Introduction

In May 2023, a parliamentary election was held in Greece, at the end of the term of the New Democracy (ND) government, in office since July 2019. The election was the first since 1989 to be held with a proportional representation (PR) electoral system. ND won the election, as expected by the opinion polls. However, the results came as a shock because of the twenty-point difference with major opposition SYRIZA (Table 1), thus resulting to a party system that is heading towards the predominant party category. Expectedly, a new election was held one month later with a new electoral system of majoritarian tendency. ND won again and formed its second consecutive single-party government. Possible determinants of these outcomes include the large approval of ND’s economic performance, combined with a biased media environment and a poor performance by the opposition, mainly SYRIZA.

Table 1: Greece, National elections results, 2019-2023

| 2019 | May 2023 | June 2023 | |

| ND | 39.9 | 40.8 | 40.6 |

| SYRIZA | 31.5 | 20.1 | 17.8 |

| PASOK | 8.1 | 11.5 | 11.8 |

| KKE | 5.3 | 7.2 | 7.7 |

| Spartans | – | – | 4.7 |

| Greek Solution | 3.7 | 4.5 | 4.4 |

| Victory (NIKI) | – | 2.9 | 3.7 |

| Freedom Course | 1.5 | 2.9 | 3.2 |

| MeRA25 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 2.5 |

| Other | 6.6 | 10.1 | 6.1 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Note: Only parties that pass the 3% threshold enter the Parliament.

The designation of a party system as falling into the predominant category is not a mere fetish of political scientists. It has serious implications about the dynamics of a given political system and the quality of democracy itself, since it implies the absence of a potent opposition and the checks and balances it can secure. For instance, it is the first time that the major opposition cannot call for a vote of confidence because of its small number of MPs.

Background to the election

After the outburst of the economic crisis in 2010, Greece had to sign three Memorandums of Understanding (MoUs) with its creditors between 2010-2015, to avoid default. The MoUs, which entailed harsh austerity measures and structural reforms, formed the main divide of the Greek political system, between anti- and pro-MoU forces, which was also an anti-/pro-EU divide, albeit with variations in content and intensity. After a period of four pro-MoU and two anti-MoU governments (which turned pro-MoU), the implosion of the old party system, four national elections, two European elections, and a referendum, in 2019 ND won the election and formed the first single party government since November 2011. This result affirmed a stabilization process and a slow return to bipartisanism.

The major issues that the ND government had to face was an early refugee crisis, the Covid-19 pandemic and the repercussions of the war in Ukraine. In the last year before the May 2023 election, two other issues had the potential to influence the outcome but finally did not:

- a) In August 2022, Prime-minister Mitsotakis admitted that the Greek National Intelligence Agency had been wiretapping the president of PASOK party, Androulakis, insisting that everything was done legally. More names of politicians and journalists were leaked as wiretapping targets in a scandal deemed the Greek ‘Watergate’, for which the Greek judicial system, the European Union and the European Parliament started investigations that were not concluded at the time of the election.

- b) Three months before the election, a tragic train accident happened in central Greece, claiming the lives of 57 people, many of them students, highlighting timeless problems of the public sector, as well as specific responsibilities of the ND government. The accident sparked protests and demonstrations, especially among the young, with the moto ‘Pare otan ftaseis’ (call me when you arrive). Temporarily it seemed that the accident could affect the voting behavior of young people, serving as a politically socializing experience. In the end it did not play a significant role since ND dominated in the 17-24 age cohort for the first time after the outburst of the economic crisis[1].

The problem of media pluralism in Greece

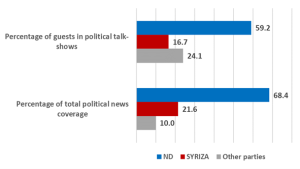

Any analysis pertaining to the Greek political system should refer to the situation regarding pluralism in broadcast media, which seems to be on the wane. The Constitution mandates that the radio and television are ‘directly regulated by the state, aiming at the objective and impartial transmission of information and news’ but there is evidence that this provision is not followed. For instance, the Covid-19 pandemic coincided with the ‘Petsas list’ scandal, where the government provided unequal and disproportional financial support to some media outlets, using funds from the Temporary Framework pertaining to the Covid-19 pandemic (Giosa, 2023). The Greek National Transparency Authority still refuses to this day to investigate the issue. Also, the European Center for Press Media and Freedom (2022) concludes that ‘ […] the country fails to meet any of the relevant recommendations issued by the European Commission’. Moreover, according to the Greek regulator, ND receives the lion share of coverage in political talk shows and news programs, both in terms of guests and time allocated (Graph 1).

Graph 1: Political pluralism, 2021: Average-all 6 TV stations with a nationwide reach in Greece. (5 private, 1 public service).

Source: NCRTV, 2022.

Note: Data are gathered and reported to NCRTV by the TV stations themselves.

Campaign

It is interesting that the Greek electorate defied the proportionality of the electoral system in the May election. ND’s victory was so impressive that they nearly achieved a single-party government through a PR electoral system, gaining 146 out of the 300 parliamentary seats. During the campaign, all parties, except for SYRIZA, had ruled out the possibility of coalition government formation. SYRIZA’s ambiguous and self-undermining tactic was that they would consider their participation in a coalition government only if they won the election, naming any other option as a ‘government of losers.’

Regarding the election campaign itself, ND’s main slogan was ‘Steady, boldly, forward’ and the campaign revolved much around its leader, Prime-Minister Mitsotakis. SYRIZA’s May slogans were ‘Justice Everywhere’ and ‘We have the knowhow and we can bring about change’. In June, they used ‘Well-being for all in a just society’. SYRIZA tried to connect with the glorious PASOK past by using the emblematic word ‘change’ (‘allagi’) but its campaign was rather passive and even obscure at some points. PASOK also used the same symbolical term (‘We make change possible’) and had a rather social-democratic agenda, which targeted specific audiences.

The Greek Communist Party (KKE) underlined the need for social solidarity and class organization against the EU and NATO. The newly formed Spartans, which was endorsed by former neo-nazi members of the once prominent Golden Dawn, had an expected nationalist, racist, anti-immigrant but not anti-EU agenda. Greek Solution, an extreme right populist party, also had a nationalistic, anti-immigrant agenda. Another new extreme right party, Victory, focused on traditional family values, being anti-abortion. Finally, Course of Freedom, the party of a former Speaker of the House, had a rather nationalistic-populist agenda and its campaign was centered around its leader.

Results: The main take-away points.

Turnout increased by 300 thousand voters in May, compared to 2019. In June, turnout was expectedly lower since the June election was rather treated as a ‘second order’ election because the winner was certain. The 2023 elections were also marked by two (almost) unprecedented elements. Firstly, it was the first time after 2000 that the incumbent party’s vote share increased after a full 4-year term. Secondly, the first-second party difference in the June 2023 election was the biggest after 1974.

ND won in 58 out of the 59 electoral districts performing better than 2019 in slightly more than half of them. However, in May it performed worse in 11 out of the 15 Macedonian districts, something that could imply a possible ‘Prespa’ effect, because ND did not fulfill its promise of cancelling the homonymous agreement with North Macedonia, which was a very salient issue in these areas. ND dominated in every sociodemographic category.

SYRIZA won in only one district and performed worse than 2019 everywhere else, more so in its past strongholds. In June it trailed PASOK in 11 districts. It did not win in any sociodemographic category for the first time since its meteoric climb in 2012. It is safe to assert that SYRIZA is not a contender of power anymore.

PASOK increased its vote share in every electoral district, compared to 2019. However, it had a rather poor performance in urban areas, Athens and Thessaloniki, where it lost 8 out of 10 districts to KKE. KKE performed better than 2019 in every district. The Spartans were geographically balanced and had a notable appeal amongst unemployed (9.5%). Greek Solution and Victory performed significantly better in Northern Greece with the former having an older audience comprising mostly men and the latter a more gender balanced electorate. Freedom Course’s vote was balanced in terms of geography and gender, while it performed better amongst those identifying as center-left (6.5%).

Obviously, one of the main features of the 2023 election in Greece is the return of the extreme right, which sums almost 13%. This re-appearance is linked to the normalization of racism and hate speech in the Greek public sphere and, at the same time, poses a threat to ND’s dominance from its right.

Economic voting

Economic voting’s major premise is that macro-economic performance influences electoral behavior. Voters are supposed to punish or reward those who handle the economy (Alesina & Rosenthal, 1995/Lewis-Beck & Paldam, 2000). There can be sociotropic and pocketbook economic voting, and the evaluations can be both retrospective and prospective. There was evidence of economic voting in Greece during the economic crisis (Tsirbas, 2016; Artelaris and Tsirbas, 2021). The economic voting hypothesis’ plausibility in 2023 is based on the economic environment, which was characterized by an unprecedented annual growth of 8.4% after the pandemic (World Bank, n.d.), unemployment of 11.4% in 2023 compared to 17.3% in 2019 (ELSTAT, 2023) and the successful attribution of high inflation to the war in Ukraine. Moreover, many of ND’s measures to tackle the effects of inflation, in the form of direct pocket money, proved quite popular.

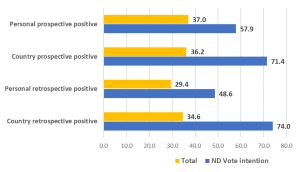

Data from the Voting Advice Application (VAA) What2Vote.gr demonstrate that amongst those who expressed the intention to vote for ND, positive economic evaluations, pocketbook and sociotropic alike, were overwhelmingly higher, both retrospectively and prospectively, providing support for the economic voting argument (Graph 2). Obviously, one should consider the ‘chicken and egg’ problem, which implies that people could make positive evaluations because they wanted to vote for ND. Also, VAAs have the notorious self-selection bias issue. Nevertheless, both the economic environment and the available data point to economic voting as one of the determinants of the 2023 electoral results.

Graph 2: Evidence of economic voting, May 2023 election.

Source: VAA What2Vote

N=14.709

Weighted according to age, gender, administrative district, and vote in the July 2019 election

All crosstabs statistically significant at the 95% level

A predominant party system? Not quite there yet, but…

A predominant party system is one where the same party wins the absolute majority of parliamentary seats or wins the election and is a necessary partner for a coalition government, for at least three consecutive elections (Sartori, 1976). During the 1950’s and 1960’s different versions of the Right’s major party (ND’s direct predecessors) won six consecutive elections in the last occurrence of a predominant party system in Greece.

So, if ND wins the next election, we are officially there. Sartori also stresses that predominant party systems remain competitive and have a degree of fluidity. Indeed, fluidity seems to be on the rise in Greece, as many relevant indicators, like the sum of two first parties’ vote shares, the number of effective parties and vote nationalization scores point towards this direction.

Conclusion

In sum, the 2023 elections had some unprecedented features which marked the moving towards a predominant party system, with ND being the dominant power. Economic voting seems to be a major determinant of the outcomes, in a political environment of waning political pluralism, weak opposition and rising extreme right. These developments could raise some serious concerns about the functioning of democracy in Greece, in the near future.

References

Alesina A. and Rosenthal H. (1995), Partisan politics, divided government and the economy. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Artelaris, P., and Tsirbas, Y. (2018) ‘Anti-austerity voting in an era of economic crisis: Regional evidence from the 2015 referendum in Greece’, Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 36(4): 589-608.

ELSTAT, (16/3/2023), Labor force survey, Athens, Greece. URL: https://www.statistics.gr/el/statistics/-/publication/SJO01/2022-Q4 Accessed 5/10/2023.

European center for Press and Media Freedom-ECPMF, (2022), Controlling the message. Challenges for independent reporting in Greece. Report of the joint fact-finding mission. https://www.ecpmf.eu/controlling-the-message-challenges-for-independent-reporting-in-greece/

Giosa, P., (2023) ‘Assessing the Use of the State Aid Covid Temporary Framework with Regard to the Healthcare and Media Sector’, Journal of European Competition Law & Practice, Volume 14, Issue 5, July 2023, 274–289.

Lewis-Beck, M. S. and Paldam, M. (2000) ‘Economic voting: an introduction’ Electoral Studies, 19, 113-121.

NCRTV, (2022), 2021 Activity Report. Athens, Greece. Available at: https://www.esr.gr/wp-content/uploads/EP2021.pdf Accessed 29 September 2023.

Sartori, G. (1976) Parties and party systems. A framework for analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tsirbas, Y., (2016) ‘The January 2015 Parliamentary Election in Greece: Government Change, Partial Punishment and Hesitant Stabilisation’, South European Society and Politics, 21:4, pp. 407-426.

World Bank, (n.d.a.), GDP Growth (annual %) – Greece. URL: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=GR Accessed 5/10/2023.

[1] Source of all the relevant data henceforth: Metron Analysis, (2023) Exit Poll of the May 2023 election. Results report. Athens: Metron Analysis Polling Agency. URL: https://shorturl.at/aqAS8 Accessed 5/10/2023.

*The Hellenic Observatory hosted a research seminar on the topic on 24 October 2023. For more information please visit the event page.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of Greece@LSE, the Hellenic Observatory or the London School of Economics.