The practice of manual scavenging is a violation of human rights that needs to be addressed in health and sanitation policy reform. Caste-based discrimination and lack of technological innovation is at the root of the issue. Arunbalaji Selvaraj, explores how law enforcement, economic empowerment, increasing awareness and upgrading sanitary infrastructure are essential to upholding human rights.

Manual scavenging, a practice distinct and far more perilous than regular janitorial work, involves the hazardous and inhumane task of manually handling human waste from dry latrines and sewers. Still shockingly prevalent in various regions of India, this practice starkly contrasts with the role of janitors, who typically engage in the cleaning and maintenance of buildings and spaces, using tools and equipment that minimise direct contact with waste. Despite the enactment of the Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act in 2013, aimed at abolishing this degrading practice, significant implementation gaps and societal bias have allowed it to persist. Addressing the plight of manual scavengers transcends legal enforcement; it is a pressing humanitarian issue that demands immediate action to protect human dignity, uphold human rights, and foster profound social reform. The persistence of manual scavenging is not just a failure of policy but a reflection of deep-seated social inequities, emphasising the need for a collective societal effort towards empathy, understanding, and tangible change.

The Humanitarian Crisis of Manual Scavenging

Manual scavenging represents a grotesque violation of basic human rights and dignity. Those involved in manual scavenging are exposed to numerous health risks, including harmful gases and pathogens that can lead to diseases like leptospirosis, hepatitis, and helicobacter. Tragically, many manual scavengers lose their lives each year due to accidents in septic tanks and sewers, incidents that could have been largely preventable with proper safety measures and equipment.

The distressing reality of this situation is further amplified considering the role of manual scavengers in maintaining some of India’s busiest public spaces. In a country with a population exceeding 1.3 billion, the scale of public facilities and their usage is immense. For instance, India’s railway stations, an extensive network that handles over 23 million passengers daily, and bus stands bustling with activity round the clock, often rely on manual scavenging for sanitation maintenance. Furthermore, the toilets on Indian trains, which form arguably the longest toilet line globally, are manually cleaned after their journeys. In 2019 alone, Indian Railways, the world’s fourth-largest rail network, carried over 8 billion passengers. These statistics are not just numbers; they represent the immense scale of public usage and the consequent burden placed on manual scavengers, underlining the urgent need for comprehensive reforms in sanitation management and social attitudes. These figures starkly illustrate the intense demand placed on public sanitation facilities in India and the dire need for sustainable and humane waste management practices. This scenario underscores a deep-rooted societal indifference towards the wellbeing and dignity of manual scavengers, and highlights an urgent need for systemic change.

The Intersection with Caste Discrimination

To address the issue of caste-based discrimination in the context of manual scavenging in India, it’s important to look at the available data. According to government data, an overwhelming 97% of manual scavengers in India are Dalits, highlighting the strong link between caste and this practice. Specifically, about 42,594 manual scavengers belong to Scheduled Castes (SCs), 421 to Scheduled Tribes (STs), and 431 to Other Backward Classes (OBCs). This data starkly illustrates the caste-based nature of manual scavenging and underscores the need to recognise and address this issue as a form of caste-based violence and discrimination.

However, it’s also noteworthy that there is often a lack of comprehensive data or an underreporting of figures related to manual scavenging, partly due to its illegal status and the associated stigma. This absence of detailed national records can be seen as an element of societal indifference towards lower-caste workers, further marginalising them and perpetuating the cycle of discrimination and exclusion.

Therefore, when discussing manual scavenging in the context of caste-based discrimination in India, it is crucial to not only consider the available statistics but also to acknowledge the gaps in data which may reflect a broader issue of societal indifference and neglect towards marginalised communities.

The disparity in technological innovation raises a critical question: why haven’t we seen similar advancements in sanitation technology, especially for manual scavenging? In 2023, the kitchen appliance industry witnessed remarkable innovations such as smart ovens with internal cameras, high-tech microwaves with voice control, and water-saving dishwashers. Yet, there seems to be a glaring absence of similar progress in developing machinery for sanitation purposes. This contrast not only highlights a societal and industrial bias towards convenience over essential public health needs but also reflects a deeper assumption that the manual handling of waste is an unalterable status quo. The lack of progress in this area is not just a technological oversight; it represents a societal indifference towards the plight of manual scavengers and the urgency to innovate in ways that uphold their dignity and safety.

In India, a nation known for its democratic values and cultural diversity, the persistence of manual scavenging in the 21st century is vehemently criticised by numerous campaigners and activists, who label it a ‘national shame.’ This practice not only contravenes the tenets of social, economic, and political justice enshrined in the Indian Constitution but also mirrors a modern form of slavery. A significant reference in this context is a 2014 report by Human Rights Watch, an internationally recognised non-profit organisation. This report highlights the severe implications of manual scavenging and includes a poignant statement from a campaigner: “The manual carrying of human faeces is not a form of employment, but an injustice akin to slavery.” Such powerful advocacy underscores the urgent need for systemic change to eradicate this practice and uphold the dignity and rights of all citizens in India.

The onus of mechanising sanitation work is upon us. But who will take up this responsibility? The government, while the most obvious answer, has numerous other issues to tackle. Despite laws prohibiting manual scavenging, only a handful of cases are ever filed against violators, highlighting a societal indifference to the plight of manual scavengers.

Have you recently used a public toilet? While these facilities are essential for public hygiene, their upkeep often reflects broader social and environmental challenges. Despite varying conditions, these spaces require regular maintenance, a task undertaken by dedicated workers whose efforts are seldom recognised. To truly appreciate the challenges faced by those tasked with cleaning public toilets, one need not perform their job; a mere reflection on their daily experiences offers profound insights into the complexities of manual scavenging. It’s not just about the physical act of cleaning but also about understanding the societal indifference and lack of adequate resources that these workers often encounter. This context brings to light the significant impact of manual scavenging on both individual dignity and broader social dynamics.

Increasing awareness about the plight of manual scavengers can inspire us to act. We all need to lend our voices to the cause of ending manual scavenging and seek ways to eliminate human involvement in this demeaning task. It’s time for a collective societal effort to replace manual scavenging with more dignified, safer, and mechanised methods of sanitation. This issue transcends technological innovation or policy change – it’s about human dignity and social justice. Below are five ways in which the issue can be tackled.

Eradicating manual scavenging: a multifaceted approach

1.Technological intervention: Modern sanitation technologies such as automated sewer cleaning machines and robots can significantly reduce the dependence on human labour for cleaning sewers and septic tanks.

2.Enforcing the law: Enforcement of the law prohibiting manual scavenging remains weak. We need stricter punitive measures, more frequent inspections, and strong political resolve for real change.

3.Rehabilitation and economic empowerment: Comprehensive rehabilitation for manual scavengers is essential, encompassing education, skill development training, financial aid, and access to dignified employment opportunities.

4.Increasing public awareness: Wide-ranging awareness campaigns about the human rights abuses and health risks associated with manual scavenging can foster empathy, build public support for the abolition of the practice, and put pressure on authorities to act.

5.Upgrading sanitation infrastructure: Investments in improved sanitation infrastructure, including sewage and sewage treatment systems, and providing universal access to safe and hygienic toilets, can eliminate the need for manual scavenging.

In a country that has achieved technological milestones like launching rockets into space and inventing machines to automate complex tasks, the lack of technological solutions to eliminate manual scavenging is an irony. Surely, a country capable of exploring distant planets can devise a solution to end this inhuman practice.

The eradication of manual scavenging in India is not merely a task of implementing laws or introducing new technologies; it’s deeply intertwined with addressing the systemic caste and class divisions that perpetuate this practice. It requires strategic investments in impoverished urban and rural areas where this practice is most prevalent. The government and civil society organisations have been working on several fronts to combat this issue. There are ongoing social campaigns within India, such as the Safai Karmachari Andolan, which advocate for the rights and rehabilitation of manual scavengers. The government, on its part, has enacted legislation like the Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act, 2013, and has initiated various projects and innovative solutions, such as the introduction of mechanised sewer cleaning systems, to phase out manual scavenging. However, the challenge lies in effective implementation and ensuring these measures reach the grassroots level.

It’s imperative to understand that manual scavenging is both an urban and rural issue in India, affecting the marginalised sections of society. Therefore, the approach to eradicating manual scavenging must be holistic, encompassing legal enforcement, economic empowerment, technological solutions, and, most importantly, societal change to dismantle caste-based discrimination. As India progresses toward becoming a modern nation, the elimination of manual scavenging becomes a critical step in this journey, embodying the ethos of social justice and equality. The true measure of a nation’s progress lies in how it treats its most vulnerable citizens. It is time for India to rise to this challenge and ensure a life of dignity and respect for all its people. India’s journey towards modernity and progress will be judged by its ability to eradicate this inhumane practice and uplift its most marginalised communities.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE Human Rights, the Department of Sociology, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

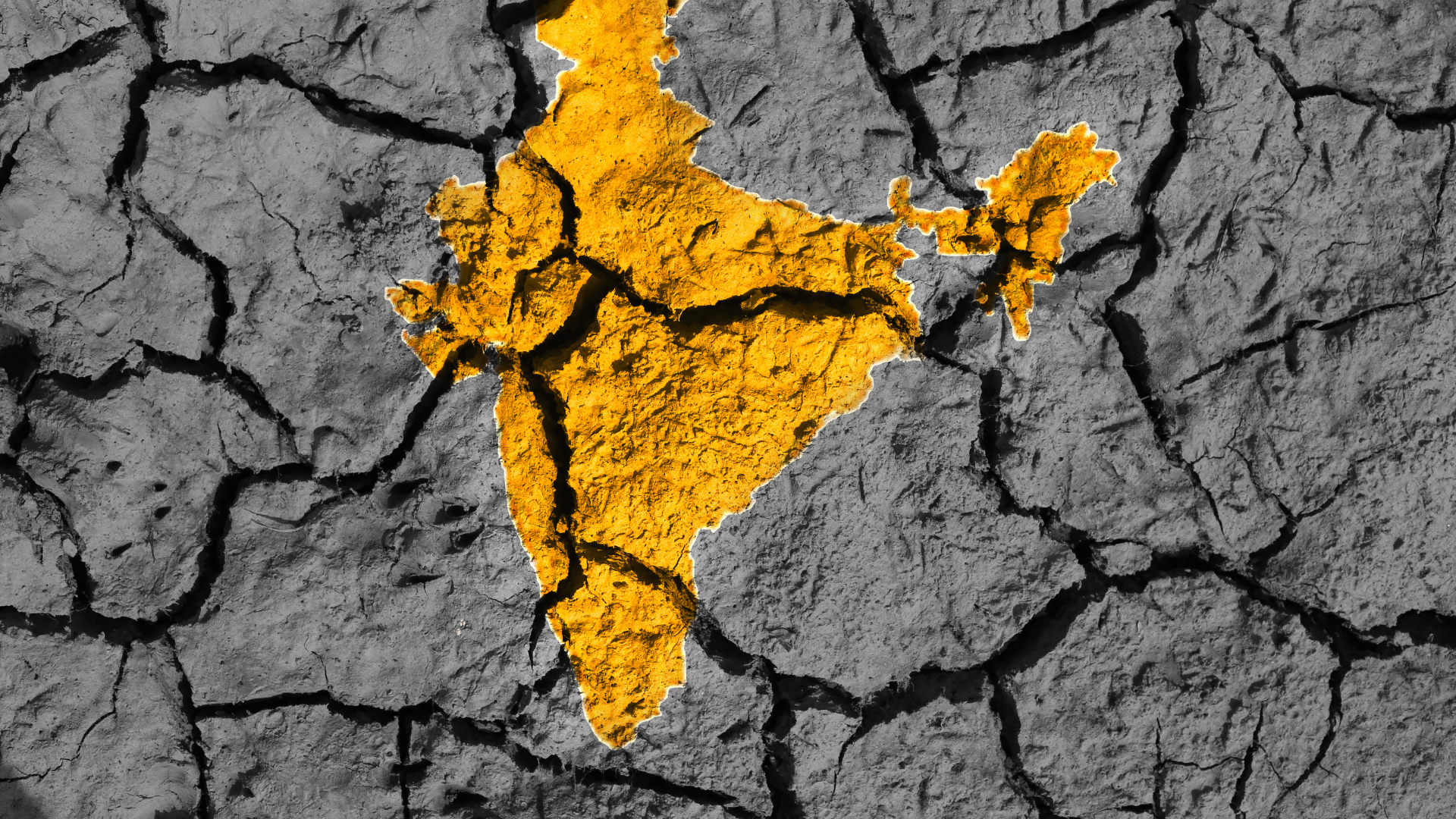

Image credit: Wandering Indian

I sincerely commend the LSE and the author of this article for addressing such inhumane practices in today’s modern era. Your courage to publish and discuss these issues is admirable. In India, there’s often a lack of attention given to such discussions and finding solutions. Keep speaking out and being a voice for the voiceless.

Excellent article. Eventhough rules are there, need to be implemented. At the same time, these people should be provided with alternate employment.

Recently, we came across a news article about a septic tank cleaner who died while cleaning it. Such news often appears in the Indian news media. The author of this article has stated the truth, and it seems no one is paying enough attention to this issue. Only a few activists are discussing it in the media and protesting. Despite Indians dominating global technology and thousands of engineers, techies, doctors, scientists, and researchers from India serving worldwide, this issue remains unaddressed in India. As the article points out, we have the money and expertise to launch rockets in search of water on the moon or Mars, but we fail to manage our own waste, specifically human feces. This is an important topic that needs discussion and resolution. Thank you to the author and the LSE Human Rights Department for highlighting this.

It’s impressive how well you express the issue in writing. You write in a clear and concise manner. I enjoy reading to everything that you have to said.

India’s waste management lags behind despite technological prowess 🌍🚮