Greece may be about to get some debt relief, although there is still resistance to the idea. This column argues that the ECB has been providing other Eurozone countries with debt relief since early 2015 through its programme of quantitative easing. The reason given for excluding Greece from the QE programme – the ‘quality’ of its government bonds – can easily be overcome if the political will exists to do so. It is time to start treating a country struggling under the burden of immense debt in the same way as the other Eurozone countries are treated.

It looks like Greece may get some debt relief.1 There is as yet no certainty about this because some German politicians continue to conduct rear-guard battles to prevent it.

What is certain, however, is that all Eurozone countries, with the exception of Greece, have been enjoying debt relief since early 2015. That may seem surprising to the outsider. Some explanation is necessary here.

QE as EZ debt relief: But not for Greece

As part of its new policy of ‘quantitative easing’ (QE), the ECB has been buying government bonds of the Eurozone countries since March 2015. Since the start of this new policy, the ECB has bought about €645 billion in government bonds. And it has announced that it will continue to do so, at an accelerated monthly rate, until at least March 2017 (Draghi and Constâncio 2015). By then, it will have bought an estimated €1,500 billion of government bonds. The ECB’s intention is to pump money in the economy. In so doing, it hopes to lift the Eurozone economy out of stagnation.

I have no problems with this. On the contrary, I have been an advocate of such a policy (De Grauwe and Ji 2015). What I do have problems with is the fact that Greece is excluded from this QE programme. The ECB does not buy Greek government bonds. As a result, the ECB excludes Greece from the debt relief that it grants to the other countries of the Eurozone.

How is this possible? When the ECB buys government bonds from a Eurozone country, it is as if these bonds cease to exist. Although the bonds remain on the balance sheet of the ECB (in fact, most of these are recorded on the balance sheets of the national central banks), they have no economic significance anymore. Each national treasury will pay interest on these bonds, but the central banks will refund these interest payments at the end of the year to the same national treasuries. This means that as long as the government bonds remain on the balance sheets of the national central banks, the national governments do not pay interest anymore on the part of its debt held on the books of the central bank. All these governments enjoy debt relief.

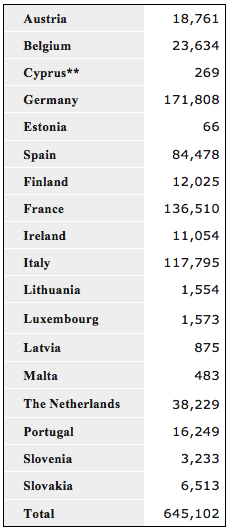

How large is the debt relief enjoyed by the governments of the Eurozone? Table 1 gives the answer. It shows the cumulative purchases of government bonds by the ECB since March 2015 until the end of April 2016. As long as these bonds are held on the balance sheets of the ECB or the national central banks, governments do not have to pay interest on these bonds. The ECB has announced that when these bonds come to maturity, it will buy an equivalent amount of bonds in the secondary market. We observe that the total debt relief granted by the ECB until now (April 2016) to the Eurozone countries amounts to €645 billion. We also note the absence of Greece and the fact that the greatest adversary of debt relief for Greece, Germany, enjoys the largest debt relief from the ECB.

The announcement of the ECB that it will continue its QE programme until at least March 2017 and that it will accelerate its monthly purchases (from €60 billion to €80 billion a month) implies that the debt relief that will have been granted in March 2017 will have more than doubled compared to the figures in Table 1. For many countries, this will amount to debt relief of more than 10% of GDP.

Table 1 Cumulative purchases of government bonds (end of April 2016)

(million euros)

Source: ECB (for details on the ECB’s asset purchase programmes, see https://www.ecb.europa.eu/mopo/implement/omt/html/index.en.html).

Greece is excluded from the QE programme, and thus from the debt relief that arises as a result of this programme. The ECB gives a technical reason for this exclusion: Greek government bonds do not meet the quality criteria required by the ECB in the framework of its QE programme. But that is extremely paradoxical. Countries that have issued ‘quality’ bonds enjoy debt relief. As soon as they are on the central banks’ balance sheets, these bonds cease to exist from an economic point of view. It is as if they are thrown in the dustbin. Thus this whole operation amounts to throwing the good bonds in the dustbin, but not the bad bonds.

The exclusion of Greece is not the result of some unsurmountable technical problem. These technical problems can easily be overcome when the political will exists to do so. The exclusion of Greece is the result of a political decision that aims at punishing a country that has misbehaved.

It is time that the discrimination against Greece stops and that a country struggling under the burden of immense debt is treated in the same way as the other Eurozone countries that have been enjoying silent debt relief organised by the ECB.

References

De Grauwe, P. and Y. Ji (2015), “Quantitative easing in the Eurozone: It’s possible without fiscal transfers”, VoxEu.org, 15 January.

Draghi, M. and V. Constâncio (2015), “Introductory statement to the press conference (with Q&A)”, 3 December.

Endnotes

[1] See http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/be2a621a-161a-11e6-b8d5-4c1fcdbe169f.html#axzz48TPG1cQl.

The article was first published on VOX, CEPR’s Policy Portal on May 13th 2016.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of Greece@LSE, the Hellenic Observatory or the London School of Economics.

I question the basic premise of this article, namely that “when the ECB buys government bonds from a Eurozone country, it is as if these bonds cease to exist” and that “these bonds have no economic significance any more”.

If such bonds indeed ceased to exist, no issuing country would need to worry about paying them when their maturity comes up. But they do have to pay them when their maturity comes up.

Yes, the issuing country must continue to pay interest on these bonds but, no, it is not clear how they can get that full interest payment back from the ECB at year’s end. The ECB distributes dividends out of its “net income” to its member countries. “Net income” and “gross interest income” are two totally different items. The ECB will always have gross interest income but it may not always have net income for the distribution of dividends. In fact, The ECB could even incur substantial net losses in any given year making the distribution of dividends impossible.

I know that Greece has (or had) special agreements with the ECB where the ECB would make certain rebates/refunds to Greece such as revaluation profits incurred by the ECB on Greek bonds but I am not aware of any general rule of the ECB that, as parts of its QE program, it would refund interest received from countries to those countries’ treasuries.

I would appreciate clarification.

The ECB has announced that when the bonds come to maturity it will buy the equivalent amount of bonds of the same government to replace the bonds maturing. As long as these bonds remain on the balance sheet of the central bank they have no economic significance. See my paper in VoxEU: http://voxeu.org/article/quantitative-easing-eurozone-its-possible-without-fiscal-transfers

QE purchases increase the interest payments to the Eurosystem. The marginal costs of these operations are close to zero. As a result, the net income increases by the same amount as the gross interest income. This is redistributed to the issuing countries. Note also that most of the national government bonds (80%) are held on the balance sheets of the national central banks. Thus the interest revenues of the NCBs will be redistributed directly to the national treasuries.

Thank you for your clarifying response! I have also read your voxeu paper.

Personally, I do not share the old Krugman argument that “we owe our debt to ourselves” or, as you say in your paper, that purchased bonds “are just a claim of one branch of the public sector (the central bank) against another branch of the public sector (the government). These two branches should be consolidated into the public sector, and then it turns out that these claims and liabilities cancel out”. Such arguments ignore the issue of different pockets but I recognize that one could debate this forever. Many lenders have painfully found out that when they lend on the basis of consolidated statements, they are lending to a company which does not exist. At the end of the day it does make a difference whether the borrowing entity has its own cash flow or not. Conceptually the same applies to consolidating the public sector.

I was not aware of the ECB’s commitment to replenish maturing bonds. For that to take away the economic significance from the bonds, the ECB’s commitment would really have to be totally unconditional and without expiry. If they were totally honest, they should be buying Evergreen Bonds.

I understand your logic of zero-sum interest payments/receipts which assumes that every Euro of additional gross income of a central bank equals one Euro of additional dividend pay-out (because there are no marginal costs). That ignores the point that if and when central banks make losses, they generally don’t do that because operating costs exceed revenues. Instead, they report losses when they have to make significant revaluations or provisions for valuation losses (see the Swiss National Bank). Also, not every central banks fulfills the Finance Minister’s wishes for dividend pay-out (both, the Swiss National Bank as well as the Bundesbank are reducing they dividend pay-out capability significantly by making provisions for losses).

Incidentally, it should be borne in mind that while the ECB cannot go bankrupt, national central banks indeed can!

In terms of national accounts/budget, I am sure Greece will continue to record interest expense as long as they pay interest on their bonds regardless of who owns those bonds. Dividends received from the central bank are booked separately as revenues. This practice in and by itself underlines that there is a qualitative difference between expenses and revenues and one cannot create the impression like they are one and the same thing (even though in practice it may work out that way).

I have learned from you articles/comments and thank you for that. All I am saying is that while I can follow your logic, I am not quite sure that I am 100% convinced.