In December, EU leaders agreed to open membership talks with Moldova and Ukraine and to grant candidate status to Georgia. Visnja Vukov writes the EU must learn from previous EU enlargements by managing the developmental consequences of integration in each of the three states.

It is well established that integration among countries at different levels of development can create disadvantages for less developed countries. These include premature deindustrialisation, rising inequality and unemployment or fiscal losses.

This has been a long-standing challenge for the EU, which contains countries with vastly different levels of income. Many EU policies have been designed to address this challenge, including cohesion policies, rules concerning state aid and the distribution of European Investment Bank loans.

As the EU moves towards a further round of enlargement for Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, developmental disparities are likely to dramatically increase. The GDP per capita of these countries is only between 12% and 14% of that in the EU and the complexity and technological sophistication of their economies is far below those of EU member states in eastern Europe, let alone countries like Germany and Finland.

In addressing these challenges, lessons can be drawn from previous EU enlargements that included less developed economies. In the 1980s, the EU’s “southern enlargement” saw Greece, Portugal and Spain become members. More recently, in 2004 and 2007, the EU’s “eastern enlargement” resulted in 12 new member states joining, mostly from Central and Eastern Europe.

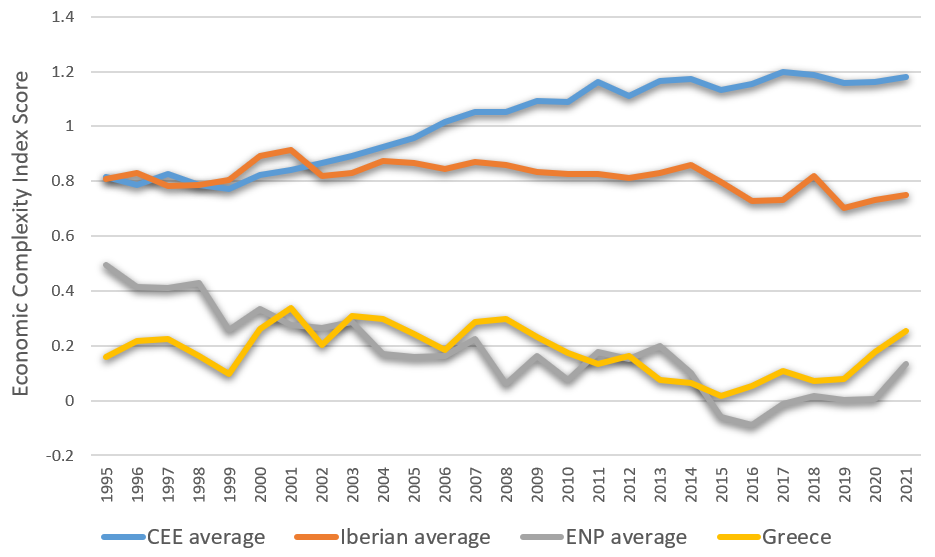

The two enlargements were managed by the EU in a dramatically different way and have given rise to very different developmental pathways and economic growth models. The diversity of developmental outcomes can be illustrated using an Economic Complexity Index produced at the Growth Lab of Harvard University. This captures the diversity, complexity and sophistication of a country’s exports.

Figure 1 shows changes in economic complexity in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE); in Portugal and Spain (Iberia); in Greece; and in Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine (referred to in the figure as “ENP” as these states participate in the European Neighbourhood Policy).

Figure 1: Changes in economic complexity (1995-2021)

Note: The figure is based on the author’s calculations using data from the Harvard Atlas of Economic Complexity. A higher Economic Complexity Index “score” indicates the country has increased its economic complexity. The CEE average includes Bulgaria, the Czech Republic, Hungary, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia. The Iberian average includes Spain and Portugal. The ENP average includes Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine.

The figure shows that countries in Central and Eastern Europe have not only seen economic growth but have also increased their economic complexity during their integration into the EU. In contrast, the countries in southern Europe experienced developmental stagnation from the mid-1990s, while Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, which have so far only had limited integration with the EU, experienced developmental decline during the same period.

The importance of state capacity

Market integration, which is intended to create positive economic effects, has indeed been associated with improvements in Central and Eastern Europe. However, it appears to have simply preserved the status quo in other cases or even had a negative impact. Why is this the case?

EU policies have likely played a crucial role in producing these outcomes. Previous research suggests differences in state capacity are important for development, such as the bureaucratic capacity of states, their relative autonomy and their ability to implement a coherent development plan. While these might be viewed as domestic preconditions, the EU’s approach to the eastern enlargement actively strengthened the state capacities of countries in Central and Eastern Europe, including those that initially had weak states.

The EU’s accession criteria for the eastern enlargement required states to have functioning market economies capable of withstanding competitive pressures in the common market. Coupled with pre-accession financial assistance, this helped increase state independence from the influence of domestic interests that might seek to preserve the status quo and thereby damage competitiveness.

The EU also demanded institutional changes that helped strengthen state institutions such as the judiciary and bureaucracy. In contrast with other international organisations, the EU went beyond simply demanding market liberalisation. Instead, it encouraged states in Central and Eastern Europe to create institutions that could implement market friendly industrial policies. This approach helped create “pockets of excellence” in the bureaucracies of Central and Eastern Europe, strengthening the ability of these states to improve their development.

This is evident in the different experiences of Romania and Ukraine. In Romania, market integration coupled with institution building allowed the country to strengthen its initially weak state capacity and reap the economic benefits of integration. Ukraine, in contrast, received trade liberalisation from the EU but without any requirements to improve state capacity. This prevented the country from making any developmental gains.

None of the demands placed on the eastern enlargement countries were applied to the southern enlargement countries when they joined in the 1980s. Rather than help these states manage developmental challenges associated with integration, the EU simply provided financial resources with few strings attached. More often than not, this funding simply enabled the southern enlargement states to strengthen their pre-existing growth strategies focused on infrastructure, construction and real estate.

These states did have to comply with some conditions before they could join the euro, but these conditions were not linked to development or to the ability to withstand competitive pressures in the common market. Consequently, while integration initially generated economic growth in the southern enlargement states, there was little effect on the complexity or technological sophistication of their economies. The apparent gains made after accession were quickly erased after the eurozone crisis.

Lessons for future enlargement

What lessons should the EU draw for its future enlargement? First, given their low levels of income and economic complexity, developmental challenges in the integration of Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine are likely to be even larger than for previous enlargement countries. Managing the developmental consequences of integration should therefore be a key priority for the EU.

Second, the EU should not trust that market integration on its own will lead to sustainable growth and economic improvements. Upgrading state institutions should be viewed as a key component of development. This includes the judiciary and bureaucracy, as well as institutions dealing with technological change and industrial policy.

Third, while financial assistance can help reduce disparities in a common market, the EU should explicitly include development goals in its integration agenda. It should also link assistance with efforts to increase economic complexity and diversify and upgrade a state’s participation in global value chains.

Finally, the experience of countries in Central and Eastern Europe shows that the success of integration also depends on how economic gains are distributed across different social groups. Discontent with the way these benefits are distributed can provide fertile ground for nationalism and illiberalism. It is necessary for the EU to govern enlargement in a way that both upgrades national economies and fosters more equal social consequences. Only by doing this can we ensure the future developmental and democratic resilience of an enlarged EU.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Union

Marvelous paper Visnja! My compliments!