In 2014, the recognised Ukrainian territory of Crimea was annexed by Russia. Here, Eleanor Knott reflects on the effect of secession in the region and its impact on her research.

There’s a strange feeling that comes with finishing something that has been a bit painful. Writing a thesis is supposed to be hard, but working with data that I gathered in Crimea in 2012 and 2013—when the idea of secession, annexation or even the end of the Yanukovych/Party of Regions regime seemed farcical—has felt particularly acerbic.

This pales in comparison to the suffering of those I know in Crimea, whose peninsula was “stolen” by Russia. This isn’t the typical story you see about Crimea where media reports generally repeat an argument that secession was a historical inevitability that never happened and/or would be the same result even if a free and fair referendum had taken place. This is something I refute, and continue to refute not least because of the people I know there that don’t fit into our neat boxes of ethnic Russian or ethnic Ukrainian. Before 2014, they were just Ukrainian. And while I acknowledge that ethnic minorities, Crimean Tatars and Ukrainian speakers, have faced increased, and horrendous, discrimination since annexation, the story of the majority is rarely discussed: everyday disasters of banking, property rights, passports, Russia’s ban of methadone for (former) heroin users, human rights, democracy, and more existential disasters, of belonging and identity.

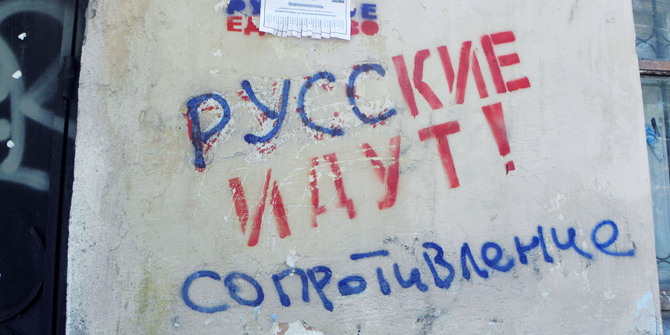

But the discomfort of working on Crimea is something I’ve had to fight since February 2014. At first I panicked: how could I write about something that had changed so quickly? My thesis was based on territorial stability. I had assumed, presumed, that 23 years of stability vis-a-vis Russia and Ukraine, and Russia more generally vis-a-vis ethnic Russians, was a reasonable lesson for the future. Most post-Soviet scholars had predicted the same: Russia was faced with a commitment problem that it was unwilling to overcome. As masked men emerged in Simferopol, storming Crimea’s parliament, removing the Ukrainian flag from the Council of Minister’s building, replacing it with a Russia flag, and patrolled with automatic weaponry the same streets in Simferopol that I’d walked 8 months previously, my faith dissipated.

After this I thought I was going a bit mad: my argument was that identity in Crimea was much more complex than mutually exclusive census categories of “ethnic Russian” and “ethnic Ukrainian”, and where being “ethnically Russian” did not determine support of Russia, let alone support for Putin. I felt like I had collected data, and was making arguments based on my analysis of this data, that completely contravened how others approached the peninsula, as if of course the Russian majority favoured Russia, and separatism, rather than Ukraine. Including the minority of respondents who identified with Russia, and felt discriminated by Ukraine, none of my respondents supported secession from Ukraine: it just seemed unthinkable, if not farcical. Their gripe, regardless of identity, was with how Crimea was governed by Kyiv, and the Party of Regions, not with supporting secession.

I then read an article by Julia Ioffe, covering post-Soviet identity debates in Donetsk, a region that would quickly spiral much more out of control than Crimea, and it resonated distinctly with identity debates present in Crimea:

“The younger a citizen of Donetsk, the more likely she is to view herself as Ukrainian. The older she is, the more likely she is to identify as Russian. And this is the crux of it all: What we are seeing today is the reverberation of what happened more than 20 years ago. This is still the long post-Soviet transition. And this is what it’s like to wander in the desert, waiting for the old generation to die off.”

So now I just tell the story that I believe the data I collected speaks to: highly complex and fractured notions of identity in Crimea, that problematise the supposed cohesive idea of an ethnic Russian majority and the idea that identifying as Russian is analogous to identifying with Russia, as a society, state and, much less, regime. Similarly, I argue Crimea was not a region of Russian passportization: everyone I interviewed found Russian citizenship inaccessible and most found it undesirable. The small majority who wanted Russian citizenship/passports but couldn’t access them were the discriminated minority, who thought Russian citizenship would increase their leverage against Ukraine; but most I spoke to did not feel discriminated within Crimea by Ukraine. Nor was Crimea a region populated by those endorsing separatism, at least among those I met, because individuals supported Ukraine and/or supported peace. Neither they, nor I, thought Russia wanted Crimea or conflict.

Now I tell a ‘history of the past’ because for those I interviewed, many of whom fall into the chasm of the Russian ‘majority’ that are presumed as endorsing annexation, it’s the least and most I can do.

Eleanor Knott is a PhD candidate (expected 2015) in political science at the Department of Government, London School of Economics and Political Science. Her thesis explores Romanian and Russian kin-state policies in Moldova and Crimea from a bottom-up perspective, using the approach of everyday nationalism. Her broader research interests include studying questions of political science in the post-Soviet region from the bottom-up, using techniques of political ethnography, including identification, citizenship and education policy, to study state-society relations from an international perspective. She has published in East European Politics and Societies and Social Science Quarterly. This article was origingally posted on Eleanor’s blog. You can also follow Eleanor on twitter.

Eleanor Knott is a PhD candidate (expected 2015) in political science at the Department of Government, London School of Economics and Political Science. Her thesis explores Romanian and Russian kin-state policies in Moldova and Crimea from a bottom-up perspective, using the approach of everyday nationalism. Her broader research interests include studying questions of political science in the post-Soviet region from the bottom-up, using techniques of political ethnography, including identification, citizenship and education policy, to study state-society relations from an international perspective. She has published in East European Politics and Societies and Social Science Quarterly. This article was origingally posted on Eleanor’s blog. You can also follow Eleanor on twitter.