The Greek debt crisis that began in 2009 has cast a long shadow over European integration. Drawing on a new study, Nicola Nones explains how the crisis became a “morality tale” that sharply divided EU member states.

The European sovereign debt crisis posed a profound threat to the fabric of the European project, with consequences reaching far beyond the conventional economic realm. According to several commentators, the crisis underscored the intricate social constructs inherent in credit and debt relationships, entwined with moral judgements about the character of the involved agents. This resulted in the media amplifying a “morality tale” that starkly divided “virtuous, hard-working” northern European nations on the one side, and unreliable and “spendthrift, lazy” southern European debtors on the other side.

In a new study, I examine whether and to what extent this moral discursive framing was systematic during the Greek crisis. I analyse more than 14,000 articles published in the Anglo-American and German financial press between 2004 and 2019, showing the extent to which Greece was described in negative moral language. I also document how, after the initial “shock” in autumn 2009, there was a noticeable increase in negative moral tone. Moreover, by most measures, this negative moral tone never completely reverted to pre-crisis levels, underlining how “sticky” economic narratives can become.

The moral dimensions of the Greek sovereign debt crisis

What prompted a moralistic characterisation of Greece during the economic crises? My reading of the academic literature and the content of mass media articles on the topic suggests three main channels.

The first and most general one concerns the historical connection between debt and morality. Throughout history, discussions on debt and credit relationships have consistently been intertwined with moral evaluations of the actors involved. This intricate connection has woven a moral Manichean narrative marked by two contrasting aspects: vice (for debtors) and virtue (for creditors). Notably, the German term “Schuld” continues to encompass dual meanings today: both debt and guilt. In this context, Greece is held accountable for living beyond its means at the expense of creditors, aligning with notions of guilt.

The second channel concerns the North/South (and creditors/debtors) cleavage specific to the Eurozone. When creditors insist on the repayment of debts, they may assert their actions are not driven by selfish material coercion but rather by fulfilling a “pedagogical role”. Within this discourse, the concept of the Mediterranean is juxtaposed with the “European”, portraying the former with traits such as indiscipline, extravagance, laziness, irresponsibility and corrupt tendencies.

Consequently, southern European countries, particularly Greece, are viewed as a potential threat to a union otherwise comprised of “good”, “civilised”, and “trained” northern European individuals. Unlike disciplined creditors, debtors have depleted the nation’s accumulated heritage to the detriment of future European generations.

Third, even among Mediterranean countries, Greece stands on its own. The “cradle” of western civilisation, with its people being considered the descendants of the classical Hellenes, Greece occupies a distinct position in the western cultural imagination. Parallels between ancient and modern Greeks during the crisis signalled Europe’s veneration of classical Greece and implicitly reaffirmed Europe’s good faith in honouring its moral debt to its ancestors. At the same time, they served to remind us how (modern) Greeks have failed to uphold the moral standards set by their ancestors.

The media and the morality tale

To empirically investigate the evolution of moral content in written texts about Greece, I assembled an original dataset of articles downloaded from the Factiva and LexisNexis databases for the period between 2004 and 2019. This timeframe encompasses the periods preceding, during and following the Greek crisis. The dataset focuses specifically on articles from three prominent financial daily newspapers: the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times, and the German publication Handelsblatt.

Having gathered articles based on predefined search criteria, I used two existing dictionaries – the General Harvard Inquirer and the Moral Foundation Dictionary – along with a custom word list to assess positive and negative moral tone. Following the validation of the dictionary, I computed a moral sentiment score for each article, with lower scores indicating a rise in negative moral content.

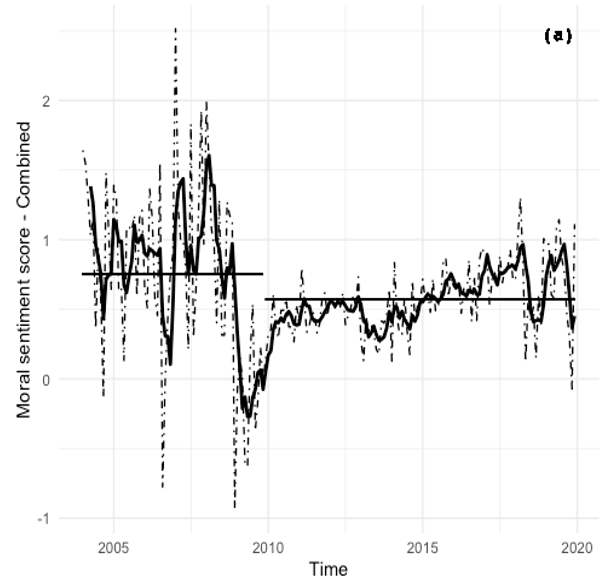

Figure 1: Average Moral sentiment scores (Financial Times and Wall Street Journal)

Note: The dashed line shows the raw series, i.e. the moral scores averaged across the two outlets over time. The thicker solid line shows the four months rolling average. Lower values indicate an increase in negative moral tone. The two horizontal lines show the average moral score pre- and post-crisis.

Figure 1 shows the results after aggregating each score at the monthly level. Clearly, at some point in the autumn of 2009, the moral sentiment score dropped. As anticipated, this coincided with the revelation of the crisis in October 2009, when the new Greek government disclosed a budget deficit of 12.7% of gross domestic product, twice as high as previously stated.

While a significant portion of the decline was swiftly offset, the moral score never fully rebounded to the pre-2009 level. Disaggregating the scores across the two financial papers, I calculated the average decrease in post-2009 moral tone to be 10.3% for the Wall Street Journal and 27.8% for the Financial Times. Repeating the analysis on the German newspaper Handelsblatt with the Moral Foundation Dictionary (the only dictionary available in German) revealed a similar, but more accentuated, pattern.

While the negative moral tone in the media lasted beyond the crisis itself, my analysis revealed one surprising finding. Against expectations, there is no evidence that the financial press framed the last and most acute phase of the Greek crisis in 2015 in increasingly moral terms. Overall, the empirical findings by and large vindicate the views expressed by several commentators, pundits and scholars regarding the moral framing of the Greek crisis, albeit not during the final phase of the Greek crisis itself.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper in European Union Politics

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: conejota / Shutterstock.com