The political beliefs of parents have an important impact on their children. But how do these dynamics play out in countries with multiparty systems, where there is greater potential for mixed signals? Drawing on new evidence from the Netherlands, Linet R. Durmuşoğlu illustrates how parents shape their children’s engagement with politics.

Parents serve as a crucial source of political information for adolescents navigating the complex world of politics. Although extensive research exists on how the intergenerational transmission of political preferences takes place in two-party systems, such as the United States, little is known about how this works in multiparty systems. However, in recent years, a growing body of research explores how young individuals in multiparty contexts, especially in western Europe, form their political orientations.

The most important differences to consider when comparing political socialisation in two-party to multiparty systems are increased volatility and fragmentation in multiparty systems, as well as lower levels of party identification. These differences present youngsters learning about politics in multiparty systems with distinct challenges.

Firstly, they must acquaint themselves with numerous and sometimes rapidly changing political parties and form opinions about them. Secondly, when it comes to learning about politics from their parents, these adolescents are more likely to encounter mixed signals, given their parents often lack strong affiliations with a single party and frequently change their voting preferences.

This makes it likely that ideological orientations play an important role in the political development of these adolescents because they are more stable over time, often staying relevant throughout an entire lifetime, and therefore have higher heuristic value. Given that left-right orientations emerge as the most important predictors of party preferences in many western European countries, they are likely to play an important role in parental political socialisation in multiparty contexts.

Evidence from the Netherlands

Together with Wouter van der Brug, Theresa Kuhn and Sarah de Lange, I have conducted two studies examining how adolescents in multiparty systems acquire political preferences, more specifically party preferences, left-right orientations and issue attitudes, from their parents.

For these studies, we have collected survey data from Dutch adolescents and their parents over the span of three years. The questions we asked ranged across various topics, such as their political preferences, but also their political behaviour and knowledge, media usage and interactions with socialisation agents like their families, school and peers.

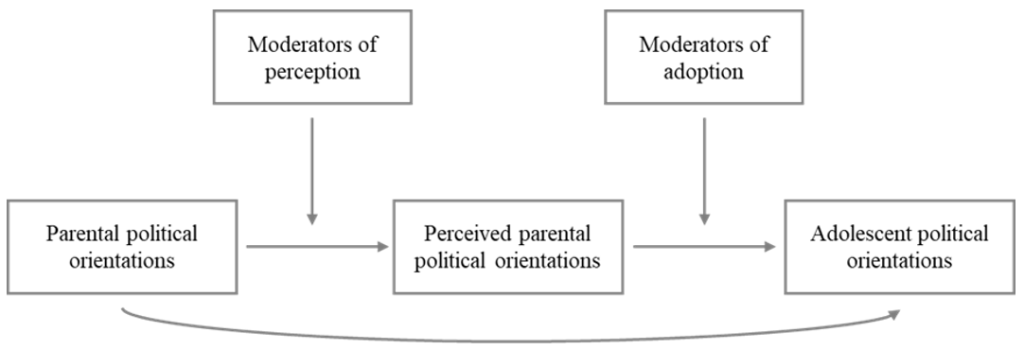

In the first study using this original data, we investigate which role left-right and issue orientations play in the parental socialisation of party preferences and examine the following model of intergenerational transmission (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Model of intergenerational transmission of party preferences

Note: Compiled by the author.

Our results show that Dutch parents’ party preferences and left-right and issue positions have a strong direct effect on those of their children. Most importantly, we demonstrate that parents also affect their children’s party preferences indirectly by transmitting their left-right and issue positions to them. These findings underscore the importance of considering more stable political orientations when examining the development of party preferences in multiparty contexts.

At the same time, our findings show bidirectional transmission effects, meaning that the left-right and issue positions of adolescents also influence the party preferences of their parents. This finding points towards the agency that children have in intergenerational transmission processes, a topic that has gathered increasing interest during recent years.

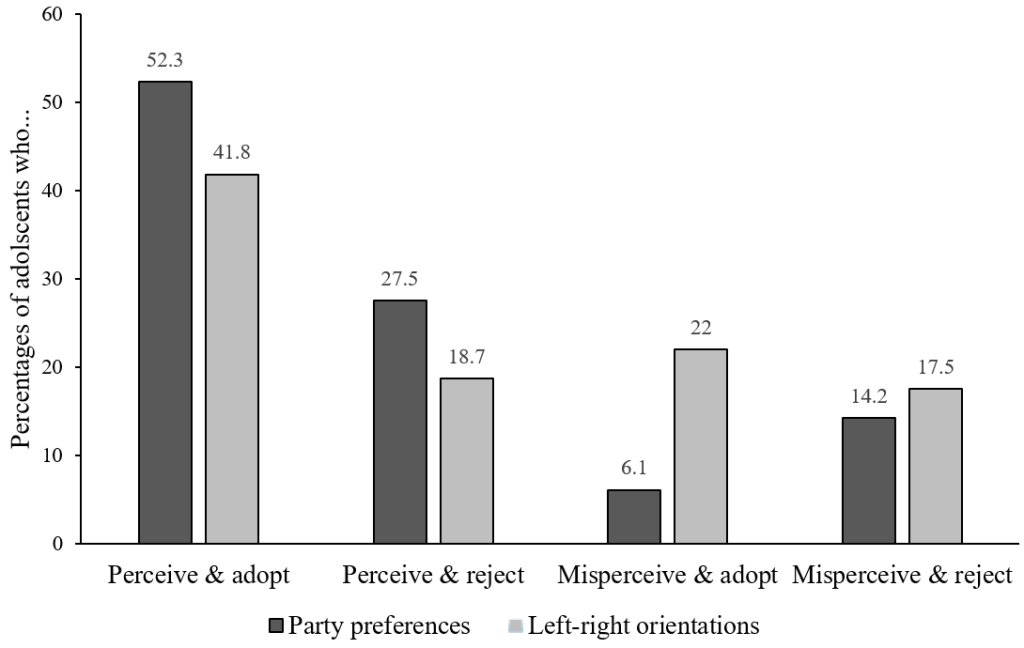

In a second study, I examine the applicability of a new approach to parental socialisation developed by Peter Hatemi and Christopher Ojeda to multiparty contexts. This approach assumes that children’s perceptions of their parents’ political preferences are crucial in the transmission process. Building on the findings of our first study, I not only examine the intergenerational transmission of party preferences but also the transmission of left-right orientations.

Figure 2: The perception-adoption approach to parental socialisation

Note: Compiled by the author.

As illustrated in Figure 2, the perception-adoption approach assumes that children first perceive the political orientations of their parents (correctly or incorrectly) before deciding whether to adopt those perceived orientations. This leads to four possible outcomes of intergenerational transmission processes: correct perception and adoption, correct perception and rejection, misperception and adoption, and misperception and rejection. The data from the Netherlands shows that adolescents find it more difficult to correctly perceive the left-right orientations of their parents than their party preferences, but that both perceived parental party preferences and left-right orientations are adopted at similar rates.

Figure 3: Adolescents’ perceptions and adoption of their parents’ party preferences and left-right orientations

Note: Compiled by the author.

In both these studies, several characteristics of the adolescents, their parents and the household dynamics were examined to disentangle their possible impact on the transmission process. Both studies highlight the importance of discussions in the family about politics as a moderator of intergenerational transmission. Frequent discussions about politics between adolescents and children leads to stronger transmissions generally and more specifically to a higher likelihood of adolescents correctly perceiving the political orientations of their parents.

At the same time, those adolescents that do not often talk about politics with their parents and are not politically knowledgeable and engaged run a high risk of not being politically socialised by their parents. Besides the transmission effects from parents to children being weaker in these groups, we also see that these adolescents struggle to correctly perceive their parents’ political preferences, especially their left-right orientations. As these less politically sophisticated adolescents are also precisely the ones that would benefit the most from the heuristic value of left-right orientations in guiding them in their political decision making, this is worrying from a democratic point of view.

Implications for parents and practitioners

These findings have implications for parents that seek to socialise their children politically, but also for practitioners in the field of civic education. The most obvious implication is that parents should not underestimate the impact they have on their children and should actively engage their children in discussions about socio-political topics.

While engaging adolescents in these discussions, and while actively teaching them about politics, both parents, teachers and others involved in civic education should be aware of the importance of stable ideological orientations that help adolescents understand the structure of the party landscape and match their own attitudes and values to the right party.

In follow up research, we are now taking a closer look at the influence that children have on their parents. Finding a path of transmission from children to their parents would open up an avenue to influence the political knowledge and engagement of families through civic education in schools, which would be good news for households that are not politicised and consequently for the functioning of representative democracy.

This might mean that parents that have missed important steps in their political development, either because they came from disadvantaged households or, in the case of migrants, were socialised in completely different environments, could learn about politics from their children.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying papers in Political Psychology and Electoral Studies

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: iVazoUSky/Shutterstock.com