When judges assess difficult asylum cases, what guides their decision-making? Drawing on a new study, Katerina Glyniadaki shows how judges can experience a conflict between their role and their personal identity when dealing with “grey area” asylum cases.

The process of refugee asylum determination has been described by some as an “asylum lottery” or “refugee roulette”. Such characterisations are meant to denote the existing discrepancies in asylum recognition rates across different judges, organisations, regions and countries. Existing inconsistences in policy outcomes constitute a cause for concern, not only because they directly affect the lives of asylum seekers but also because they portray an asylum system that is potentially unfair and unreliable.

Various factors have been found to explain these inconsistencies, including the individual identities of asylum judges. While previous research has highlighted the ascribed identities of judges, for instance their gender, less attention has been dedicated to how asylum judges see themselves in this adjudication process and how their self-views shape their decisions. These perceived identities appear to be especially important for asylum cases which do not neatly fit codified law.

“Grey area” asylum cases

In a recent study I conducted during the so-called European refugee crisis of 2015-2017, I was able to interview lay and administrative judges in Germany and Greece, who make decisions both at the first and second instance of refugee asylum determination. We discussed which kinds of asylum cases are more likely to be handled differently by different judges and how judges come to decisions in what they see as more challenging or “grey area” cases. This category usually includes cases for which there is lack of adequate available evidence, making it nearly impossible to establish “the facts” of the case. In the words of one of the judges:

“Asylum seekers normally don’t have any documentation with them, or they don’t show it to the authorities […] You never know whether what they state is true, because they have an interest in telling a story which will get them asylum. […] On the one hand, you are not supposed to set unattainable evidence standards, and on the other hand you are constantly being lied to, and it is very difficult to say, yes, I believe this person. I am sure, I have no doubt that this person is telling the truth”. (Judge, Berlin)

As described here, there are often asylum cases for which the right decision is all but obvious. In such cases, the moral dimension of the dilemma becomes even more pronounced.

Identity conflicts for asylum judges

A common theme that emerged from the analysis of my interview data is that, in the face of moral dilemmas, asylum judges experience an identity conflict between their “role” identity as asylum judges and their own individual set of norms, values and preferences, or “person” identity.

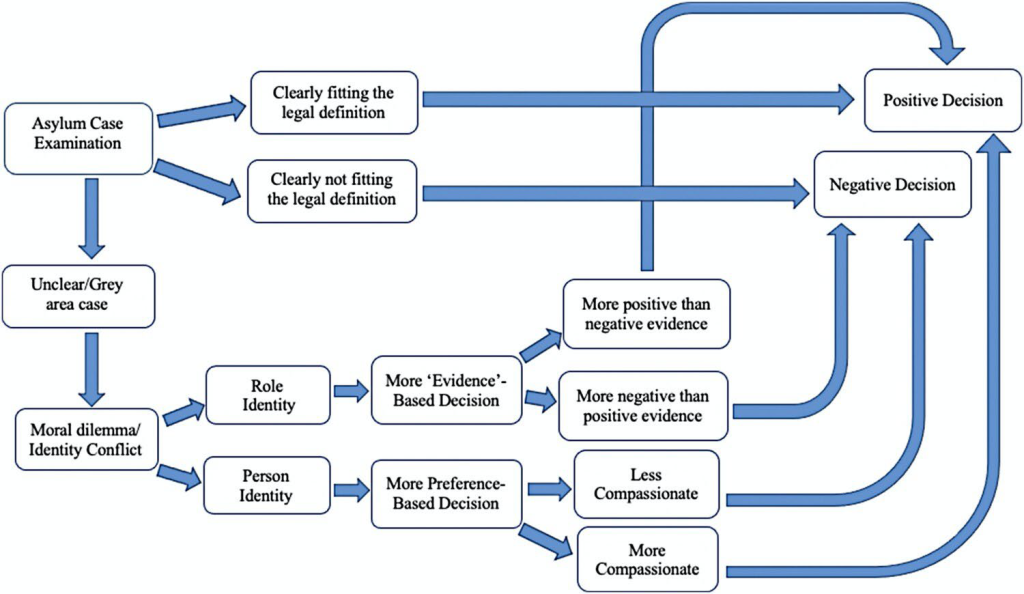

In turn, I argue in this article, their asylum decisions depend on which identity they consider more salient in the given context. If they view themselves primarily as bureaucrats who implement policy, then they filter out their personal opinion on the case under consideration and make a decision solely based on the available, however limited, evidence. By contrast, if their personal moral convictions take centre stage, their decision is more likely to be influenced by these. Figure 1 illustrates this decision-making mechanism.

Figure 1: Decision-making mechanism for asylum applications

Note: Compiled by the author.

To be clear, neither of these two avenues necessarily lead to positive or negative asylum outcomes. Rather, they describe how the judges’ decision-making process is identity-informed, whether influenced more by their role or person identities. The first quote below illustrates a role-based approach, while the second a person-based approach:

Your personal view may often be different from what is written on paper, or what was said [during the interview] … It’s just that your instinct is telling you, “What they’re telling me has been well-learned, but it is not their life” […] Often, you might be in that grey zone, where they tell a story that you cannot refute. So, there, I try to justify my decision based on the [available] information and not put my own opinion first. (Lay Judge, Athens)

Every time, when I am unsure, I really try to tell, if I am not sure that the risk of them being found and [persecuted] is higher than, you know, not. So, I just go with granting refugee protection […] So far, I’ve never been against the guidelines. What I have done is, if the guidelines keep it kind of open, then I try to interpret the guidelines differently… (Lay Judge, Berlin)

As it appears, some judges make an explicit effort to refrain from making decisions on the basis of their person-identity preferences (e.g. being compassionate towards asylum seekers), while others look for opportunities to interpret the existing guidelines in accordance with them.

In both scenarios, of course, the decision needs to be a lawful decision, supported by international sources and explained in black and white. Yet, generally judges have familiarity with a variety of relevant legal provisions, and they also have some discretion in terms of how they interpret and apply them. This means that their role identity is always of high importance in the given context, while the prioritisation of the person identity, meaning how much the personal interferes with the professional, may vary by individual.

Human decisions?

Overall, my research has brought to light how the human is intertwined with the bureaucrat in policy implementation, especially in such a highly politicised issue as that of migration management. The tension between professional and personal sides of asylum judges indicates that the person cannot be entirely disentangled from the professional. Some may still pose the question of whether such a complete separation would even be desirable. Achieving greater consistency in asylum outcomes is certainly not enough of a reason to claim so.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper at the Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Francesco Carucci / Shutterstock.com