Robert Fico’s Smer won the most seats in Slovakia’s parliamentary election on 30 September. Tim Haughton, Darina Malova and Kevin Deegan-Krause highlight four key factors that shaped the result.

Politics may not always be local, but it is invariably domestic. Judging from most international media coverage of last weekend’s elections in Slovakia, readers might assume the strong performance of Robert Fico’s Smer (“Direction”) was driven by his criticisms of the West’s support for the war in Ukraine. But voters made their choices largely based on domestic factors.

The election indicated a country that had lost faith in a chaotic government, but without losing faith in democracy overall. Moreover, it highlighted an electorate searching for competent leadership or clean governance, or for a sizeable slice of voters, both. Four factors, in particular, shaped the outcome.

Voting for and voting against

An old adage in politics is that oppositions don’t win elections, governments lose them. Although complicated by the fact Slovakia has been governed by a caretaker administration for several months, the election was partly a verdict on the parties that formed the government after the 2020 election. After winning enough votes to create a constitutional majority in parliament in 2020, support for those parties that had promised a combination of clean governance and leadership slumped to a combined total of just 17%.

The challenges of dealing with a global pandemic and the economic consequences of the Ukraine war were tough asks for many governments across Europe, but the drop in support for the government initially led by Igor Matovic, and subsequently by Eduard Heger, owed much to the style of governance.

Whilst ordinary Slovaks worried about the impact of COVID-19, the state of the health system and pressures on their finances, politicians in the governing coalition bickered. Thanks to policy differences and personality clashes, the coalition disintegrated, leading to the creation of a caretaker government, and eventually early elections.

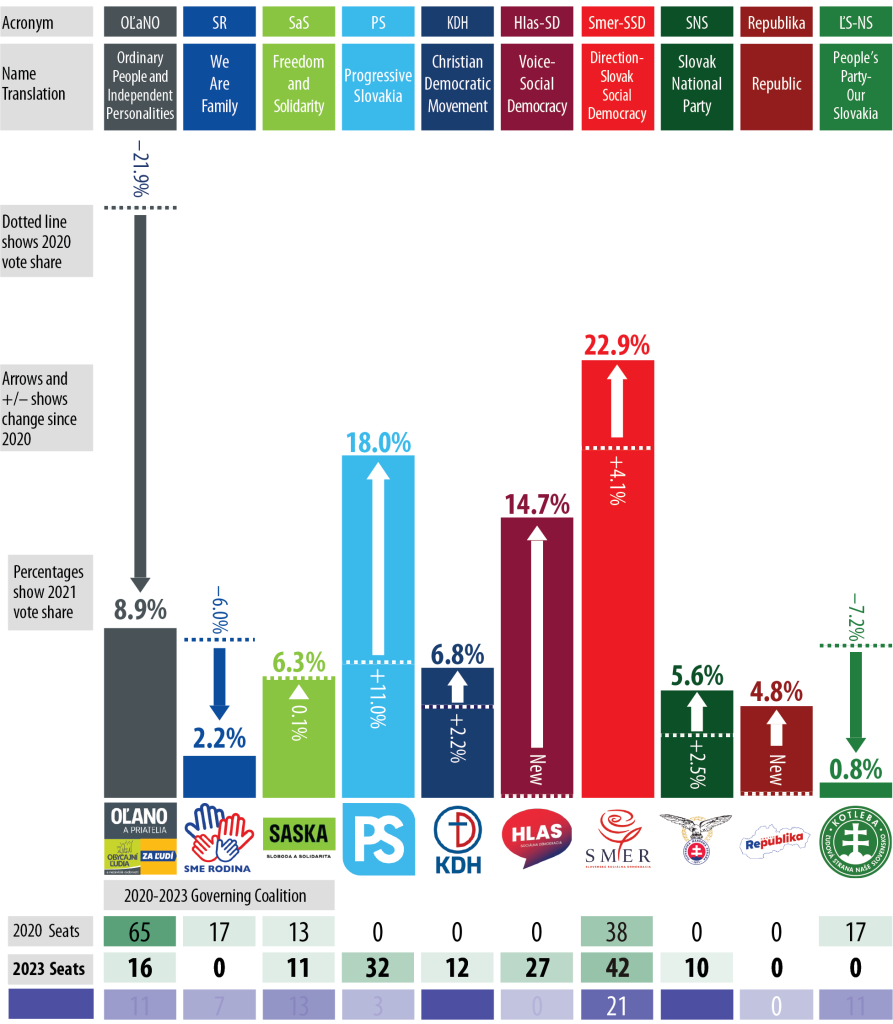

Figure 1: Slovakia’s 2023 election at a glance

Source: Statistical Office of the Slovak Republic and authors’ data. For details, contact Kevin Deegan-Krause.

The chaotic nature of politics played into the hands of Robert Fico. In spring 2020 it looked like the time to write his political obituary. His Smer party had lost the 2020 election and several of his former lieutenants had broken away to form a new party, Hlas (“Voice”).

But Smer bounced back. Central to Fico’s success was his promise to provide stability, “poriadok” (order) and effective leadership. The three-time prime minister could point to his previous stints in government that had delivered economic growth and social welfare measures. Using a line he had deployed to great effect in previous elections, he depicted the choice facing Slovaks as a government led by Smer or a chaotic “zlepenec” (“a glued together hack job”) that would come unstuck.

Smer’s stints in government were marked by scandals and murky links between politicians, businessmen and organs of the state. The prospect of Fico returning to power provided a key frame for the socially-liberal and economically reformist Progressive Slovakia (PS). Although PS’s leader, Michal Simecka, was keen to burnish the party’s expertise and offer an extensive programme of policy solutions in its “plan for the future”, the key mobilising message for Simecka was to stop Fico’s return to power.

Campaigning matters

Effective campaigning around corruption was also central to one of the surprises of election night. Igor Matovic’s Ordinary People (OLaNO) had hoovered up a quarter of the vote in 2020 on a strong anti-corruption message. But the party had fractured and seen its vote drop thanks in no small part to Matovic’s chaotic governing style as prime minister and subsequently as finance minister. He had become one of the most distrusted politicians in the country. Yet, OLaNO won just shy of 9% of the vote.

Some politicians, like Matovic, are better suited for campaigning than executive office. Matovic’s aggressive style and crude rhetoric was well illustrated by his violent altercation with leading figures in Smer when he gatecrashed a Smer campaign press conference, labelling Fico’s party “a bunch of mafioso”. The kicking and the punches thrown may have generated negative international coverage, but they helped mobilise core OLaNO voters around the message that Matovic is the man to fight corruption.

Campaigning messaging also holds the key to one of the other surprises of the election. Opinion polls had consistently suggested the neo fascist Republika party would cross the 5% threshold. But mixed into his appeals stressing leadership and left-leaning solutions, Fico added a strong message on migration and defending national interests, seducing some Republika voters into supporting Smer.

Electoral system effects

The 2023 election also marked the political comeback of two of Slovakia’s oldest parties: The Slovak National Party (SNS) and the Christian Democratic Movement (KDH). The return of SNS to parliament owed much to the workings of list-based voting in Slovakia’s proportional representation system.

Lists are open, allowing voters to express up to four preferences for particular candidates. Party leaders keen to boost the overall support for their parties offer places on the lists to individuals and organisations. But that element of the electoral system can yield unexpected outcomes. In the case of SNS, the only party member elected amongst its ten strong contingent in parliament is the leader Andrej Danko, which poses serious questions about the cohesion of SNS (itself a mini “zlepenec”) in parliament and in any government.

Ideological choices and party structures

The return of KDH to parliament after a seven-year absence lies in a combination of extensive party structures and its leader Milan Majersky’s record in subnational politics in eastern Slovakia, but also KDH’s conservative catholic values. The ability of Freedom and Solidarity (SaS) to retain its parliamentary representation, despite its role in the spats and chaos of the OLaNO governments, owes much to the appeal of its liberal, pro-market ideological stance to its core voters.

Slovakia’s new parliament represents a range of ideological views reflecting the diversity of opinion across the country on social and economic issues. However, whether some of the ideological views expressed in the campaign were genuine rather than just window dressing for the campaign remains to be seen.

In particular, there are clear question marks over the motivation of Hlas and its leader Peter Pellegrini. A breakaway from Smer, Hlas has sought to project itself as a modern European social democratic party. During the last week of the campaign, Pellegrini sent out mixed signals: on the one hand ramping up anti-migration rhetoric, but on the other stressing that the overall election campaign was too much about who or what someone is against rather than focusing on the issues that matter to ordinary Slovak citizens.

All potential majority coalitions involve Hlas. Negotiations over the coming days will indicate the depth and strength of Pellegrini and his party’s commitment to social democratic values. The most likely coalition involves Hlas joining forcing with Smer and SNS, but a four-party coalition led by PS remains a distinct possibility. Hlas’s voice will be decisive in determining the direction of Slovak politics.

But whatever decision Pellegrini makes, the “stable instability” of Slovak party politics, fuelled by the search for clean governance and effective leadership, looks set to continue.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Union