In Confidence Culture, Shani Orgad and Rosalind Gill explore the demands that the cultural imperative of confidence particularly places on women. Enriched by abundant examples drawn from across popular culture to show how ‘confidence culture’ puts the onus on individuals to navigate and solve systemic problems, this book is necessary reading for scholars of gender, media studies and sociology, writes Ipsita Pradhan.

If you are interested in Confidence Culture, you can listen to a podcast and watch a video of the authors discussing the book at an LSE public event, recorded on 23 March 2022.

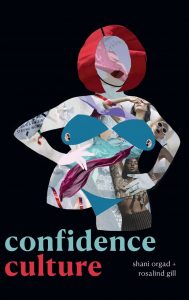

Confidence Culture. Shani Orgad and Rosalind Gill. Duke University Press. 2022.

Find this book (affiliate link):

Find this book (affiliate link):![]()

On most days there are WhatsApp updates from my phone contacts that have one variant of self-affirmation or another: ‘Today I will focus on what makes me feel good … I am capable of overcoming anything … I am deserving of what I desire and I will achieve it… I love myself’. What we see in these messages is today’s familiar terrain of ‘self-love’. While loving oneself can be an important reminder in contemporary times when one’s self-worth is often measured through one’s productivity, Shani Orgad and Rosalind Gill’s Confidence Culture assures us that these affirmations are not free from the disciplinarian gaze of the market and its neoliberal capitalist mechanisms.

Orgad and Gill waste no time in laying out the context and tackling the issue head on: the problem of confidence. How can confidence be a problem, one wonders? The authors point out that confidence has turned into a political project in branding, self-help guides, advertisements, motivational books and lectures as well as everything else that ‘popular feminism’ seems to foray into. Orgad and Gill interrogate this cultural imperative of confidence, which places the onus on the individual to navigate systemic problems: ‘as gender, racial and class inequalities deepen, women are called on to believe in themselves’ (1).

This exhortation to find an inward solution to an external obstacle is critiqued, taking examples from different spheres. They argue that the imperative to be ‘confident’ is essentially a gendered phenomenon as these exhortations are disproportionately focused on women. Theoretically, the authors draw from the Foucauldian notion of ‘technologies of the self’ to show how individuals engage with these wider, existing discourses in their lives. The constitution of this confident subject is seen through five domains of the everyday: the body; workplaces; relationships; motherhood; and in the sphere of international development at a macro level.

Image Credit: Photo by Prateek Katyal on Unsplash

The chapter on body confidence elucidates how confidence about one’s body has become a structuring idea under neoliberalism. Orgad and Gill critique the idea of confidence that emerges under ‘popular feminism’ as essentially problematic. Discussing different brands like Dove or L’Oréal, the diversity that different consumer products try to project falls flat because there is no radical divergence from the usually acceptable bodies of women, which still look glamorous, groomed and presentable. The authors therefore point out a pseudo-diversity in campaigns about loving one’s body. One interesting example they give is that of the Gillette campaign which emphasised women’s autonomy in the process of removing body hair without questioning the gendered act of body hair removal itself.

The following chapter takes on the issue of confidence at work and uses the examples of literature that talks about women in the professional space and what they can and must do to achieve success in largely male-dominated spheres. They agree that while the turn to this confidence narrative has brought issues like the gender pay gap to the fore, it still asks women to look inward to solve problems in their workplace to achieve personal growth and success. Women need to self-police to drive away negative feelings and keep motivating themselves to harness positive feelings. Thus, the norm of self-policing continues for women into another era. Being both vulnerable and confident in spite of these vulnerabilities that rest particularly on women is the new expectation.

The authors then take us into the domain of intimacies – confidence in relationships. Interestingly, this chapter looks at how intimate relationships, both with the self and others, are seen in neoliberal terms. They point out the use of phrases like ‘work at marriage’, ‘invest time’ and ‘upskill’ through new sexual techniques, which can be rationalised and quantified to show one’s productivity. They also identify the inherent assumption of heterosexuality in the discourse that proclaims that ‘confidence is the new sexy’. And of course, this confidence can be achieved through commodities: for example, buying sexy lingerie if you need confidence in the bedroom! Confidence shifts from a progressive political project to a compulsory one. Furthermore, confidence does not exclude the relationship with oneself. Thus, we see the emergence of a plethora of confidence apps that try to instil self-confidence through regular voice exhortations.

The sphere in which women were assumed to be innately capable was mothering, but now even that aspect has been placed in doubt. Parents, especially mothers, are under constant pressure to be confident and particularly to raise self-confident daughters so that they can ‘take on the world’. The number one priority is for mothers to maintain an upbeat mindset, so that self-worth becomes an ‘echo’ from mothers to daughters. This narrative of manufacturing confidence in oneself and in others (especially daughters) does not help women because it adds emotional, mental and physical work to women’s already long list of daily labour. Instead of improving women’s wellbeing, confidence creates another ‘to-do list’ in their already packed schedule.

The authors turn their gaze to the sphere of international development in the final chapter, critiquing the patronising development paradigm. The privatisation of the development process through philanthrocapitalist initiatives, commodity activism and the wholesale osmosis of confidence from the Global North to the Global South is problematised. Giving multiple examples, the authors show that the way international development is structured in neoliberal times reflects the idea that the Global North can ‘save’ poor women from the Global South. Thus, the development process continues to be afflicted with the saviour syndrome, only now gift-wrapped in discourses of entrepreneurialism and empowerment.

In their conclusion, Orgad and Gill show that the transition from confidence to expressing vulnerabilities through confidence seems to be the larger narrative through which women are expected to ‘be’. Accordingly, popular feminism comes to emphasise homogeneity and erases the differences in women’s lives and experiences.

Is it possible to escape confidence culture? Perhaps not. Nevertheless, the authors show us that it might be possible to subvert, in small ways, the overwhelming imperative of confidence, even though it might be difficult to completely overthrow it. Lizzo’s case, amongst others, is an interesting take. The authors show how Lizzo, a hugely popular African-American artist, exists within the spectacle of body positivity yet resists the capitalist blanket of confidence culture. Her ways of being – through clothing, the lyrics of her songs and her practices of self-love – overthrow received notions of the ideal confident body. Through asserting her racial identity and speaking out about racism, she has exposed the futility of ideas like post-racism and post-feminism. Her public declaration of loving her body beyond the ‘trend’ of body positivity is simultaneously an acknowledgement of the façade of such trends and a commitment to issues of feminism and inclusivity in a more meaningful sense.

Confidence Culture offers critical feminist insight into the conditions shaping our existence, experiences and our feelings. The abundance of materials from case studies, films, books, magazines and apps enrich the work. However, it would also be interesting to listen to the voices of women who are affected by the cult of confidence or its absence in different domains and the multiple meanings associated with this all-encompassing discourse. For instance, it would be a fruitful exercise to see how this work applies in different geographical contexts, such as South Asia or Africa. Confidence Culture is nonetheless an absolute necessity for scholars of gender, media studies, sociology and other interdisciplinary areas.

Note: This review first appeared at our sister site, LSE Review of Books. It gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Christine Ragudo from Pixabay