Revolutions have been a frequent occurrence throughout European history, yet the way they have emerged has varied tremendously over time. Mark R. Beissinger explains how the increasing concentration of people in cities over the last century has changed the nature of rebellion.

The city of Kyiv experienced multiple revolutionary uprisings over the past 120 years. Over that time, the ways in which populations attempted to assert control from below over wayward rulers altered tremendously.

Take, for instance, the Revolution of 1905 in Kyiv. After waves of strikes and peasant unrest in the surrounding countryside, in October 1905 a crowd of 20,000 assembled on Duma Square (better known today as Maidan) and demanded the resignation of Tsar Nicholas II. After participants refused orders to disperse, mounted Cossacks charged the crowd. In the tumult that followed, 12 demonstrators and 10 soldiers died.

That same evening, pogroms unfolded against the city’s Jewish population, leaving another 47 dead and 400 wounded. A Soviet of Workers’ Deputies was established and, with an arsenal of revolvers, hunting guns and garden spades, began preparations for an armed uprising. Soldiers from the Kyiv garrison mutinied and paraded through the city, but troops loyal to the regime surrounded them and opened fire, killing 40 and wounding 200. The Kyiv Soviet then mounted its insurrection; it lasted four days before being crushed.

Contrast Kyiv in 1905 with Kyiv in 2004. By 2004 Kyiv was a major metropolitan centre of 2.5 million – over eight times its population in 1905. Whereas 78 percent of Ukraine’s population in 1905 consisted of peasants, by 2004 only 6 percent of its workforce was employed in agriculture, rendering peasant rebellion in the surrounding areas of Kyiv unthinkable. The Orange Revolution began when 200,000 citizens – ten times the number who participated in demonstrations on the same site a century before – descended on Maidan to protest electoral fraud.

In the ensuing days, the number of protesters climbed to almost a million. In 2004, no Cossacks charged the massive crowds. After initially contemplating a crackdown, the regime backed off – fearful of what might ensue were violence perpetrated against such an enormous gathering. In all, the unrest associated with the 1905 Revolution in Kyiv dragged on for several years and involved hundreds of deaths, with the revolutionary opposition losing. In 2004, after seventeen days of round-the-clock protest that paralysed the country, the authorities caved in. Only one person died during the Orange Revolution – apparently, of a heart attack.

The power of numbers

Many of the differences between Kyiv in 1905 and 2004 can be attributed to the effects of urbanisation. In 1900, 13 percent of the world’s population was urban, and 13 cities had more than a million inhabitants. By 2023, 57 percent of the world’s population was urban, with 578 cities having populations larger than a million. By the late twentieth century, the proliferation of large, resourced, and highly networked populations in close proximity to the state’s nerve centres of power altered the possibilities for making urban revolution through the power of numbers. Prior to 1985, 70 percent of revolutionary episodes in cities were armed. Since 1985, 73 percent of urban revolutions have been unarmed, relying on the power of numbers.

Accordingly, many fewer people are dying in revolutions and the risks of rebellion have declined. Urban revolutions based on the power of numbers have generally materialised against regimes that were more autocratic, personalist, repressive and corrupt than the regimes experiencing rural revolutions. As societies urbanised and people moved closer to centres of state power, the state came to matter more in people’s lives.

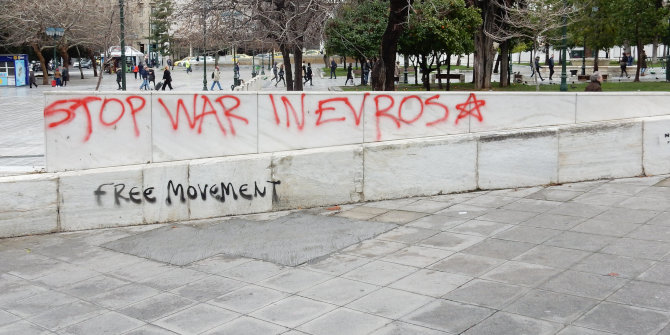

In cities, populations came into more regular contact with the state, including its unequalled capacities for predation and oppression. Across the world, urban dwellers have shown particular concern about issues of corruption. World Values surveys show, for instance, that city dwellers are much less likely to believe that it is justifiable to bribe an official than are rural inhabitants. Viewed in this light, it is not surprising that many of the grievances that permeate contemporary urban revolutions revolve around reclaiming the public sphere from corrupt, arbitrary, despotic government.

Unarmed rebellion in cities has a much higher rate of success than armed rebellion in cities, largely because cities are where the coercive power of the state is concentrated. Precisely the opposite is true in the countryside, where oppositions use distance and rough terrain to hide from state coercion, and armed rebellion remains one of the few ways that oppositions can exert leverage. But proximity to nerve centres of power heightens the risks of rebellion for both regimes and oppositions and transforms urban revolts into highly condensed affairs that unfold over days and weeks rather than years (as is true of rural rebellions).

This compression of time increases the likelihood of human error and renders the effects of errors more immediate and direct. In urban revolutions relying on the power of numbers, outcomes largely revolve around a struggle for control over public space in proximity to government nerve centres of power. The closer a revolt is able to come to these nerve centres, the more likely it is to leverage success. Thus, urban design, regulation of public space and spatial policing play central roles in regime strategies for countering these challenges.

A mixed record of post-revolutionary change

Unarmed revolutionary processes that concentrate hundreds of thousands in a matter of days or weeks necessarily draw on a wide variety of political forces. To maximise numbers in a concentrated period of time, these revolutions typically forge a broad negative coalition constructed in a makeshift manner, pulling in all who favour removal of the incumbent regime, irrespective of purpose or political beliefs.

They are more about what people are mobilising against than what they are mobilising for. Surveys show that corruption and economic issues are most frequently cited as the key grievances motivating participation; the desire for political freedoms is a motivating factor for a minority only. Accordingly, participants often display a weak commitment to democratic values in the wake of revolution.

Revolution by the numbers has a mixed record of post-revolutionary change. It tends to bring short-term improvements in political freedoms and civil liberties. But these achievements usually fall short of the average democracy and often deteriorate over time. And because they do not push aside the state but inherit it intact, corruption after revolution typically remains at high levels. Moreover, inequality tends to worsen and economic growth lags.

Because of these problems, and because they are built on hastily constructed, negative coalitions, they produce post-revolutionary governments that are fractious and unstable. In the Orange Revolution, for instance, squabbles over the redivision of property crippled the regime of Viktor Yushchenko, leading to the return of Viktor Yanukovych (whom Yushchenko had defeated in the revolution) to power through the ballot box within a few years.

In short, the lasting effects of revolution by the numbers are often ambiguous and uncertain. Sometimes, externally generated incentives (such as a foreign threat) can temper the fractiousness of revolutionary coalitions and push through necessary change. This has been a key difference between developments after Euromaidan compared with the Orange Revolution: ironically, Russia’s invasion of Crimea and meddling in the Donbas incited greater unity and created conditions for more significant reform.

This article draws on material in the author’s recent book, The Revolutionary City: Urbanization and the Global Transformation of Rebellion (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2022). The author will also be discussing his book at an LSE event on 8 February.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Julia Gaevskaya / Shutterstock.com