The rise of populism has been described as the “revenge of the places that don’t matter”. But how does “place” shape support for populism? Drawing on a new study, Kai Arzheimer and Theresa Bernemann show that the geography of right-wing populism is not just about where people live but about how they relate to their surroundings and each other.

In recent years, the rise of the populist radical right has sparked intense debate and concern across the globe. This political shift has prompted researchers to delve into the myriad factors that fuel such sentiments. Among these, the concept of “place” has emerged as a pivotal yet complex element in understanding (right-wing) populism.

But what exactly does “place” mean in this context, and how does it influence political attitudes towards nativism, right-wing authoritarianism, and populism? At its core, “place” encompasses more than just a physical location on a map. It embodies a range of socio-political and cultural dimensions that can significantly impact the political views of individuals.

In a recent study, we identify four key aspects of “place” that are crucial in shaping populist radical-right attitudes. The first is “place-related attitudes”. This includes localism, or the feeling of belonging to one’s locality, and place resentment, which refers to feelings of one’s locality being left behind or neglected by the broader society. Second, there are “place-specific living conditions”. These are the economic, social, and environmental conditions of a given place that can influence residents’ political perspectives.

Third, there is the “socio-demographic composition” of a place. The makeup of a local community, including factors like age, income, education, and ethnic background, plays a role in shaping political attitudes. Finally, there are “unique characteristics”. Every place has its own history and culture, which can contribute to a sense of identity and belonging among its inhabitants.

A closer look at Germany

To understand how these aspects of “place” influence populist radical-right sentiment, we turned our attention to Germany – a country with a complicated and often dark history, diverse regional identities and a highly decentralised, federal political system. Utilising detailed geocoded survey data collected just before the 2017 general election, we uncovered several intriguing findings.

First, we observed significant spatial variation in populist radical-right attitudes across Germany, with certain areas (such as swathes of Saxony and Thuringia as well as parts of Bavaria) showing noticeable clustering. This suggests that the sentiment towards the radical right is not uniformly distributed but rather concentrated in specific regions.

Second, the socio-demographic composition of a place, along with feelings of place resentment, emerged as strong predictors of populist radical-right sentiment. These factors significantly influence how individuals in different areas perceive and align with populist radical-right ideologies. Similar patterns of (self-)sorting and geographical polarisation have also been observed in the United States.

Third, and contrary to our expectations, localism – defined as the feeling of belonging to one’s locality – had a weaker effect on populist radical-right attitudes than anticipated. Our analysis also revealed no significant interaction between localism and place resentment, indicating that these factors operate independently in shaping political attitudes.

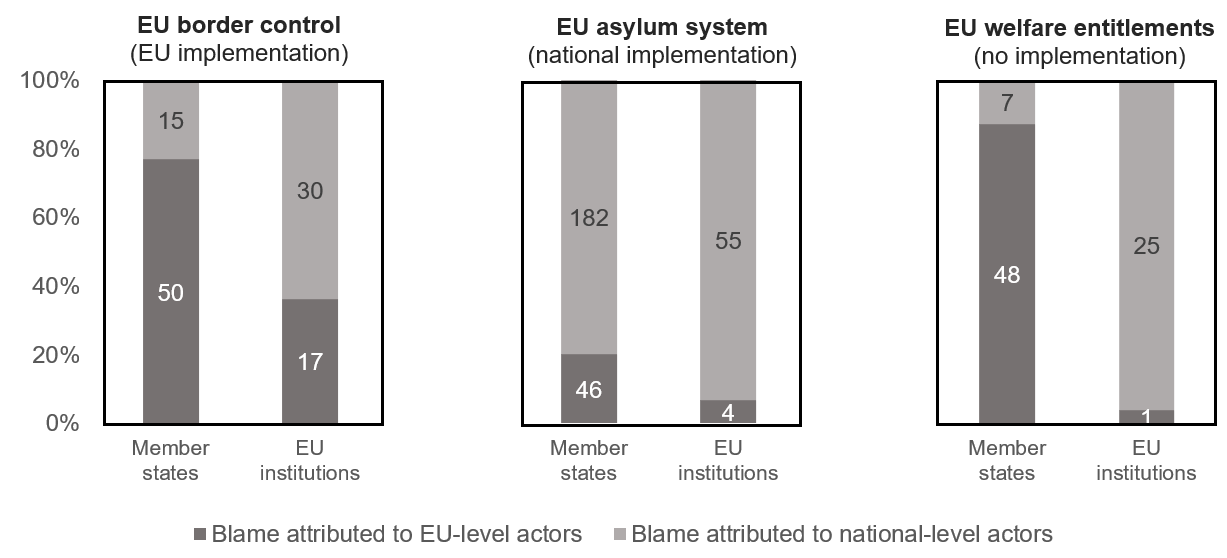

Figure: Cluster maps of populist radical-right attitudes, localism and place resentment in Germany

Note: County level data. For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the European Political Science Review.

Fourth, the unique culture and history of specific locations did not directly impact populist radical-right attitudes in our study. However, being located in the former GDR (East Germany) still plays a substantial role in shaping political attitudes, underscoring the lasting influence of historical and geopolitical contexts on contemporary political landscapes.

Finally, place-specific conditions, such as economic deprivation, demographic decline, migration, and rurality, were found to have minimal or weak effects on populist radical-right sentiment. This highlights the complexity of factors influencing political attitudes and the need for a nuanced understanding of how “place” shapes political sentiments. Our findings thus contribute to the broader discourse on the geography of radical-right populism, offering valuable insights into how “place” influences right-wing political attitudes in Germany.

Implications and reflections

Our results challenge the notion that “places that don’t matter” – areas often overlooked or marginalised – are hotbeds of populist radical-right sentiment solely due to economic or demographic factors. Instead, a complex interplay of local identity, socio-demographic composition and historical context shapes political attitudes. This underscores the importance of recognising and addressing the unique needs and concerns of different communities.

The geography of right-wing populism is not just about where people live but how they relate to their surroundings and each other. As we navigate the challenges of rising populism, understanding the nuanced role of “place” can help us foster more inclusive and responsive political dialogues.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the European Political Science Review

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Juergen Nowak / Shutterstock.com