The traditional peer-review process is not a 100% reliable filter, argues journal editor Rolf Zwaan. It is foolish to view the published result as the only thing that counts simply because it was published. Replication and community-based review are two tools at our disposal for continuously checking the structural integrity of research. Further mechanisms that support tracking the valuable pre- and post-submission discussion are needed to strengthen the publishing process.

There has been much discussion recently about the role of pre-publication posting and post-publication review. Do they have any roles to play in scientific communication and, if so, what roles precisely? Let’s start with pre-publication posting. It is becoming more and more common for researchers to post papers online before they are published. There even are repositories for this. Some researchers post unpublished experiments on their own website. To be sure, like everything, pre-review posting has its downside, as Brian Nosek recently found out when he encountered one of his own unpublished experiments—that he had posted on his own website—in a questionable open access journal not with himself but with four Pakistani researchers as authors. But the pros may outweigh the cons.

In my latest two posts I described a replication attempt we performed of a study by Vohs and Schooler (2008). Tania Lombrozo commented on my posts, calling them an example of pre- publication science gone wild: Zwaan’s blog-reported findings might leave people wondering what to believe, especially if they don’t appreciate the expert scrutiny that unpublished studies have yet to undergo. (It is too ironic not to mention that Lombrozo had declined to peer review a manuscript for the journal I am editing the week before her post.)

The questions Lombrozo poses in her post are legitimate ones. Is it appropriate to publish pre-review findings and how should these be weighed against published findings? There are two responses.

First, it is totally legitimate to report findings pre-publication. We do this all the time at conferences and colloquia. Pre-review posting is useful for the researcher because it is a fast way of receiving feedback that may strengthen the eventual submission to a journal and may lead to the correction of some errors. Of course, not every comment on a blog post is helpful but many are.

The second response is a question. Can we trust peer-reviewed findings? Are the original studies reported fully and correctly? Lombrozo seems to think so. She is wrong.

Let’s take the article by Vohs and Schooler as an example. For one, as I note in my post, the review process did not uncover, as I did in my replication attempt, that the first experiment in that paper used practicing Mormons as subjects. The article simply reports that the subjects were psychology undergraduates. This is potentially problematic because practicing Mormons are not your typical undergraduates and may have specific ideas about free will (see my previous post). The original article also did not report a lot of other things that I mention in my post (and do report about our own experiment).

But there is more, as I found out recently. The article also contains errors in the reporting of Experiment 2. Because the study was published in the 2008 volume of Psychological Science, it is part of the reproducibility project in which various researchers are performing replication attempts of findings published in the 2008 volumes of three journals, which include Psychological Science. The report about the replication attempt of the Vohs and Schooler study is currently being written but some results are already online. We learn for example that the original effect was not replicated, just as in our own study. But my attention was drawn by the following note (in cell BE46): The original author informed me that Study 2 had been analyzed incorrectly in the printed article, which had been corrected by a reader. The corrected analysis made the effect size smaller than stated…

Clearly, the reviewers for the journal must have missed this error; it was detected post-publication by “a reader.” The note says the error was corrected, but there is no record of this that I am aware of. Researchers trying to replicate study 2 from Vohs and Schooler are likely to base their power analyses on the wrong information, thinking that they need fewer subjects that they would actually be needing to have sufficient power.

This is just one example that the review process is not a 100% reliable filter. I am the first one to be thankful for all the hard work that reviewers put in—I rely on hundreds of them each year to make editorial decisions—but I do not think they can be expected to catch all errors in a manuscript.

So if we ask how pre-review findings should be evaluated relative to peer-reviewed findings, the answer is not so clear-cut. Peer-review evidently is no safeguard against crucial errors.

Here is another example, which is also discussed in a recent blogpost by Sanjay Srivastava. A recent article in PLoS ONE titled Does Science make you Moral? reported that priming with concepts related to science prompted more imagined and actual moral behavior. This (self-congratulatory) conclusion was based on four experiments. Because I am genuinely puzzled by the large effects in social priming studies (they use between-subjects designs and relatively few subjects per condition), I tend to read such papers with a specific focus, just like Srivastava did. When I computed the effect size for Study 2 (which was not reported), it turned out to be beyond any belief (even for this type of study). I then noticed that the effect size did not correspond to the F and p values reported in the paper.

I was about to write a comment only to notice that someone had already done so: Sanjay Srivastava. He had noticed the same problem I did as well as several others. The paper’s first author responded to the comment explaining that she had confused standard errors with standard deviations. The standard deviations reported in the paper were actually standard errors. Moreover, on her personal website she wrote that she had discovered she had made the same mistake in two other papers that were published in Psychological Science and the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.

There are three observations to make here. (1) The correction by Sanjay Srivastava is a model of politeness in post-publication review. (2) It is a good thing that PLoS ONE allows for rapid corrections. (3) There should be some way to have the correction feature prominently in the original paper rather than in a sidebar. If not, the error and not the correct information will be propagated through the literature.

Back to the question of what should be believed: the peer-reviewed results or the pre-peer reviewed ones? As the two cases I just described demonstrate, we cannot fully trust the peer-reviewed results; Sanjay Srivastava makes very much the same point. A recent critical review of peer reviews can be found here.

It is foolish to view the published result as the only thing that counts simply because it was published. Science is not like soccer. In soccer a match result stands even if it is the product of a blatantly wrong referee call (e.g., a decision not to award a goal even though the ball was completely past the goal line). Science doesn’t work this way. We need to have a solid foundation of our scientific knowledge. We simply cannot say that once a paper is “in” the results ought to be believed. Post-publication review is important as is illustrated by the discussion in this blog.

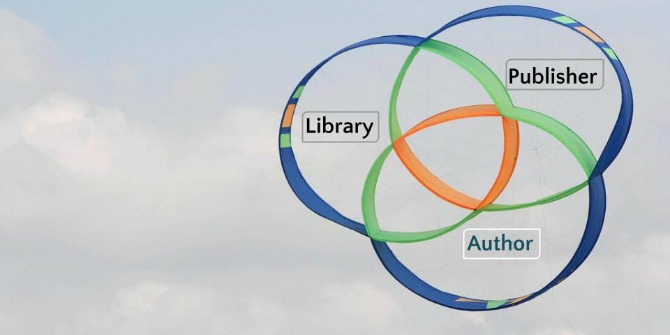

Can we dispense with traditional peer-review in the future? I think we might. We are probably in a transitional phase right now. Community-based evaluation is where we are heading.

This leaves open the question of what to make of the published results that currently exist in the literature. Because community-based evaluation is essentially open-ended—unlike traditional peer review—the foundation upon which we build our science may be solid in some places but weak—or weakening—in other places. Replication and community-based review are two tools at our disposal for continuously checking the structural integrity of our foundation. But this also means the numbers will keep changing.

What we need now is some reliable way to continuously gauge and keep a citable record of the current state of research findings as they are going through the mills of community review and replication. Giving prominence to findings as they were originally reported and published is clearly a mistake.

This article was originally published on Rolf Zwaan’s personal blog and is reposted with permission.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Impact of Social Science blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Rolf Zwaan is Professor of Psychology at Erasmus University, Rotterdam, the Netherlands. He is Editor-in-Chief of Acta Psychologica. His research focuses on language comprehension and mental representation.

Rolf blogs at http://rolfzwaan.blogspot.nl and is on Twitter @RolfZwaan

1 Comments