, poor, stupid, undecuted blah blah blah..

You would do well to revisit the Referendum. Project Fear is now known to have been a total fabrication. The referendum hasn’t affected GDP but the productivity decline since 2008 is having a deadly effect. Here is an article that summarizes the benefits of Remaining in the EU for the ordinary people of the UK: http://pol-check.blogspot.com/2017/12/the-pros-and-cons-of-remaining-in-eu.html . It is much worse than Brexit.

Real wages have fallen since the referendum and growth for 2017 was well below what was predicted prior to the referendum (despite favourable external conditions). There have been negative consequences from the vote in the short-term and obsessing about “project fear” really doesn’t achieve anything. It’s a classic campaigning tactic used by Leave activists to focus on fostering outrage about people like George Osborne lying rather than to focus on the broader picture of what Brexit is actually doing to our economy or will do to it in the future. The referendum result damaged our living standards in the short-term and it will damage them even further when Brexit is actually implemented. What George Osborne and David Cameron said years ago is irrelevant to that picture.

And we can all point out that the Leave campaign also lied consistently during the campaign. They willfully conflated the refugee crisis with EU membership. They lied about Turkey being ready to join the EU and that the UK couldn’t veto its accession. They lied about the money we sent to Brussels. They lied about the very basics of how the EU works, consistently hammering a line about the Commission having the power to dictate laws, when everyone knows that isn’t how it works. They claimed we’d be forced to join an EU army if we’d stayed in, which remains nonsense (your link contains similar implausible claims about future integration – all of which fit the label of “project fear” far better than the many reasoned economic analyses which are routinely derided by leavers). The list goes on…

The one point I will agree with you on is that working class women are marginalised more than men in British society. The point about women only voting for Remain because they couldn’t see through anti-Leaver insults is largely baseless, however. You could just as easily point out that British newspapers were overwhelmingly in favour of Brexit, that there was a climate of hysteria built up over the issue (which tragically spilled over into outright violence in the case of Jo Cox), and that for every Leave voter branded a “racist” there will be a Remain voter branded a “traitor” by someone else. The implicit argument that women simply aren’t as free-thinking as men and were duped into voting Remain is about as crude as it gets I’m afraid.

UK productivity has been static for a decade so the variations in UK GDP over the past decade are largely explained by variations in the number of workers – see http://pol-check.blogspot.com/2017/11/why-is-uk-losing-productivity.html. There is no obvious discontinuity in GDP growth due to the Referendum, its business as usual. Sadly “business as usual” means continuing with our low productivity economy (check out the link above which explains why the EU is deeply implicated in this low productivity).

The bias of the media is as follows. In the case of the print media, The Sun, Daily Mail, Daily Express were pro-Brexit and the Mirror, Guardian, Independent, Times, Financial Times were Remain (with Telegraph vaguely Brexitish). British newspapers were definitely not “overwhelmingly in favour of Brexit”. In the case of the broadcast media, which is far more pervasive, all TV and radio stations were Remain. There is obviously no case for maintaining that the media were mostly in favour of Brexit, in fact, given the broadcast media were uniformly pro Remain it must be concluded that media was a pro Remain factor.

I draw your attention to the title of your article which has the words “white working class men” so is inherently about gender. The reason I raised the point about working class women was that, as you say, they are marginalized BUT they did not vote for Brexit as much as working class men. This shows that voting Brexit does not necessarily indicate marginalization – marginalized women (working class or not) voted Remain. If you want to fully understand voting patterns you will need to understand that there are indeed gender differences despite our desire that these should be abolished. Conformity is a factor where women outscore men so the entirely pro-Remain broadcasters, major political parties and educational establishments should have had a major influence on women.

That the people who are most directly exposed to the vicissitudes of the economy, the working classes, voted for Brexit should lead economists to ask what is going wrong with the economy and why did the working class link this to the EU? The article at the beginning of this comment answers much of this question. Have empathy for people who budget from week to week so that you can sympathize with their predicament rather than regarding them all as MP killing maniacs.

Just because mobile upper middle class academics did not get the referendum result that they desired doesn’t mean that that it is reasonable to write down a list of all the things that upper middle class academics most hate and pin this on the people who opposed their will. That is just spiteful and, yes, a form of upper middle class popularism.