The 8th of March is International Women’s Day. On this occasion, we want to highlight how traditional gender norms and economic hardship jointly contribute to violence against women. Across the world, much of the abuse women experience comes from romantic partners and within what is meant to be a safe family environment. And, an important factor that has been found to increase the rates of domestic violence is economic downturns. Given Greece’s decade-long economic recession, and given also the primacy of family as a social institution, what is the state of domestic violence in today’s Greek context?

The effects of the Greek crisis have been indeed devastating for the Greek society. The total unemployment rate reached a record high of 27.5% in 2013 (63.5% for young women), the GDP fell by 25%, and the suicide rate rose by 35% between 2010 and 2012 alone. By 2016, more than a third of the Greek population was at risk of poverty or social exclusion.

In the face of extreme austerity and welfare state retrenchment, the strong presence of the ‘Greek family’ has played a pivotal role in preventing the exacerbation of, what some called, a humanitarian catastrophe. Apart from being a source of emotional support, ‘the family’ often replaced the failing welfare state on multiple fronts. Large numbers of women assumed caring roles, looking after the family’s children and elderly members. The transfer of money within the extended family also kept many of its members financially afloat, with one in three indebted Greeks asking for financial help from their parents. Moreover, unable to afford housing, many young adults stayed with their parents for much longer than they normally would, or returned to their parental home after having left for years. Even though the Greeks’ confidence in domestic and international political institutions and actors has declined dramatically in the last decade, the family continued to constitute the most trusted institution.

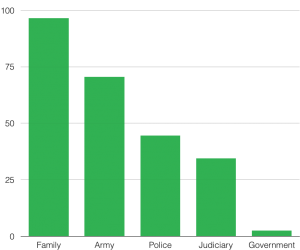

Figure 1: Trust in institutions, 2018

Source: Dianeosis 2018 A, available online at: https://www.dianeosis.org/2018/03/greeks-believe-2018/

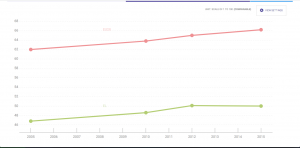

Nonetheless, the role of the family in the context of the crisis, has not been necessarily positive for all family members. The fact that large numbers of women returned to the traditional gender role of ‘housewives’ might have been helpful for the family as a whole, but it compromised—among other things—their own economic independence. It is indicative that the rate of progress towards gender equality was slowed down during the crisis years, opening up further the gap between Greece and the EU average, and placing Greece in the last position among all EU countries.

Figure 2: Gender Equality Index, for the EU and Greece, 2005-2015

Source: EIGE, https://eige.europa.eu/gender-statistics

Although it is rather clear that the crisis caused a return towards more traditional gender roles and dynamics, the connection between the crisis and domestic violence is less clear, as the crisis coincided with a number of co-occurring phenomena:

- The 3500/2006 law for combating domestic violence was implemented only three years prior to the beginning of the economic crisis. Therefore, any changes in recorded incidents may merely reflect that a greater range of behaviours are now officially considered criminal.

- The General Secretariat for Gender Equality has made considerable steps towards providing support to domestic violence victims and raising public awareness. These efforts materialised from 2011 on—soon after the economic crisis began. Once again, a potential upward trend in recorded incidents might only reflect increased levels of awareness and use of services.

- Since 2015, with the so called ‘refugee crisis’, the concept of violence against women has resurfaced in the public debate, often framed in terms of ‘cultural difference’. Here, the increased perception levels are not to be conflated with an increase in actual rates.

Considering the above, and since there is no available data that would (a) capture the true numbers of domestic violence incidents and (b) allow us to compare the ‘before’ and ‘after’ the crisis rates, we cannot confidently argue that the economic crisis has led to an increase in domestic violence.

Nonetheless, our study[1] involving interviews with experts and frontline workers shows that the pedestal on which Greeks place the institution of the family today, hurts the victims of violence more than it helps them. There are three take-away points here:

First, as women lose their economic independence, they also lose their ability to escape romantic relationships that were or became abusive. As a social worker highlights:

It is not their first request to leave, either because they have not thought things through, or because they do not have the economic ability. So, they return to their perpetrator because he was paying for them or because they listen to their family environment …

As this quote suggests, the economic dependence as well as the family influence, may deter victims from seeking alternatives. At times, this dependence may also be the very tool of abuse, meaning one intimate partner controls the other partner’s access to economic resources, thereby controlling their individual freedom.

Second, Greek women still hold dear the ideal of a cohesive nuclear family, which they are willing to preserve at any cost. This includes protecting the family’s reputation, preserving the status of men as the heads of the household, and avoiding the stigma associated with divorce. As an expert lawyer puts it:

Most [victimized] women hold the belief: “he is the man and he got angry”. Or, “But, am I going to divorce? What will my folks say? My folks consider him a good guy”. Or, they come for advice and they tell you, “I’m not ready to break up my household. Are children going to grow up without their dad?” […]. And, there is this so deeply rooted ideal of the family that in order for them not to ruin it […] they go on and choose the living hell.

Third, even when victims come to the difficult decision to report an incident, police officers may also discourage them in the name of the family. As a social worker explains:

There are some incidents in which they [the victims] want to go to file a report, they are ready. And, when they arrive at the police, the police officers, most of them men, discourage them. They rely on their own experiences, or stereotypes, [saying], “come on, go back to your husband”, “come on, forgive him, he will not do it again”, “how is the child going to grow up without a dad?” – so women immediately retreat and go away without reporting.

As it appears, in times of severe economic social disruption, the Greek family has played a dual role, both helping family members cope and holding some of them ‘captive’ in abusive relationships. Our research brings into sharp relief the link between economic and gender inequalities, on which the Greek social model is based. Considering also that the cost of intimate partner violence against women is estimated to be €2.4 billion per year for Greece, it is a call for policy-makers to decouple the protection of the economically vulnerable from familial structures of support. Because, in the path to economic recovery, there is also a need for equitable protection of social and human rights.

More specifically, our research points towards the following policy recommendations:

- With the aim to boost women’s economic independence:

- Expansion of subsidised childcare programmes

- Enforcement of Maternity Leave Policy

- Expansion and enforcement of Paternity Leave Policy

- Introduction of programmes that assist job continuity for women after giving birth

- Expansion of programmes for the care of the elderly

- With the aim to combat domestic violence:

- Introduction of preventative measures:

- Awareness raising—especially among teachers, police officers, and public health professionals

- Campaigns for the elimination of gender stereotypes that normalise violence

- Improvement of the coordination of organisations that work to protect victims of violence on the ground

- Single, shared database of recorded incidents

- Clear channels of communication and cooperation

- Introduction of correctional programmes for domestic violence offenders

- Mental health support

- Mandatory educational & treatment programmes

[1] This study was funded by ActionAid Hellas as a part of the organisation’s mandate in terms of advocacy and policy change in the field of women’ s rights. Read the study here .

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of Greece@LSE, the Hellenic Observatory or the London School of Economics.