When the British electorate voted in 2016 to leave the EU, it was already clear that the implications for UK social sciences and humanities researchers were likely to be greater than for other disciplines. Three years after the Brexit Withdrawal Agreement was signed on 24 January 2020, Linda Hantrais and Grace McConnell ask whether these fears have been realised, and explain how LSE, as the leading social science institution in the UK, is dealing with the uncertainties surrounding access to European research funding, networks, and collaborations.

Following the EU referendum, the UK research community was confident it would be granted at least associate status in the post-Brexit settlement. With the triggering of Article 50 in 2017, fears were aroused about the conditions for their future participation in EU-funded projects. These concerns intensified during the negotiations of the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA). They peaked as the UK moved into the implementation phase in January 2021.

UK scientists realised that, even as associate members of the Horizon research programmes, limitations would be imposed on their ability not only to participate in and lead EU projects but also to host researchers from EU member states. Concessions would be needed following the ending of freedom of movement. The income the UK received from EU funds would not be allowed to exceed their contribution to the EU Research and Innovation budget.

But little did the research community anticipate that access to associate status would be blocked for more than two years by political wrangles over the Northern Ireland Protocol. The burden of uncertainty and anxiety was most palpable in institutions that had come to rely heavily on EU funding and collaborations to underpin their international research profiles.

What UK social scientists stood to lose post-Brexit

When the first European framework programme (FP) was launched in 1984, social and human scientists had been the handmaiden to the natural sciences. The extension a decade later of the framework programmes by the introduction of a dedicated Targeted Socio-Economic Research (TSER) stream in FP4 opened up exciting new opportunities for social and human science researchers in Europe. These developments were further enhanced by the European Research Council’s (ERC) scheme, initiated in 2007, to support investigator-driven frontier research across all fields, based wholly on scientific excellence.

UK social scientists, supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC), had been centrally involved in negotiating the TSER and ERC programmes. They exploited the strong competitive advantage gained from their long experience of bidding for research council funds to apply for, and obtain, relatively large numbers of EU awards, while social and human science researchers in other member states grappled with the bureaucracy of the European funding system.

Analysis of comparative data from 2014 UK Research Excellence Framework panels showed that, since 2006, the volume of EU funding for social and human science projects had increased rapidly, bringing the EU contribution close to that received from the UK government, and to more than half the amount awarded by UK research councils.

EU statistics confirmed that, on the eve of the referendum in 2016, social and human science researchers in UK universities were consistently outperforming their counterparts in other member states, both in leading EU-funded Horizon 2020 (FP8) projects and in hosting ERC awards. Research had become an area of the EU budget where the UK was estimated to be receiving more from the EU pot than it was contributing.

Post-referendum trends in EU funding for UK social sciences and humanities

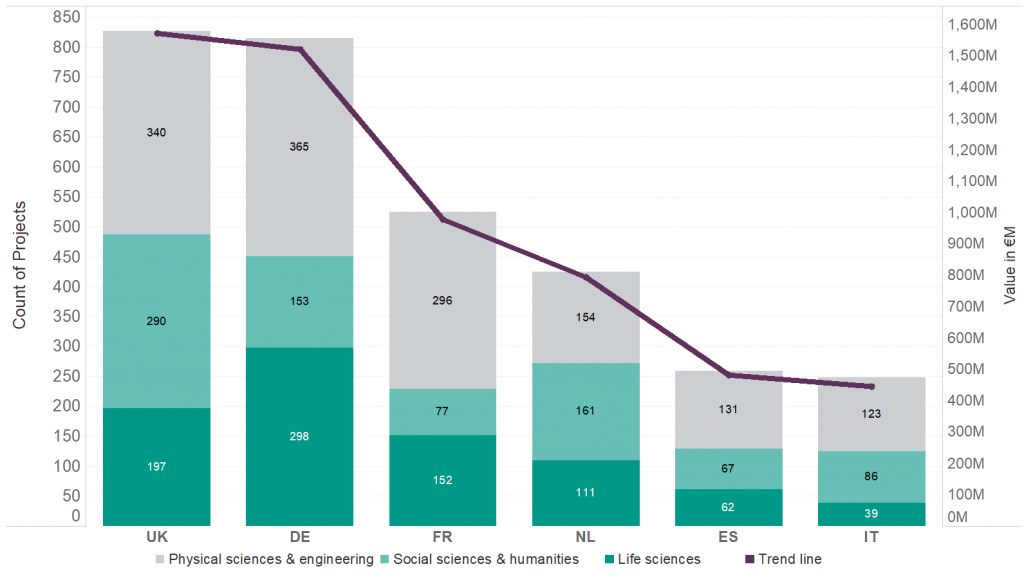

EU statistics for the period 2016−20 show that, while the Withdrawal Agreement was being negotiated, UK social sciences and humanities maintained their strong lead in terms of the number of award holders hosted and the amount of funding received from prestigious ERC grants (starting, advanced and consolidator grants). This trend applied both in relation to other member states and to life sciences (see Figure 1). Year-on-year, UK social sciences and humanities received almost twice the number of awards and the amount of funding obtained by the Netherlands and Germany, and considerably more than for the life sciences.

Figure 1: UK ERC number and value of awards 2016-2020

Source: European Research Council datahub.

In 2021, as TCA negotiations stalled due to the political situation over the Northern Ireland Protocol, the UK disappeared from the charts. It was replaced by Germany and the Netherlands for starting grants, by Germany for consolidator grants, and by Spain, Italy and Germany for advanced grants. However, in all these cases, the number of awards and levels of funding were much smaller than those previously achieved by the UK.

Pending confirmation of its associate status, the UK government offered guaranteed top-up funding for Horizon 2020 award holders who had begun their projects before the withdrawal date. This offer was subsequently extended to awards made after that date. In the confident expectation that the UK would be granted associate status, the UK Research Office Brussels office strongly urged UK researchers to continue applying for Horizon Europe awards. As for third country applicants, from 2021, proposals from UK researchers could still be evaluated in Brussels. But any projects accepted could no longer be badged as EU awards unless they were hosted by an EU27 member state and provided their own funding.

When, in November 2022, the association agreement had still not been signed, the UK government announced that it was implementing transitional measures for new UK-funded research and development programmes. This arrangement, delivered by UK Research and Innovation (UKRI), provided what could be seen as a less bureaucratic and more flexible alternative to EU funding. However, it raised fears in the research community about the extent to which these transitional funds might reduce the resources available for European collaborative projects.

The uncertainty generated by the delay meant that researchers were reluctant to spend time on applications for EU-funded awards knowing that they might not bear the EU imprimatur. EU partners were frustrated with the situation and unsure whether to include UK participants in their consortia. They were aware that, without EU recognition, UK team members might not be able to fulfil their commitments.

This demise was exacerbated by the progressive shift, both in the EU under Horizon Europe (FP9) and in the UK within its industrial strategy, towards funding support for multidisciplinary projects. The merger in 2018 of the UK research councils within the overarching structure of UKRI as the national funding agency for building capacity confirmed that science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) topics would be in the front line to deal with global societal challenges. Social science and humanities researchers risked being relegated to their earlier subservient role, where they had to compete against other disciplines, or join with them, while seeking out alternative sources of support.

Implications of Brexit for LSE research

Prior to the referendum, in company with the University of Oxford, UCL, the University of Cambridge and the University of Edinburgh, and despite its relatively small size, LSE was leading the charts for UK ERC social science and humanities award holders. Between 2008 and 2013, the proportion of EU funds (from framework programmes, EU charities and corporates) in all LSE research income had risen steadily from around 17% to 31.2%, whereas the proportions LSE received from UK research councils and the UK government had fallen. These trends were reflected in staffing levels at LSE between 2004−05 and 2014−15: UK research-only staff were overtaken by EU research-only staff as the largest ‘nationality group’.

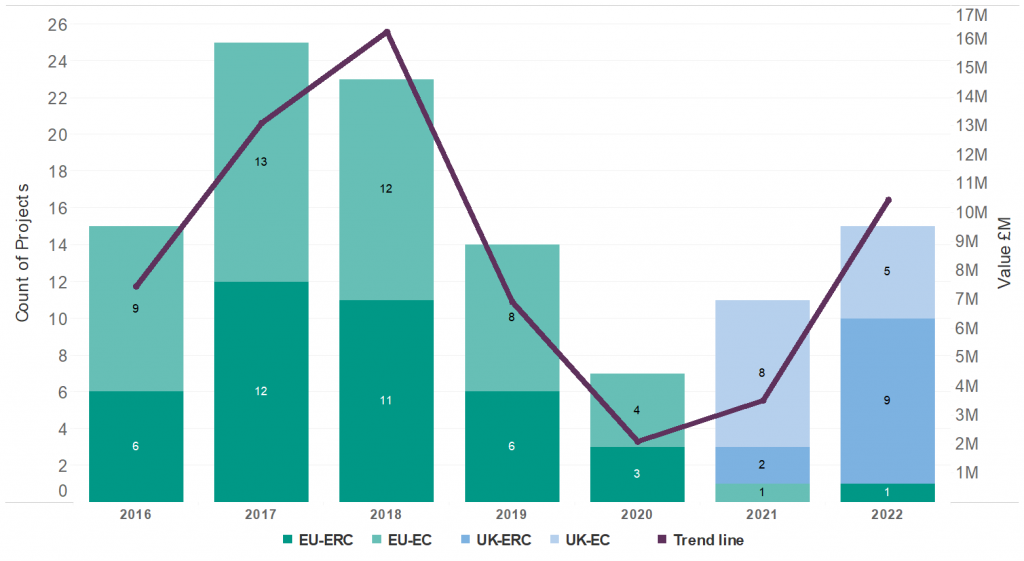

Having peaked in 2015, and following a dip in 2016, the total amount of research funding awarded to LSE from EU sources rose again to the pre-referendum level; it then fell to an all-time low in 2020 for EC and ERC awards, only to recover for EC funds in 2021 (see Figure 2). The number of ERC awards hosted by LSE tailed off from 2018, but three starting grants, two consolidator grants, two advanced grants, and one proof of concept grant were awarded in 2021 in the first round of Horizon Europe. This strong recovery was attributed to concerted efforts encouraging applications to EC and ERC programmes, albeit with the guarantee of UK government funding. The overall value of EU awards obtained in 2021/22 represented 30.8% of LSE total grant value, near to pre-referendum levels.

Figure 2: LSE sources of EU research funds 2015−2021

Source: LSE Grant applications and awards database. Converis. Note: UK−EC and UK−ERC represent Horizon Europe guarantee EC and ERC awards through UK funding bodies.

Social science and humanities researchers in the UK, especially those at LSE, had little hope of equalling their outstanding success in obtaining EU awards under Horizon 2020. They recognised that the rules of engagement outside the EU, even with associate status, meant they would no longer be entitled to draw more from the EU pot than they contributed. Despite its global reputation, LSE’s narrow disciplinary focus put it at a disadvantage in relation to much larger institutions where social sciences were already in close contact with the natural sciences. Supported by their science parks and close links with industry, these other universities did not need to rely so heavily on EU funding and networking.

The uncertainty created by the delay in signing the association agreement and the inconsistency of the guarantees offered by the UK government for UK-based researchers prompted LSE’s efforts to search for other ways of retaining staff and securing funding guarantees. However, none of the alternative schemes implemented by the UK government reassured the LSE research community that they would be adequately compensated for the loss of the funding and collaborative networks built up over almost four decades within the EU.

In recognition of the threats to its sustainability as ‘the leading social science institution with the greatest global impact’, in 2019 LSE’s Strategy for 2030 had set out plans to diversify its research income, stating that:

In the face of serious challenge to the research environment through our changing relationship with Europe and the uncertain future of national funding, we will work to secure sustainable funding for social sciences research by diversifying our income. We will do this through strengthening a culture of fundraising, enhancing support for external grant-raising, and growing our research commercialisation and consultancy activities.

While continuing to encourage their researchers to apply for Horizon Europe funding and contributing to visas and settlement costs for EU staff wanting to remain or come to the UK, LSE research managers turned their attention to strengthening pre-existing research collaborations with European colleagues and to developing their global reach in an ever-more competitive market for national and international research funds.

Note: The authors wish to acknowledge the contribution of colleagues at the London School of Economics for providing data on recent trends, in particular Crispin Williams for the LSE data analyses. This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Victoria Heath on Unsplash