Among European countries, the UK stands out as one of the first to transform into a free market for labour. Yet, as Gwyn Bevan argues, the financialisation of its housing market, the need for an elite education to secure a “glossy job” and the economic hegemony of London have made inequality in the UK entrenched to a degree unparalleled in Europe or the United States.

In August of this year, in the Financial Times, John Burn-Murdoch estimated the marginal impacts of removing one city on a country’s GDP per capita. The effect of removing Amsterdam from the Netherlands would be five per cent, the San Francisco Bay Area from the United States would be four per cent, and Munich from Germany would be one per cent. But, for Britain, removing London reduced GDP per capita for the rest of the UK by 14 per cent, making it poorer than Mississippi.

Europe’s geographic fault lines

Fault lines of inequalities across Europe developed after waves of the Black Death in the 14th century. That remains the deadliest global pandemic in human history: in 1348-49, the first of four waves reduced England’s population by over 30%, in comparison, the death rate from COVID-19 in the UK has been about 0.3%. As John Hicks has argued, the shortage of labour from the Black Death resulted in the ending of feudalism in much of western Europe (in the UK there was the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381), but not in Russia; nor in southern Italy as argued in the classic study by Robert Putnam et al.

The consequence for Italy, is its North/South fault line. Social capital developed over centuries in northern Italy, but its absence in southern Italy enabled the development of its varieties of organised crime, in Sicily (Mafia), Campania (Camorra), and Calabria (‘Ndrangheta). In Russia, the success of landlords in imposing a second serfdom meant that feudalism continued until the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, which meant that the Soviet variety of communism developed without social capital.

The extension of Soviet communism after the end of the Second World War created new fault lines in Europe. In 1991, Angus Maddison estimated the GDP per capita of East Germany was 28 per cent of that for West Germany. So how does regional inequality in the UK now compare with that of Germany (after over forty years of communism in the East) and Italy (with its varieties of organised crime in the South)?

The UK as an outlier in Europe

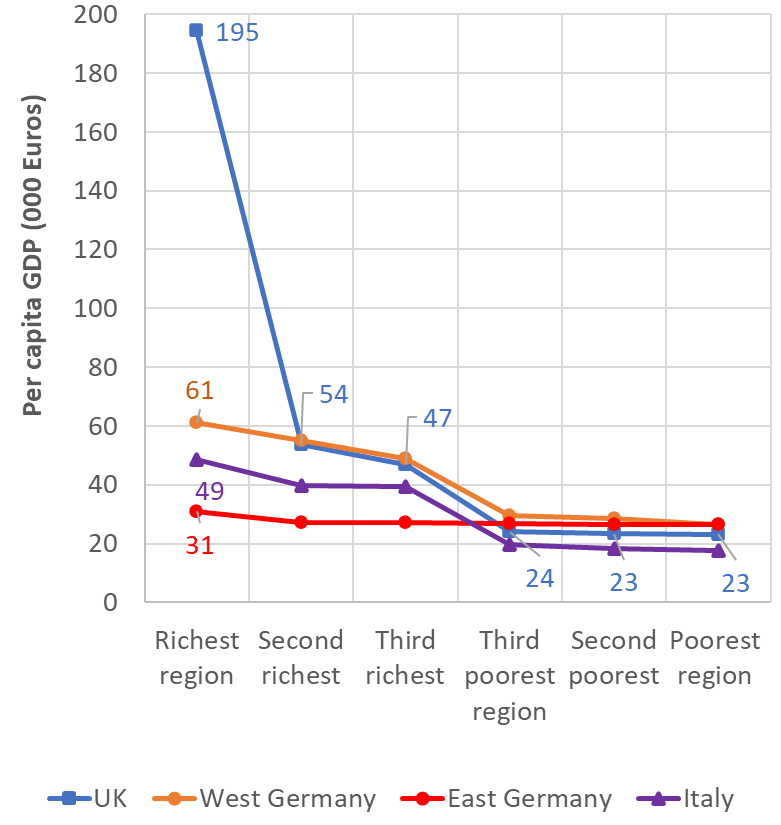

Figure 1 gives estimates of GDP per capita for 2019 for the three richest and poorest regions in the UK, Italy and West and East Germany (in euros from Eurostat and the ONS). This shows that the regions of East Germany were richer than the three poorest regions in Britain; and Italy’s three poorest regions were Campania, Sicily and Calabria.

The richest and poorest regions in the UK were Inner London – West (£188,000) and Tees Valley and Durham (£22,400). In Italy, the respective regions were Bolzano (£46,900) and Calabria (£17,000), while in Germany, they were Hamburg (£58,800) and Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (£25,600).

Figure 1: GDP per capita in 2019 in euros for the richest and poorest regions in East Germany, Italy, the UK and West Germany

Source: Eurostat and the ONS

The GDP per capita of the richest region was eight times that of its poorest in the UK, but only three times in Italy and (united) Germany. The UK is an outlier and not because Inner London – West has a small population: its 1.2 million is comparable with Hamburg (1.9 million) and more than twice that of Bolzano (0.5 million).

Indeed, the two richest two subregions within Inner London – West (Camden and City of London, and Westminster) have a combined population similar to Bolzano and an estimated average GDP per capita of £360,000. So how have Britain’s systems of governance created such extreme regional inequalities with neither the handicaps of decades of communism nor organised crime?

Income and place

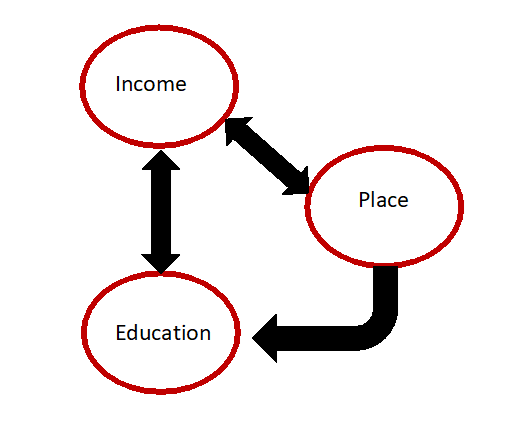

Figure 2 indicates the nature of Britain’s systemic feedback between place, education, and income. Tom Archer and Ian Cole have estimated that the financialisation of housing production has increased the average profit by private builders on each completed house from £6,000 in 2009 to over £60,000 in 2017. Wendy Wilson and Cassie Barton explain that the prices of “affordable” housing are defined with reference not to earnings, but to prevailing market rates.

Figure 2: Systemic feedback between place, income and education

Note: Created by the author

They estimated that in 2021, median house prices in England were over nine times median full-time earnings, and 28 times earnings in the least affordable area (Kensington, where Grenfell Tower is located). Anne Minton explains how London’s housing market is perfectly designed for the “champagne tower effect” in which billionaires displace multi-millionaires from the top addresses, so they in turn displace millionaires. Equity migrates to the more peripheral areas of the capital and, eventually, out of the capital to the rest of the UK.

Education

Although, in principle, parents can choose schools in England, Simon Burgess et al have found that geographic proximity continues largely to determine access to high-performing schools that are oversubscribed. Hence the educational values of a good school are capitalised in the housing market.

These values can only have been inflated by the shift in Oxbridge admissions away from England’s private schools. In the Financial Times, In 2021, Brooke Masters reported how one parent who wondered in 2021 about the value of paying “the thick end of half a million quid (aged 4-18) per child pre-tax to send them to private school”; and, in 2023, Alexandra Goss, using data from estate agents, indicated that £500,000 is the premium that parents can expect to pay, to buy a house in a good school, in the desirable areas of London, Birmingham, Manchester and Liverpool.

A good degree from one of Britain’s elite universities helps in the struggle for what Harvey Markovits describes as “glossy” jobs. These are concentrated in Britain’s “golden triangle” (London, Oxford and Cambridge), where housing is unaffordable without a loan from the bank of mum and dad.

The financialisation of the housing market is why Britain’s geography is “becoming destiny” for so many people, with where you are born determining your life chances. That market is designed to offer opportunities for conspicuous consumption by the super-rich, a safe haven for the capital of foreign investors and generous profits for those engaged in the building and selling of houses and flats – while making houses unaffordable for most households seeking good schools and “glossy” jobs.

Gwyn Bevan’s new book, How Did Britain Come To This? A century of systemic failures of governance, is available from LSE Press as a free download

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: andersphoto/Shutterstock.com