Do Europeans perceive European integration as a threat to their welfare state or as an opportunity? Drawing on comparative survey data, Sharon Baute explains how national and supranational institutions simultaneously shape citizens’ expectations about social protection in the EU.

The President of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, has expressed her ambition to strengthen the social dimension of the European Union through the European Pillar of Social Rights, which aims to deliver new and more effective rights for citizens. However, while promoting social rights in all member states is an explicit policy objective of the EU, the relationship between European integration and the welfare state is less than clear cut.

Two contrasting perspectives dominate the political and academic debate on the relationship between European integration and the welfare state. The first perspective, known as the race to the bottom thesis, presumes the integration process will result in welfare spending being reduced to the lowest common denominator. In contrast, the upward convergence thesis suggests that European integration supports and strengthens the capacities of national welfare states.

But which of these perspectives do European citizens subscribe to? This is a nontrivial question because welfare related concerns are a distinct source of Euroscepticism. Hence, for the political viability of the European Union, the perspective of public opinion on this matter is of major importance. Accurate knowledge about citizens’ perceptions will help us to better understand mass Euroscepticism and yield deeper insights about the obstacles that inhibit the development of a more ‘Social Europe’.

Survey evidence

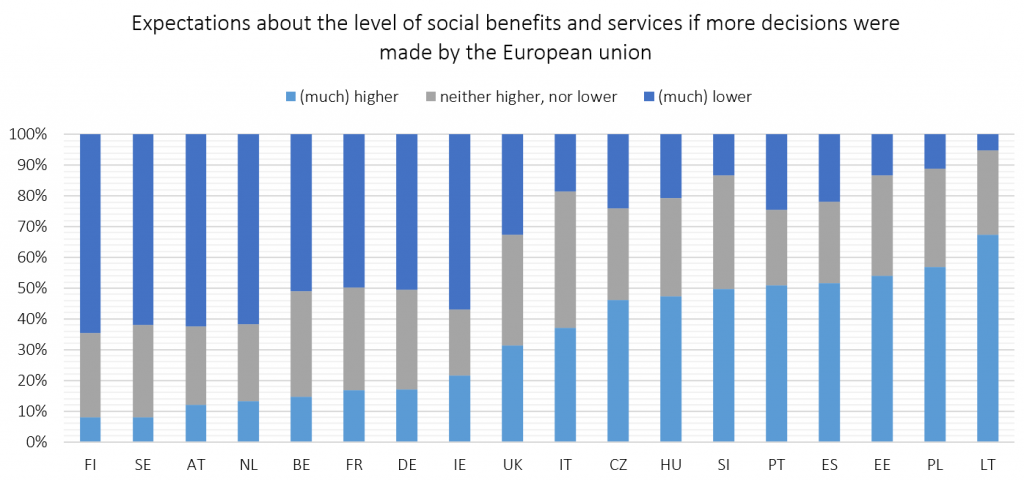

In a recent study, I investigate citizen expectations about whether a shift toward more EU decision-making will affect the level of social protection in their country using data from the European Social Survey (ESS8) ‘Welfare Attitudes Module’, covering 18 EU member states. Respondents were asked whether they think the level of social benefits and services provided in their country would become higher or lower if more decisions were made by the European Union.

Figure 1 shows the average expectations for each country, which are clearly divided along a geographical North-South and East-West line in Europe. Whether citizens believe in the ‘race to the bottom’ or the ‘upward convergence’ thesis strongly depends on where they live; Northern and Western Europeans tend to believe the former, whereas Eastern and Southern Europeans are more likely to believe the latter.

Figure 1: Citizens’ expectations about the impact of European integration on their welfare state, by country

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper in Social Policy & Administration.

How can these regional differences be explained? An important role can be attributed to institutions. Yet, since social policy has gradually become embedded in the multilevel governance architecture of the European Union, social protection is no longer an exclusively national affair. Therefore, it is important to consider both national and EU institutions.

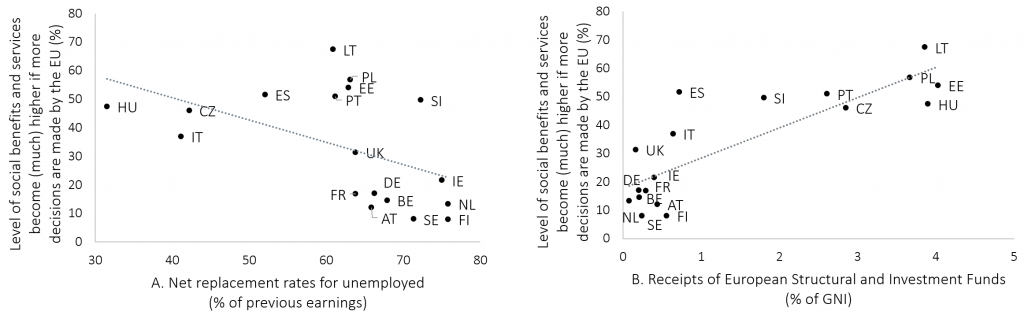

On the one hand, citizens perceive the process of European integration through a national lens, thus assessing the added value of the EU against what they currently have at home. This is illustrated in Figure 2a, showing that in Northern and Western European countries, where unemployment benefits are more generous, citizens are more likely to view the EU as a political actor that will erode social protection.

This suggests that citizens are aware that European integration could constrain the ability of national governments to sustain generous systems of social protection through its impact on both spending and revenue. Consequently, many people in North and West Europe may feel that the European Union does not devote sufficient attention to social developments in their country. Hence, in countries where welfare provision is generous, citizens are more likely to believe that further European integration will initiate a race to the bottom in social standards and provisions.

Figure 2: Impact of the generosity of unemployment benefits and the receipt of EU funds on perceptions about the EU’s effect on social security levels

Note: The figure shows country means for expectations about the EU’s impact on social security levels by (a) net replacement rates for long-term unemployment, and (b) receipt of European Structural and Investment Funds. Figure 2a suggests that citizens of countries with more generous unemployment benefits are more likely to think European integration will reduce social benefits and services. Figure 2b suggests that citizens of countries that receive lower levels of European Structural and Investment Funds are also more likely to think European integration will reduce social benefits and services.

On the other hand, EU institutions also matter for how citizens perceive the link between European integration and their welfare state. In countries that receive more resources from the EU spending programmes (relative to their GNI), citizens have far more optimistic expectations. This is illustrated in Figure 2b, showing that the upward convergence thesis prevails more strongly in those countries receiving more generous funding from the European Structural and Investment Funds, which are multi-annual programmes to support strategic long-term goals.

The redistributive component of EU social policy by means of funds that finance welfare reforms and social investment have thus a positive impact on social policy aspirations in Eastern and Southern Europe. These results suggest the existence of a policy feedback effect of supranational welfare policy on citizens’ thinking, whereby EU-level spending programmes nurture positive expectations about the future impact of EU decision-making on social protection levels.

EU governance is thus influencing what people believe, the way they see themselves (as well as other Europeans) and how they understand EU politics. This indicates that regional inequalities – relating to both national and supranational institutions – seem to drive visions apart on whether European integration poses a threat to the welfare state or offers opportunities.

Reconciling diverging expectations about social protection

The geographical divide in public expectations stands in sharp contrast to the EU’s renewed ambition to strengthen its social dimension through the European Pillar of Social Rights. Against this policy background, survey evidence points to a large number of people who are concerned that ‘more Europe’ will not result in a stronger welfare state. This shows the complexity of social policymaking in multilevel governance regimes.

It will be a major challenge for the EU to simultaneously meet the social concerns of these citizens – who are concentrated in the most developed welfare states – while giving effect to the high social aspirations in less-developed welfare states. The EU will need to prove and convince citizens in the most developed welfare states that ‘more Europe’ does not trigger a race to the bottom in social standards.

One way of doing this could be through building stronger trust in EU institutions. Citizens’ expectations about the EU-welfare nexus are not exclusively driven by institutions themselves but also by the perceptions citizens have of institutions. When citizens have higher levels of trust in EU institutions, this boosts their confidence in the upward convergence thesis.

This gives leeway to create more optimistic expectations in Northern and Western Europe, which, with their relatively generous welfare provisions in combination with being donor countries to the EU budget, might seem doomed to expect nothing but a race to the bottom from further European integration. Trust in the EU’s institutions therefore constitutes an important resource for policymakers at a time when the European project is being challenged by populist movements.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper in Social Policy & Administration

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council