The implosion of the sovereign debt crisis in Greece shook the foundations of Greece’s economic relations with its Western Balkan neighbours, essentially reversing years of consistent growth and breaking the momentum of dynamic economic relations that had been constructed over more than a decade. The deterioration of the domestic economic environment had a deep and resonating impact on the Greek economy as well as on practically all dimensions of Greece’s relations with the countries of the region. The perception of Greece’s role was also diminished by ongoing bilateral tensions, especially between Greece and Albania, North Macedonia, and the non-recognition of Kosovo.

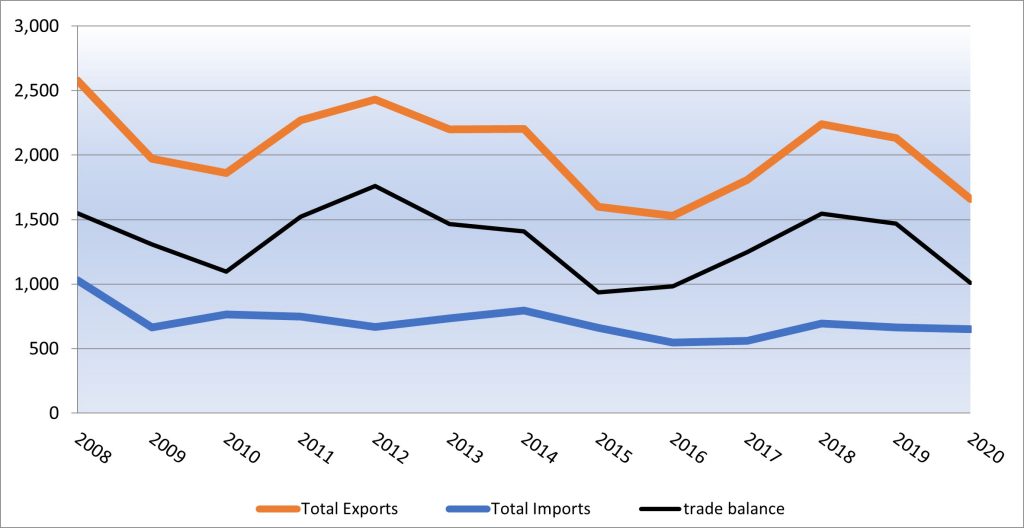

Since 2016, however, one observes a change in direction in both the political and economic fields. Athens prioritized the resolution of all problems with Skopje and Tirana and trade transactions substantially recovered, with exports and the trade surplus almost reaching the pre-crisis levels (before declining again due to the impact of the pandemic) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Greece’s Total Trade with the Western Balkans, 2008-2020 ($US mn)

Source: United Nations Comtrade Database

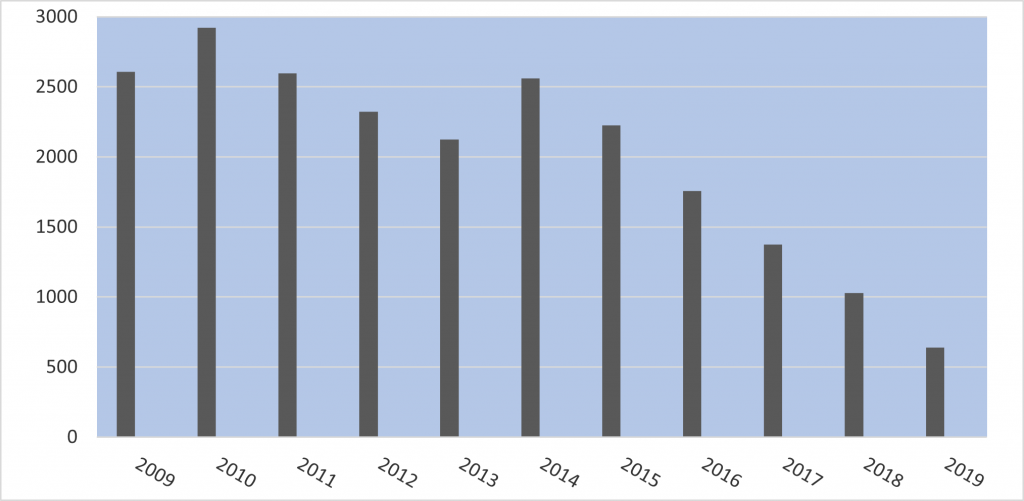

However, the downward trend of Greek investment in the Western Balkans that had started in 2009 has shown no signs of recovering: FDI stocks declined consistently between 2014-2019, falling from €2,559 million to €638 million (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Total Greek FDI in the Western Balkans (stock, €mn)

Source: Bank of Greece

This negative trend was particularly evident in the banking sector, where the collapse of Greek investment culminated in the withdrawal of many Greek banks.

Greek businesses face challenges in their transactions with the region that go beyond the impact of the crisis and are far more complex. In varying degrees, most of the countries Greek businesses interact with exhibit detrimental characteristics that include democratic backsliding, state capture, weak rule of law, corruption, persistence of protectionist practices, cumbersome bureaucratic procedures, and uneven competition in public procurement and imports. Greek businesses have also faced many challenges that are linked to the lack of an efficient state economic diplomacy to support, facilitate, and protect Greek business initiatives in the region.

In 2019 the Greek state launched a process aimed at restructuring and reinvigorating economic diplomacy. Important steps have already been taken, including the transfer of full jurisdiction to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the articulation of a national strategic plan for extroversion with key performance indicators, and a revival of the international development cooperation agency. The policy overhaul is ongoing and key aspects are still incomplete: for instance, new state agencies/divisions – such as the Directorate of Strategic and Operational Planning, and the Council for Extroversion – have just become operational. Similarly, important reforms are still under way, such as restructuring of the Export Credit Insurance Organisation and upgrading the human resources of Enterprise Greece. In this respect, the impact of administrative reforms cannot yet be fully assessed.

Our research showed that most public and private actors that are invested in Greece’s economic involvement in the Western Balkans strive to coordinate their activities. Nevertheless, their cooperation seems to be on an ad hoc basis and is dependent on the field experience and level of commitment of the people who are actively involved from each side. Therefore, Greek economic diplomacy vis à vis the region will be strengthened if certain aspects are reinforced, entrenched, and implemented in a more systematic way. The following paragraphs outline some ideas worth exploring:

1.Networking and coordination

Considering the plurality of actors who get involved in international economic relations, the performance of economic diplomacy heavily depends on continuous networking and coordination.

Regular visits by the leadership of the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs empowers the Greek diplomatic missions in the countries of their operation. These tours should be followed up by contacts between Ministers with different portfolios (e.g., energy, transport, tourism, and culture) from Greece and these countries to advance cooperation in specific fields of activity. There are at least three areas of concern where Greece should enhance its cooperation with its northern neighbours:

- Greece has not concluded agreements for the avoidance of double taxation with North Macedonia, Montenegro, and Kosovo (whose independence it has not recognized).

- Athens should put all administrative and custom-related problems that Greek businesses face in the region on the table more consistently.

- Athens should advocate for the improvement of the region’s antiquated transport infrastructure.

In addition, consultations between public and private actors should be systematic and should take place at different stages of policy making, and across different sectors of economic activity.

- The newly established Council for Extroversion could assume a central role with more responsibilities and a greater spectrum of activities.

- The activities of Greek companies impact not only their corporate brand names but also the image of their countries of origin. The Greek state could consider establishing a distinct Corporate Social Responsibility division (in the Directorate B of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) that could support responsible corporate practices.

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs could organize information activities with the participation of economic counsellors deployed in the Western Balkans and business representatives in Greece.

- Greek companies intending to bid for EU-financed projects in Western Balkan countries should better inform the diplomatic missions in place as there is an informal EU norm of making sure that companies from all interested EU members get a market share.

The advancement of Greek economic diplomacy goals also necessitates that Greek actors reach out to their counterparts from other countries to join forces and increase their efficiency:

- Greek diplomatic officers should always engage EU institutions and other EU member-states when Greek companies face challenges in the Western Balkans relating to the operation of rule of law institutions, or obligations deriving from their Stabilization and Association Agreements.

- Greek corporations should also seek membership in sectoral associations (e.g. associations of banks) in the countries of their operation, as well as in larger Chambers and Associations where other like-minded foreign corporations are also members, such as the American Chambers of Commerce and the Foreign Investors Councils.

2.Increase the efficiency of Greek diplomatic corps

The expansion of Greece’s economic relations with Western Balkan countries requires the production of a greater number of sectoral studies on specific fields of activity per country, to properly inform producers and prospective investors and help them adequately prepare. The Diplomatic Missions in the Western Balkans should be more closely linked with Enterprise Greece. While the former have the advantage of field presence and familiarity with diplomacy, the latter has greater resources and more specialized knowledge of the traits of Greek export-oriented companies.

The output of diplomatic missions varies across time and space and is largely dependent on the performance of people dispatched in these locations. The annual reports of the Offices of Economic and Commercial Affairs could follow a more reader-friendly template that would render them more accessible to a wider non-specialized audience. The guidance of officers should also commence in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs at the very moment of their assignment to a new post. The Ministry may consider developing standard operating procedures to guide diplomatic work abroad. Last, but not least, it should also equip Diplomatic Missions with an adequate budget to carry out a variety of activities.

To conclude, while Greek FDI has been retreating from the Western Balkans over the past few years, the Greek state has been making consistent and important efforts to reinvigorate its economic diplomacy towards the region. However, while significant progress has been achieved, there is still room for the development of further synergies and additional actions by both public and private actors: this would maximize the potential of Greek businesses, improve economic relations, and enhance the country’s overall presence in the region.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of Greece@LSE, the Hellenic Observatory or the London School of Economics.