The European Parliament election in Portugal will come just a few months after the 2024 Portuguese legislative election. On the fiftieth anniversary of Portugal’s Carnation Revolution, Lea Heyne and Luca Manucci examine the impact increased polarisation is having on the country’s politics and ask whether 25 April will continue to represent a unitary symbol of national identity.

This article is part of a series on the 2024 European Parliament elections. The EUROPP blog will also be co-hosting a panel discussion on the elections at LSE on 6 June.

In the last few months, Portugal has been shaken by political turmoil. In November 2023, socialist Prime Minister António Costa resigned because of a corruption scandal, the government fell, and President Marcelo Rebelo de Sousa called a snap election that was won by the right, interrupting nine consecutive years of socialist governments.

The right-wing coalition Democratic Alliance (Alianca Democratica – AD), formed by the Social Democratic Party (Partido Social Democrata – PSD) and the Social Democratic Centre (Centro Democrático e Social – CDS), narrowly won the elections in March 2024 with 28.8%, against 28.0% for the Socialist Party (Partido Socialista – PS).

No party, however, won an absolute majority, and the populist radical right party Chega (which means “enough”) confirmed itself as the third biggest party and showed that in the year of the 50th anniversary of the Carnation Revolution (the anniversary is celebrated on 25 April) so-called Iberian exceptionalism is definitely over.

These developments are in line with the general context of the 2024 European elections, with the populist radical right continuing to have momentum after winning already in 2014 and 2019. With over 18% of the votes gained at the March elections this year, Chega’s leader, André Ventura, has proclaimed the end of bipartisanship.

Chega wants to be the third pole and revolutionise the party system born out of the Revolution of 1974. We do not yet know if this prophecy will come true, but we do know that Portuguese voters show high levels of affective polarisation, which measures the distance between how much citizens like their own party and how much they hate other parties.

Affective polarisation in Portugal

Affective polarisation is important because it can undermine democratic functions and pluralistic norms and is associated with low social and institutional trust, as well as a democratic backlash. However, it can have positive effects, such as motivating political involvement, mobilisation, and increased participation. The 2024 elections in Portugal show that an increasingly polarised country went to the polls, with the highest turnout since 1995.

We have looked at the evolution of affective polarisation in Portugal since 2015 to observe the effects of the left-wing coalition (geringonça in Portuguese, meaning ramshackle) that ruled between 2015 and 2019, as well as the effect of Chega’s growing electoral success. The aim is to understand how Portuguese politics is evolving, and what consequences affective polarisation may have in the long term and at the next European elections.

Using survey questions, we can assess how supporters of each party evaluate their own party, as well as all the other parties, thus deriving the levels of affective polarisation. Then we grouped all the parties into ideological blocs to observe how affective polarisation is evolving between and within ideological blocs. On the one hand, the left bloc is composed of PS, Livre, Left Bloc (Bloco de Esquerda – BE) and the Portuguese Communist Party (Partido Comunista Português – PCP). The right, on the other hand, is composed of PSD, CDS, Liberal Iniciative (Iniciativa Liberal – IL) and Chega.

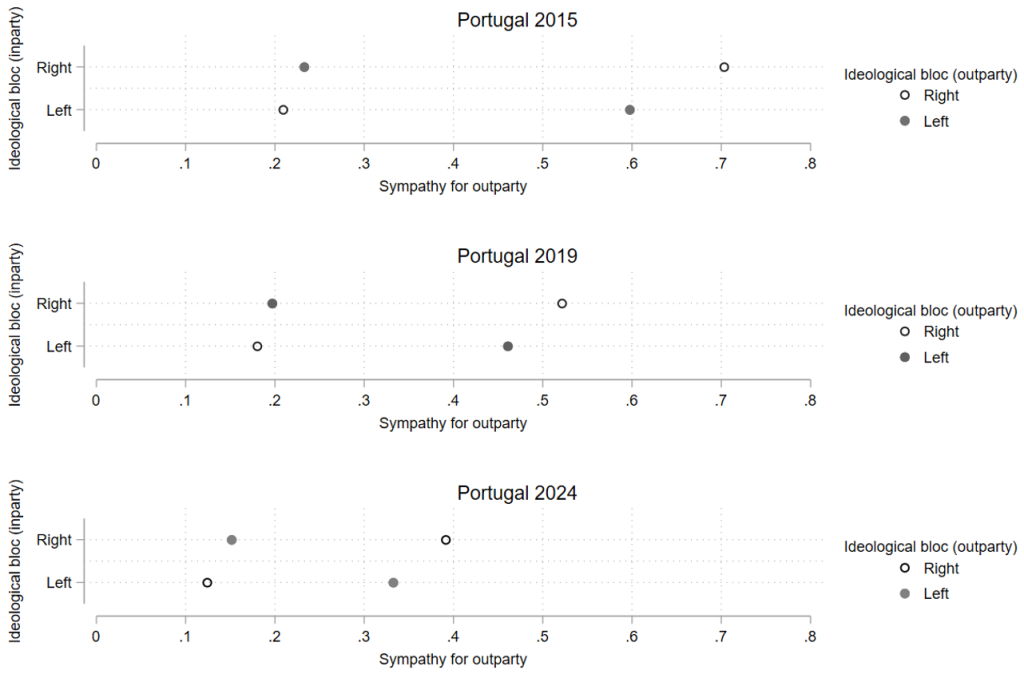

Figure 1: Sympathy within and between ideological blocs, 2015-2024

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Figure 1 shows how respondents from each ideological bloc, rate – on average – all the parties in their own bloc and all the parties in the opposite bloc. Between 2015 and 2024, the “hatred” of the right towards the left and vice versa, has increased. Right-wing and left-wing voters dislike each other more and more, and the two blocs are drifting further apart.

Moreover, the 2019 and especially the 2024 elections show growing antipathy within the ideological blocs. This means that respondents on the left are increasingly antipathetic towards other left-wing parties that are not their preferred party, and respondents on the right are increasingly antipathetic towards other right-wing parties.

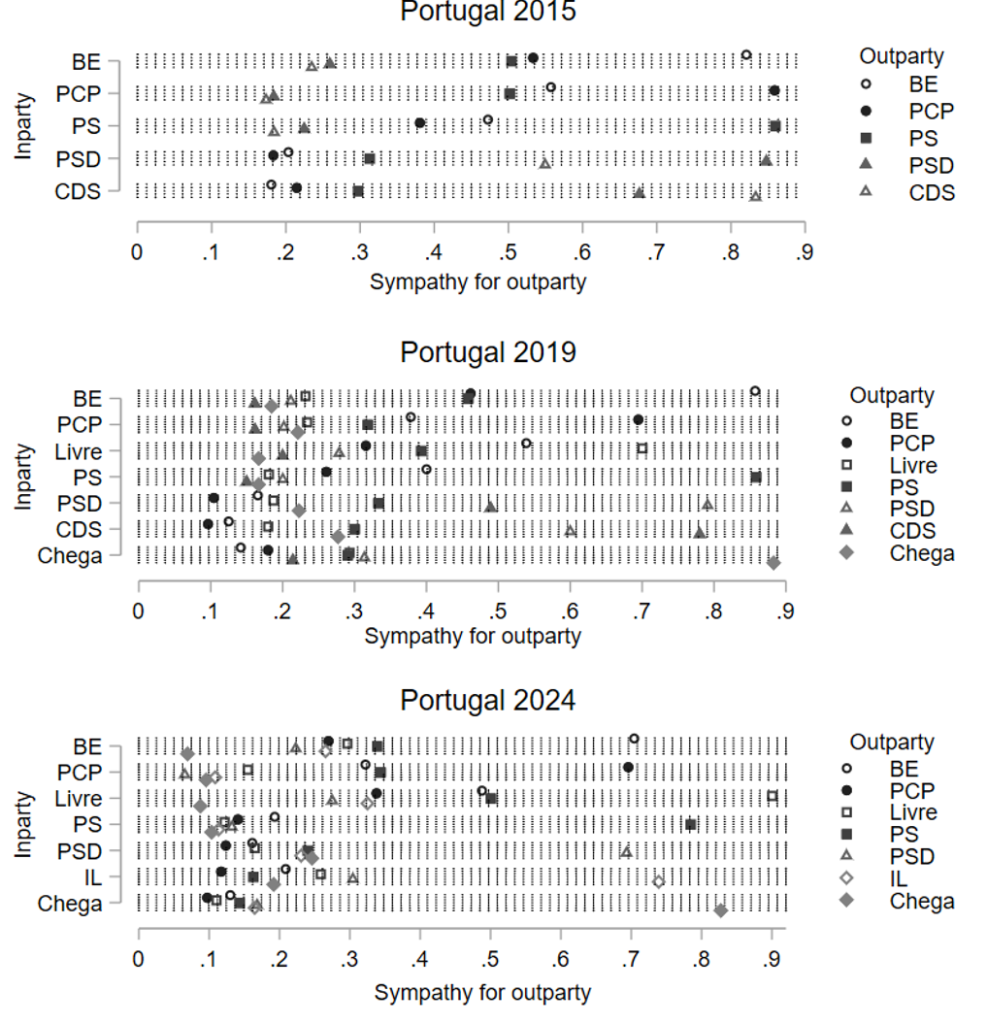

Figure 2: Sympathy within and between parties, 2015-2024

Source: Compiled by the authors.

To better understand these trends, we analysed the data for each party. Figure 2 shows how sympathisers of each political party rate, on average, all the other political parties as well as their own. In 2019, new parties such as Chega, IL, and Livre entered the Assembly of the Republic, introducing some changes.

First, hatred between ideological groups, especially the hatred of right-wing supporters towards left-wing parties, increased. Second, the divide between the respondents’ favourite party and all the other parties has grown. In 2024, antipathy between parties is at an unprecedented level, with supporters of each party showing high levels of antipathy towards at least one, but often several, other parties. The three parties with the most votes (PS, PSD and Chega) are the ones with the most polarised supporters.

An end to the two-party system?

The increasing levels of affective polarisation both between the left and right blocs and within each bloc could signal the end of a two-party system and the beginning of a three-party system made up of the mainstream right, the radical right and the left (the latter two united by their strong Euroscepticism).

If the left continues to polarise, with PS voters increasingly distancing themselves from BE and PCP voters, and BE and PCP voters liking each other less and less, this could even result in a four-party system. This means that, in addition to the classic left-right divide, there would be a new divide separating the traditional parties that represent the continuity of the Portuguese political system from the newer parties that mobilise dissatisfied voters through populist rhetoric.

In this scenario of fragmentation, the PS and PSD may have no choice but to start thinking about the possibility of implementing a grand coalition like in Germany, where the centre-left and centre-right form an alliance to govern together, thus excluding the radical parties. There are alternatives, but all of them involve the risk of very unstable governments and frequent elections, as in Spain. Is trust in the Portuguese political system irretrievably broken? In this scenario, will 25 April continue to represent a unitary symbol of national identity?

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: rarrarorro / Shutterstock.com