There have been calls to strengthen the EU’s common foreign and security policy as a response to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. But what determines public support for these measures? Drawing on a new book, Kathleen E. Powers illustrates how European identities shape the views of citizens about EU security cooperation.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has elevated security concerns to the top of the European agenda. EU member states have provided aid to Ukraine and imposed large-scale sanctions against Russia with substantial support from their constituencies. This united front marks a substantial – and perhaps surprising – achievement for foreign policy cooperation. Now more than ever, the EU is exhibiting the commitment to common defence laid out in the 2009 Lisbon Treaty.

What drives public support for security cooperation? A common argument points to a collective European identification: if people feel that Germans, Italians, and Latvians belong to one European group, they trust each other and view their self-interest as aligned with the continent’s interest. If a threat to Latvia is a threat to Belgium, and citizens trust each other to resolve disputes without force within this group, they collectively cooperate against external threats.

In a new book, I argue that this simple story overlooks important nuance in how people form attachments to social groups. European residents can hold equally strong European commitments but maintain distinct ideas about what their membership in this group means. Some European identities drive support for cooperation, whereas others do not. Promoting a “European” identity without attention to its constituent parts risks undermining the goal of presenting a common front on the world stage.

Two dimensions of European identity

People categorise themselves and others into identity groups, sorting the world across national and transnational lines. To explain how these identities influence political attitudes, researchers must separate two dimensions: commitment and content.

Commitment denotes how strongly people identify with their group. Some people feel a stronger connection to Europe than others. Even when the United Kingdom had membership in the EU, for example, few Britons considered themselves European compared to their continental counterparts.

Extensive survey research has attempted to measure this European commitment. That effort, I argue, is incomplete because individuals hold markedly different ideas about what a “European” identity entails. People with stronger commitments adhere to the group’s norms, but these norms may not always facilitate transnational cooperation.

I stress that the second dimension – content – ultimately influences whether identification leads Europeans to trust each other in national security matters or instead reject deeper ties. People with stronger commitments adhere to a group’s norms, but these norms differ in whether they facilitate transnational cooperation.

When examining the content of the European identity, two common themes emerge – representing two sides of what it means to be “united in diversity.” Some people think that Europeans must maintain unity. Unity norms describe Europe as a transnational family – an extended kinship network with shared ancestry and religious traditions. A commitment to unity obligates Europeans to look out for their figurative “brothers and sisters,” but not fellow EU residents perceived as lacking the required historic or cultural ties.

Others view the European identity as embracing equality. These norms stress respect for EU laws, general European norms, and democratic participation. Conforming with the group requires treating all fellow Europeans fairly and as co-equals. Through this commitment to fairness and reciprocity, “we” Europeans can trust each other to share in our common defence.

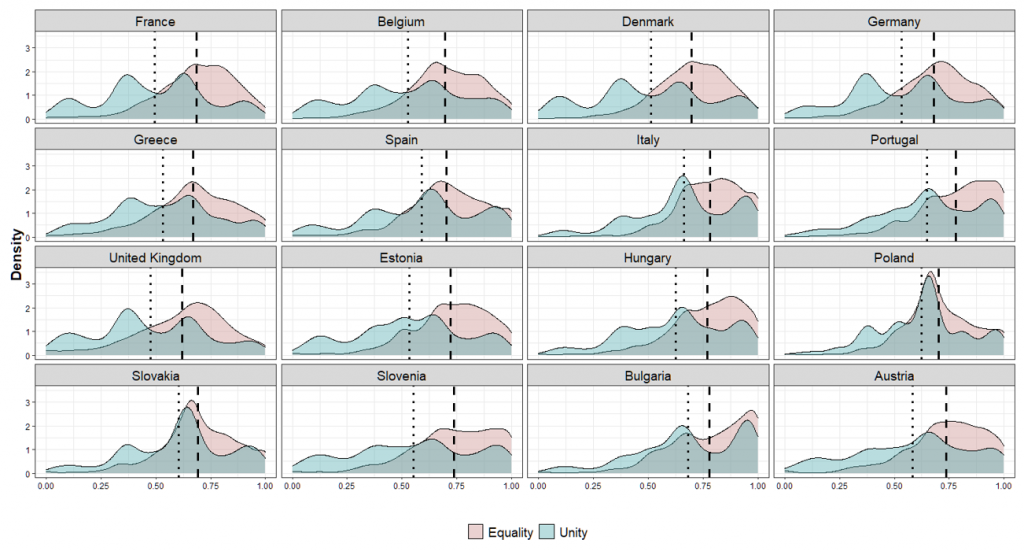

My analyses of 2007 and 2009 IntUne survey data show meaningful variation in public commitments along these two metrics: unity and equality. The figure below illustrates the proportion of respondents in each EU member state who think that being European means having European ancestry and practicing Christianity (unity) compared to respondents who think that European identity entails exercising citizens’ rights, feeling European, respecting European law, speaking any European language, and participating in European cultural traditions (equality).

Figure: Conceptions of what being European means in EU member states

Note: The values 0.00 to 1.00 along the x-axis indicate the extent to which respondents rated ‘equality’ and ‘unity’ important for ‘being European’. Participants rated 8 characteristics on a scale from `not at all important’ to `very important’ and I transformed these scores into latent unity and equality scales using factor analysis, a statistical technique for distilling a smaller number of core constructs from several survey questions. For instance, a respondent with a value of 1.00 for ‘equality’ rates each equality item very important to European identity. The charts illustrate the proportion of respondents in each country (density) that held each value. In Bulgaria, for example, the chart shows that a large proportion of respondents had high values for the ‘equality’ conception, indicating that many citizens in Bulgaria think that European identity entails ‘exercising citizens’ rights, feeling European, and respecting European law, speaking any European language, and participating in European cultural traditions’. The vertical lines show the average equality (dashed) and unity (dotted) scores in each country.

All told, Europeans disagree about which characteristics matter for group membership. Respondents endorsed equality at higher rates in each country – the pink distribution is skewed toward higher values – but unity clearly captures a common sentiment across countries.

Committing to equality drives support for security cooperation

This observation invites a follow-up question: do these differences in identity content matter for views about European security cooperation? I answer this question by using statistical analyses to test the relationship between these identity content measures and a question that asked respondents whether they support a single foreign policy for the European Union.

I find that the degree to which people commit to unity or equality explains substantial variation in their support for a collective European foreign policy. Compared to the scale minimum, respondents who view their “European” identity as a commitment to equality show increased support for a common foreign policy by 38 percentage points. This shift is significant, enough to swing someone from “somewhat against” a common foreign policy to “somewhat in favour.” By contrast, respondents who associated their European identity with traditional unity norms were less likely to endorse a common foreign policy.

These differences hold despite accounting for self-reported identification with Europe. Indeed, the degree of self-reported European identification alone explains much less about respondents’ support for a common EU foreign policy than their commitment to equality. These patterns hold across other important outcomes and in a large sample of political and business elites. A European identity defined by equality norms increases trust in fellow Europeans and support for a European army to supplement or replace national forces across samples.

What do these findings mean for the future for European security cooperation? Building and sustaining a European identity has been a perennial EU goal amid rising nationalism and external threats. But commitment alone may not prescribe cooperation, and the EU’s efforts to give meaning to European identity often adopt a little-bit-of-everything approach: The EU’s Committee on Culture and Education, for example, has been charged with both preserving European heritage (unity) and creating an inclusive society (equality). That, in turn, cultivates both strands of the European identity – a potentially counterproductive endeavour given their contrasting features.

As the EU integrates its newest members and faces mounting costs from its stand against Russia, elites hoping to foment support for a “real, true European army” might consider cultivating norms that facilitate equality and cooperation. Stressing a European identity alone risks backfiring.

For more information, see the author’s new book, Nationalisms in International Politics (Princeton University Press, 2022)

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council