Most mainstream political parties in EU member states are supportive of European integration. Yet as Christian Freudlsperger and Martin Weinrich write, there is substantial variation in the kind of Europe they support. Drawing on a new study, they show how distinguishing between a ‘redistributive’ and a ‘regulatory’ polity can help explain the nature of this debate.

In the autumn of 2011, Angela Merkel’s ‘small’ coalition partner edged dangerously close to prematurely ending her chancellorship. At the height of the eurozone crisis, the liberal FDP, which is also part of Germany’s current ‘traffic light coalition’, asked its members for their stance on the European Stability Mechanism (ESM). A mere 54 percent endorsed the EU’s then novel 800-billion-euro bailout fund.

The result led to a collective sigh of relief in Berlin and Brussels, but the FDP has since remained anxious to avoid any semblance of European solidarity. During the eurozone crisis, many of its parliamentarians remained hostile to fiscal support for member states on the brink of bankruptcy; during the refugee crisis, its chairman argued against a permanent relocation mechanism; and during the Covid-19 pandemic, the party opposed the 750-billion-euro recovery fund.

To be clear, the FDP is not and never has been a Eurosceptic party. Scientific indicators such as the Chapel Hill Expert Survey have shown this time and again. The FDP simply has a distinct understanding of what the EU is and shall be. It considers national self-reliance and a ‘healthy’ competition among member states as core values of European integration. The role of EU institutions is to support this competition by means of regulatory interventions. In turn, the FDP sees European solidarity, whether by redistributing money or refugees, as an irresponsible invitation for ‘moral hazard’.

The case of the FDP demonstrates two things. First, while the scientific literature is certainly right in stressing that mainstream parties overwhelmingly favour European integration, it is largely agnostic to differences in the kind of Europe they support. The FDP, however, has a wholly different kind of Europe in mind than the social-democratic SPD or the Green party (which might explain the traffic light coalition’s oddly passive stance on Europe).

Second, the ‘polycrisis’ of the past fifteen years and the increasingly fervent politicisation of European affairs brought to the fore a dualism between proponents of European solidarity and national self-reliance. Different ideas about the finalité of European integration have always existed, but the polycrisis required domestic parliamentarians to take sides. As a consequence, even government MPs in countries like Germany began voicing open criticism of EU policies.

In a new study, we conceptualise this development as a competition between the idea of a ‘redistributive’ and a ‘regulatory’ polity. Proponents of the ‘redistributive polity’ support European solidarity with burden-sharing among member states. They regard the EU as a transnational political community that produces and provides scarce collective goods to states and citizens.

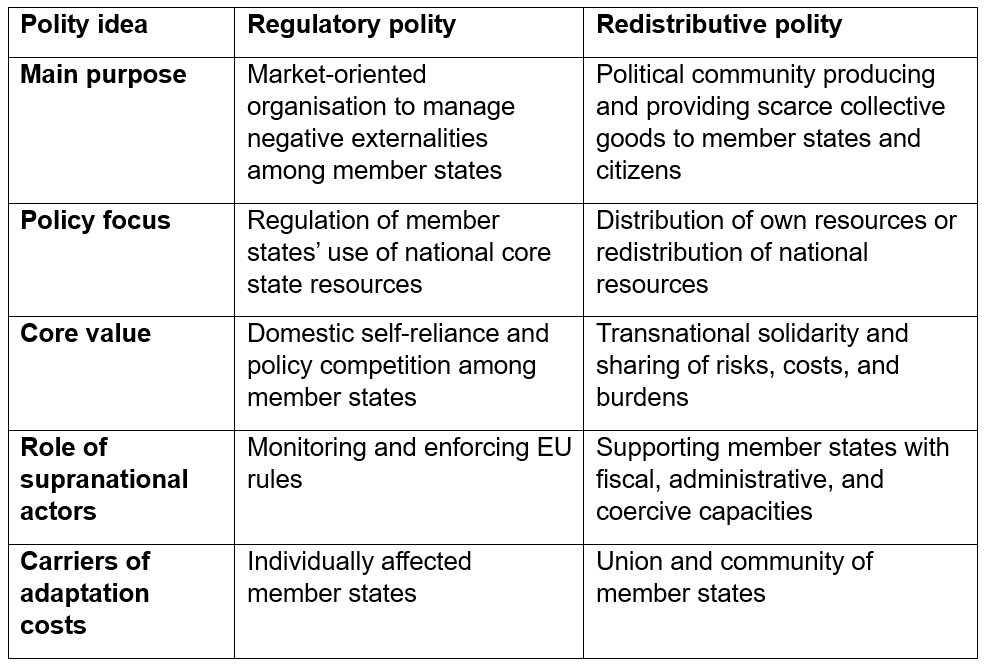

On the other hand, supporters of the classic notion of the ‘regulatory polity’ see the EU as a market-based organisation to manage externalities between states. EU institutions, in this view, are important to monitor and enforce EU rules, but the member states are solely responsible for adapting to common European standards and mobilising the resources to enhance the welfare of their citizens. Table 1 juxtaposes these two ideal-typical polity ideas.

Table 1: Features of a ‘regulatory’ and ‘redistributive’ polity

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper.

In our paper, we trace these two opposing ideas of Europe in parliamentary debates on core state powers in the German Bundestag between 2002 and 2019. For our analysis, we chose all 63 debates following a chancellor’s government declaration on a meeting of the European Council. Our dataset contains 811 speeches and 1,594 positional statements supporting either the regulatory or redistributive polity.

For our purposes, Germany is an interesting case for two reasons. First, it is a least likely case for an endorsement of transnational solidarity. As an affluent country with abundant state capacity, it has been a net payer into the EU budget and is more likely to exercise solidarity than profit from it. Second, Germany is a least likely case for party-based polarisation over Europe. Germany’s party landscape has long been traditionally characterised by a ‘pro-European consensus’ among mainstream parties with few threats from Eurosceptic challengers.

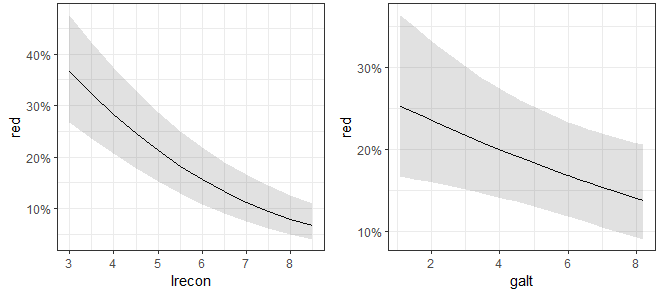

Figure 1: Results of the analysis

Note: The figure shows predicted probabilities of support for the redistributive polity (red) for parties’ socio-economic (lrecon; left) and socio-cultural (galt; right) position, full model.

Employing logistic regression, we show that German mainstream parties indeed differ quite drastically in their support for a regulatory or redistributive EU. They regard the EU through the prism of their ideology and, on this basis, lean more towards policies emphasising transnational solidarity or national self-reliance.

We find that socio-economically left-wing parties in Germany are more likely to support the redistributive polity than socio-economically right-wing parties (see Figure 1). Interestingly, we find a smaller and less significant relationship between parties’ socio-cultural positioning, which ranges from progressive to conservative (shown in Table 2 in our full paper). This finding qualifies a sizeable literature that has stressed the increasing importance of parties’ socio-cultural stance on their support for European integration, and demonstrates the continued relevance of the socio-economic left-right dimension for the party politics of European integration.

Our findings have two broader implications for the course of European integration. First, a solidifying rift between solidarity and self-reliance could provide mainstream party voters with a meaningful choice between different normative conceptions of the EU. This could nag at Eurosceptic parties’ electoral appeal.

Second, while the generalisability of our findings beyond Germany is a matter for further research, centre-left parties in net-contributing member states that are to exercise solidarity, particularly in the North, are in a potentially pivotal position. In countries that profit from transnational solidarity, especially in the South, we can assume broad support for redistribution across mainstream parties. In countries likely to exercise solidarity, we observe the fiercest resistance to redistributive ideas.

Were northern centre-left parties to advocate solidarity as well, they could tip the power balance inside European institutions. If the regulatory integration of core state powers is indeed a main cause of the EU’s current malaise, this change could open a path out of the seemingly never-ending succession of EU crises. The FDP, however, would most certainly disagree.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the Journal of European Public Policy

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Union