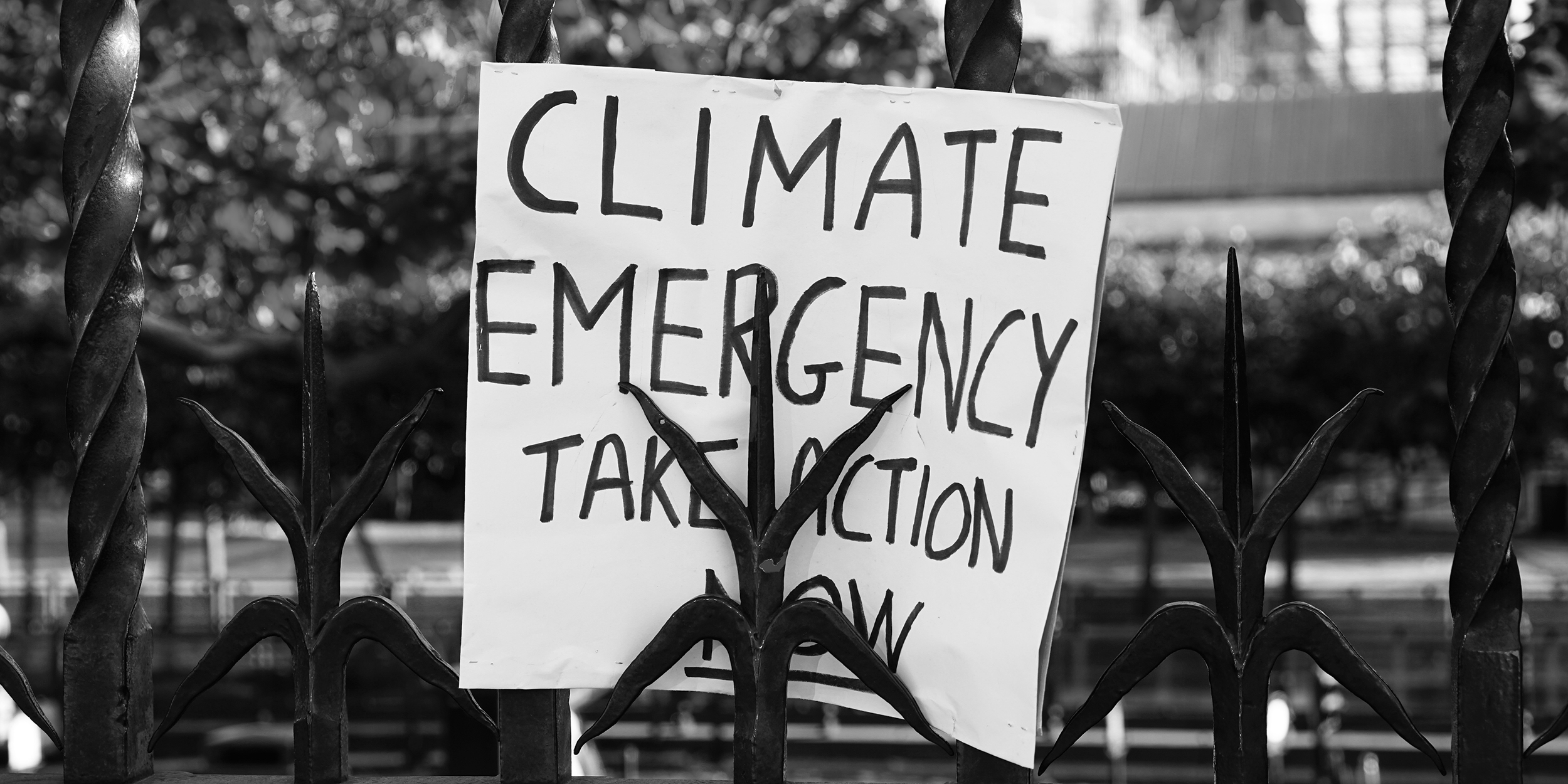

With COP26 approaching, our students reflect on the response of governments to the climate crisis.

“While change is happening, it is too slow”

“While change is happening, it is too slow”

For the duration of my life, the majority popular belief has been anti-fossil fuel. A clear moral binary has emerged in society, with oil and gas as the villain, and environmentalism as the hero. This has been re-enforced culturally, in TV, movies and social media, and in school – from primary, secondary, and finally into university. Everywhere I look, broadly speaking, we condemn climate change and embrace the advance toward net zero.

But despite this moral consensus, the status quo is largely unchanged. Over the course of the last year, the number of offshore oil rigs in the US has doubled, and the Paris Climate Accord, the source of so much optimism in years past, seems incapable of holding nations to account. While change is happening, it is too slow, marred by private interests and a powerful conservative majority that continues to deny the truth: we are on the edge of disaster.

Is this the fault of the government? I think so. These are democracies, created to implement our wants and care for our needs. In falling short of this, they have failed in their mandate to serve and uphold the majority will – instead succumbing to the pressure of profit-driven corporations and fringe stakeholders. Beyond the crime of neglecting climate change, governments are failing to safeguard the integrity of democratic life. If this does not change, our political ideals stretching back centuries risk being fatally undermined.

Tom Charley is a 20-year-old second year history and politics student in the LSE Department of Government, with an interest in foreign affairs, history, politics and journalism.

‘It’s difficult to remain hopeful but the urgency of the situation should finally make politicians take action”

‘It’s difficult to remain hopeful but the urgency of the situation should finally make politicians take action”

The above quote is from Greta Thunberg, the world famous teenage environmental activist who has become a leading figure in the climate debate. While her experience, trajectory and outlook on all things environmentalism is particularly inspiring, I can’t help but feel disappointed that we are praising a phenomenon which is essentially a result of catastrophic policy failure.

While activism has proven to be an effective means of influencing policy change, we cannot deny that protesting in favour of something which should have been, according to many, first on our policymakers’ agendas can never be acceptable. Governments have yet to realise that old patterns cannot be broken with old ways. What they have achieved is only buying time for an unsustainable system to briefly flourish, until a complete breakdown is reached.

It is difficult to remain hopeful in light of the upcoming COP26, seeing as a pause in action has also been conveniently blamed on the ongoing pandemic. However, I place faith in the urgency of the situation, with the tipping point of irreversible environmental destruction edging ever closer, to finally make politicians feel as if “the house is on fire. Because it is”.

Emily Petrou is a first year BSc Politics student in the LSE Department of Government from Nicosia, Cyprus. She has a passionate interest in sustainability, society and post-colonialism, as well as intersectional gender and racial issues.

“In a system dominated by short-term policy, there is little appetite to adequately address climate change.”

“In a system dominated by short-term policy, there is little appetite to adequately address climate change.”

The simple answer is no. The nature of policy-making as increasingly results driven means there is no need for governments to make much more than superficial policy advances on climate change. Policy-making is driven by the need to gain support from large target groups, now more than ever, and polls show that the vast majority of the electorate has little interest in addressing climate change, instead focusing on traditional issues, such as immigration and the economy.

Whilst climate change is a salient issue among younger voters, they are the least likely to vote in elections and so manifestos do not focus on meeting their demands. The sheer estimated cost of decarbonising the economy is enough to disincentivise policymakers. In a system dominated by short-term policy, there is little appetite to incur billions with little tangible reward. Instead, nominal measures that present an appealing soundbite are chosen.

Globalisation also ensures responsibility for climate change remains diffuse. It is easy for leaders in prosperous nations, such as the UK and US, to blame industrial nations such as India and China for the production of greenhouse gases. However, the symbiotic role wealthier nations play in this pollution, through consumerism and a demand for lower prices, is rarely ever addressed.

Until such a time where either younger voters become kingmakers in politics or other groups are more interested in addressing climate change, it is unlikely that any government will feel the need to adequately address the threats posed by climate change.

Daniel Barnett is a first-year undergraduate student studying Politics and International Relations at LSE.

“Australia’s self-destructive love affair with coal contravenes their existential self-interest”

“Australia’s self-destructive love affair with coal contravenes their existential self-interest”

Governments are stalling critical reform because the effects of the climate crisis are most significantly felt in poorer countries, those with less bargaining power and diplomatic capacities. Wealthy countries, who are overwhelmingly responsible for emissions, can turn a blind eye because they are geographically less vulnerable. The exception is the ‘lucky country’; Australia.

The very factors that accounted for Australia’s luckiness are now expediting its demise. Expansive coastlines and arid climate amplify warming, and an abundance of coal, an especially carbonic fossil fuel, has provided a cheap and dirty energy source.

The conservative government continues to finance coal, with no provisions for renewable energy, which over time will soon cause drought, fires, and floods in Australia and inundate its poorer Micronesian neighbours. The foreign minister of the Marshall Islands argues that this amounts to genocide.

Through a carbon accounting loophole from Kyoto, Australia has consistently shirked its already modest Paris commitments. Though experts say Australia ought to cut emissions by 47%, Australia has only agreed to 26%, yet is currently on track for merely 7%.

Australia’s leadership has not indicated that it takes the agreements seriously, and has already threatened withdrawal from Paris. The PM expressed indifference towards attending COP26, displaying total disregard for accountability, ‘hold(ing) a diplomatic gun to the head (of the developing world)’ thanks to the absence of effective enforcement mechanisms by the UN.

Australia’s Conservative-Nationalist coalition will continue to annihilate its atmosphere with coal, and the ineffectual soft-powers-that-be can do little as Australia continues to contravene their existential self-interest.

Honour Astill is a first year BSc in Politics student in the LSE Department of Government, interested in climate policy and regime shifts.

“There is no normal to return to, we must ask for something new.”

“There is no normal to return to, we must ask for something new.”

‘Everything changes, everything flows. You can never step in the same river twice’, wrote Heraclitus long before we began burning fossil fuels. Change is not necessarily good or bad, but it is inevitable. When it comes to climate, crisis is more precise than change: it better reflects the seriousness of the overall situation.

Climate crisis has achieved popular usage. So, we should enquire as to whether it can fruitfully be compared to other crises: namely, the 2008 financial crisis and the coronavirus crisis.

The response to the 2008 financial crisis was methodologically radical, but substantively conservative: as William Davies wrote, ‘Crucially the nature of the rescue… meant that debt obligations were held up at all costs’. If the financial crisis provoked a conservative response, ‘The immediate economic policy response to the coronavirus shock drew directly on the lessons of 2008’, as Adam Tooze observed.

Both the coronavirus and the financial crisis are historically localised, and so we can make sense of the clamour for a ‘return to normality’. It is the normality of 2007 or 2019 that was being called for. However, the climate crisis has been in motion since the industrial revolution. If climate policy aims to ‘stop change’, then what is it trying to preserve? There is no normal to return to. If both 2008 and coronavirus have been disruptions to continuity, the climate crisis is not a disruption: it is the continuity. Conservation is not the goal: we must ask for something new.

Ben Binks is a first-year undergraduate student in Politics and Philosophy at LSE. He is interested in the history of political ideas, and the future of left politics.

“At this point, even 99% commitment is not enough”

“At this point, even 99% commitment is not enough”

With the ongoing COVID-19 Pandemic, climate change has been somewhat neglected in national agendas. 2021 is a crucial year to shift governments’ focus towards this global issue which, if not tackled, will accelerate a possible sixth mass extinction. Although multilateral events are being held on every scale to alarm and urge governments to act, most notably the upcoming COP-26, too many state leaders in this world have yet to grasp the devastating outcomes of not tackling climate change. Instead, many continue to pursue policies which are exacerbating the problem.

On the whole, most governments have done relatively little to reduce carbon emissions, invest in non-renewable energies, or provide educational programs to support environmentally responsible and sustainable practices. Even sadder is the fact that the pressure against climate change has come significantly more from non-state actors.

Governments need to shift their mindsets quickly and embrace the idea that investing in environmentally sustainable practices is a lot cheaper and economically beneficial in the long run. By understanding so, they could start to create more ambitious emissions targets, educate people that the internet is the world’s largest coal-powered machine that contributes significantly to climate change (especially during lockdowns), economically incentivise environmentally sustainable business practices, and, most importantly, holistically integrate their national agendas with tackling climate change.

Currently, the world is set to exceed and even double the 1.5 degrees temperature threshold in this lifetime. At this rate, even a 99% commitment to tackling climate change is not enough, governments need to make every possible effort in order to avoid disaster.

Moses H. Siregar is a first-year Politics and International Relations student in the LSE Department of Government. His study interests include climate change and green politics, global trade, and socio-economic inequality in developing countries.

Note: this article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Department of Government, nor of the London School of Economics.