It is common to refer to party families such as “social democrats” and the “radical right” when discussing European politics. Drawing on a new book, Peter Egge Langsæther writes that while these definitions are important, categorisations should be treated carefully as they can have a major impact on research conclusions.

Party families have long been regarded as a valuable research tool in political science, going back to the influential studies of Klaus von Beyme and Daniel-Louis Seiler in the 1980s. Party families serve to categorise parties in the examination of electoral behaviour, party politics, legislative behaviour and public policy, among other areas of study. As an example, many have analysed the decline of social democratic parties, assuming that parties labelled “social democratic” share common characteristics resulting in their decline across different countries.

However, the shared traits among parties from various party families are far from clear. In fact, the definition of a party family and the rationale behind grouping parties in a particular manner, as well as their supposed similarities, remain ambiguous. Many applications of this concept either group parties together in a somewhat arbitrary fashion, refer to previous classifications that have done the same, or employ proxy criteria such as international affiliations or historical origins to establish classifications.

In a new book, I aim to address these limitations in three ways. First, by providing a clearer conceptual understanding of what constitutes a party family. Second, by offering updated categorisations. And finally, by providing contemporary descriptions of the party families and their supporters.

Conceptual understanding

In terms of conceptual understanding, there are essentially three main perspectives. The first – the genetic approach – focuses on parties’ origins. While this approach is firmly rooted in cleavage theory, a challenge arises as such origins may become less relevant in explaining parties’ behaviour over time.

For instance, parties belonging to the radical right cannot be solely differentiated based on their shared origins as many initially formed as anti-tax protest parties. Nevertheless, the radical right remains an important and extensively studied party family. Therefore, relying solely on historical origins to classify parties raises uncertainty regarding the commonalities they possess today.

Self-identification, especially through international affiliation such as in European Parliament groups, is another widely used criterion. This approach is easy to implement and has a high level of validity as parties are well-positioned to judge who share their characteristics. However, this approach is also fraught with issues.

One significant challenge is that it remains unclear what parties in a European Parliament group have in common. Some may join a group because they share a political vision, while others may do so based on strategic domestic considerations. For example, until recently, radical right parties refused to cooperate with each other at an international level to avoid being associated with other parties considered extreme.

An amusing instance is that of the two major Irish parties, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil. Fine Gael joined the European People’s Party before accession, so Fianna Fáil had no option but to join another group. This was not attributable to ideological reasons but rather to maintaining the appearance of political differentiation for domestic reasons. Lastly, several eastern European countries joined European Parliament groups and adopted particular labels for strategic rather than ideological motives.

Therefore, I argue that we must consider party families as groups of parties that share a set of core ideological features, which can and should be measured. This approach leads us to be explicit about how we believe parties in a family are similar and based on what empirical evidence we conclude this.

I delineate core ideological characteristics for each party family and gauge their presence through expert surveys. For instance, I build upon Cas Mudde’s work to argue that nativism and authoritarianism are essential ideological features of the radical right. I suggest such ideologies should be reflected in policy positions (such as anti-immigration and law-and-order policies) and salience (high salience of the immigration issue) and I test whether this holds true for parties usually considered to belong to the family.

However, I welcome and acknowledge that others may hold different opinions regarding the ideological features or their measurements. For instance, one could potentially use the Manifesto Project or employ qualitative, in-depth analyses of each party. The key point is that we need to be explicit about how we define a party family and determine whether a party fits within this family empirically.

Updated categorisations

My second contribution is an updated classification. Drawing upon Luke March’s research, I define the radical left as parties positioned to the left of social democracy that reject certain crucial components of contemporary capitalism and advocate for substantial resource redistribution. I argue that this stance should be reflected in a far-left position.

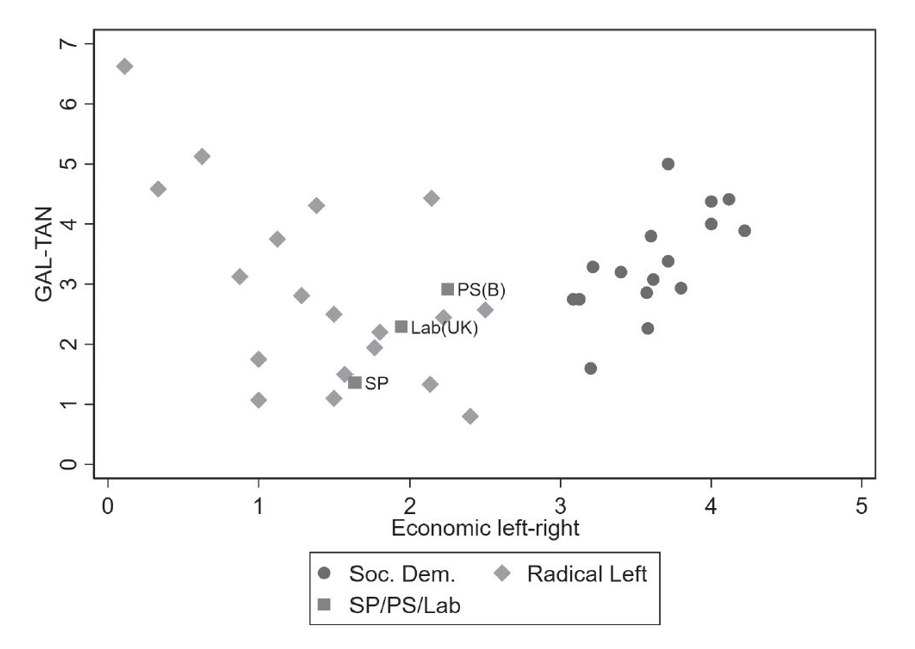

Figure 1: A reclassification of social democratic parties

Note: For more information on this chart, see page 93 of the author’s accompanying book.

Figure 1 depicts the positions of parties typically considered social democratic and those typically seen as radical left on the economic left-right ideological spectrum (ranging from 0 to 10, constrained to 0-5 in this case). Three parties stand out by being situated to the left of other parties generally perceived as social democratic.

One of these is the UK Labour Party. However, this position was short-lived during Jeremy Corbyn’s leadership, so I refrain from reclassifying this party. On the other hand, experts deem the Belgian Parti Socialiste and the Swiss Social Democrats to be extremely left-wing in absolute terms (hovering around 2 on the 0-10 scale). These parties are located multiple standard deviations to the left of other social democratic parties and even to the left of radical left parties such as Syriza or Podemos. Consequently, I reclassify these parties.

Party families

Finally, I focus on the party families themselves. I document the electoral performance of party families over time, highlighting cross-country trends and deviations from these trends. I also examine government participation patterns and party supporters, evaluating both their social background and political values.

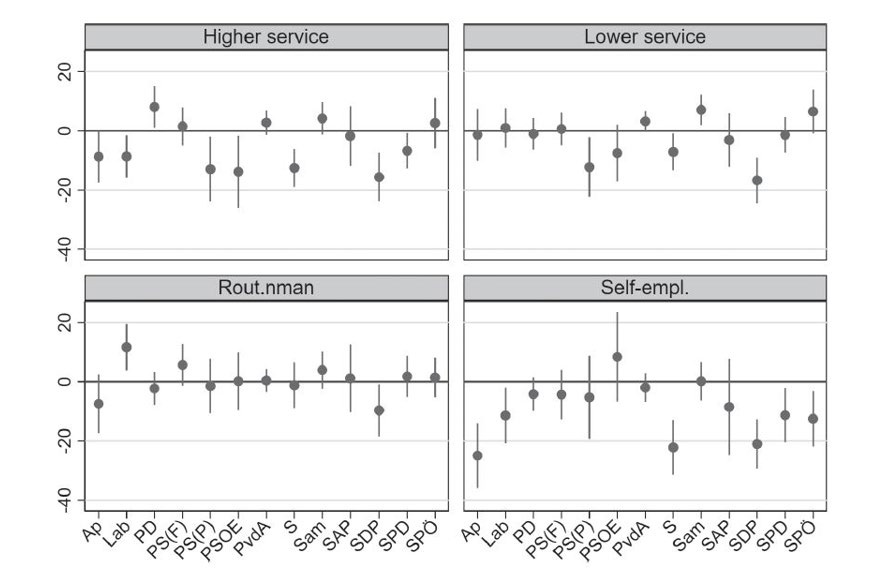

For example, Figure 2 depicts the class basis of social democratic parties. In contrast to the widely held notion popularised by notable social scientists such as Thomas Piketty, I observe that these parties have not transformed into middle-class parties. Rather, their support base presently reflects a coalition incorporating the working class and select portions of the middle class.

Figure 2: The class basis of social democratic support

Note: The horizontal line represents the level of support among the working class for each party, the dots indicate the difference between the workers and the relevant class in the panel, and the lines indicate 95% confidence intervals. For instance, the higher service class is approximately 10 percentage points less likely to support Labour than the workers (see upper-left panel). For more information on this chart, see page 105 of the author’s accompanying book.

This partly accounts for the social democratic challenge today as groups within the middle class, who are more prone to agreeing with workers concerning left-wing economic issues, often disagree with them on matters such as immigration. As such, with the increasing weight accorded to these issues in European politics, social democrats are grappling with a new and harder type of dilemma than that portrayed by Przeworski and Sprague in the 1980s.

While scholars may have different views about defining criteria or how to analyse ideological similarity, I hope my research can contribute to these being made more explicit from now on. Party families are important research tools in political science that allow for generalised discussions about important political developments, but the choices we make when categorising parties may impact our conclusions when we study electoral behaviour or public policy making. Party families thus deserve to be treated more carefully and we should be mindful of the limitations of using ad hoc categorisations and implicit definitions.

For more information, see the author’s new book, Party Families in Western Europe (Routledge, 2023). R and Stata codes to recreate the party family schema for the European Social Survey, the European Values Study, the Chapel Hill Expert Survey and the Comparative Manifesto Project are available here.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: CC-BY-4.0: © European Union 2023– Source: EP