UK open access policy does not exist in a vacuum. Casey Brienza argues that UK researchers represent too small a proportion of global scholarly knowledge production and consumption to rebalance scholarly expenditure. UK open access initiatives as currently formulated will instead lead to a significant de facto increase in costs for the UK. Instead of paying twice, once to fund the research and again to pay subscription fees to access that research, the public will find itself, in effect, paying thrice—once to fund the research, once to fund open access global publication and dissemination of the results of the research, and a third and final time to pay subscription fees to access critical research conducted throughout the rest of the world.

UK open access policy does not exist in a vacuum. Casey Brienza argues that UK researchers represent too small a proportion of global scholarly knowledge production and consumption to rebalance scholarly expenditure. UK open access initiatives as currently formulated will instead lead to a significant de facto increase in costs for the UK. Instead of paying twice, once to fund the research and again to pay subscription fees to access that research, the public will find itself, in effect, paying thrice—once to fund the research, once to fund open access global publication and dissemination of the results of the research, and a third and final time to pay subscription fees to access critical research conducted throughout the rest of the world.

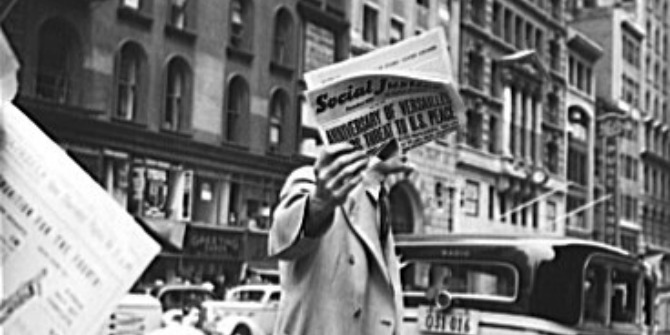

In an April 2013 op-ed for The Guardian, David Willetts, Minister of State for Universities and Science, argued that publicly-funded research findings should not be published “behind paywalls that individuals and small companies cannot afford, even though they have paid for the research through their taxes.” In other words, research which might conceivably fuel entrepreneurial innovation and economic growth beyond the academy is instead being locked away, where few even know it exists, let alone have the resources necessary to access it wholesale. The public, in essence, is being made to pay twice for the fruits of its investment—to the detriment of the greater good.

The traditional subscription model for the publication and dissemination of cutting edge research is, in Willetts’ view, neither morally or financially sustainable, and he proposes open access publishing models as better alternatives. “Open access,” often abbreviated “OA,” refers the unrestricted online availability of peer-reviewed academic research. Specifically, he advocates the so-called “gold open access” model, whereby the costs of publication are paid upfront and the research is made publicly available online immediately, with no embargo period. Gold open access has the advantage of preserving the “quality or reputation of our world-class research base” while protecting “our world-class publishing industry.”

But if UK research councils are to fund research and article processing fees, how is this not still making the public pay twice? In his op-ed, Willetts has a simple answer: “[The cost of gold open access] will be partly met by the research councils and also institutions, which should gradually see their library costs reduce in return.” So instead of paying for journal subscriptions which make research accessible mainly to their staff and students only, universities will pay to make the research they have supported publicly accessible to everybody, and if everybody in Britain does the same thing at the same time, the need for anybody to pay for journal subscriptions will decrease. Sounds entirely reasonable, right? Right?

Yet Alicia Wise, Elsevier’s Director for Universal Access, speaking before the Business, Innovation, and Skills Committee of the UK House of Commons in April 2013, hedges on precisely this issue when asked whether or not the total cost to universities for published research will go up or down. Her reply is as follows: “No, the total cost of the system does not change depending on whether you have the point of payment on the author’s side or the reader’s side. The total costs of the system are the same but, as you see the majority of content published through open-access fees, you would see a counter-balancing decrease in subscription prices.”

Parliament is presumably concerned about costs to universities within the UK, but even a cursory glance at Elsevier’s website would suggest that the company regards “the system,” to use Wise’s terminology, as being not within the UK but rather worldwide. Indeed, in its 2012 Annual Report, Reed Elsevier reports that the UK represents only 7% of its total revenue across all segments. (North America, by way of comparison, is 52%.) Indeed, in a report commissioned by the Department of Business, Innovation and Skills, Elsevier estimates that the UK’s 4.1% share of the world’s researchers produces 6.4% of the world’s research articles. These numbers are not insignificant, but neither are they particularly large.

The bleak fact of the matter is that researchers in the United Kingdom, while consistently “punching above their weight,” to use the local argot, in global league tables of citations and publications represent too small a proportion of global scholarly knowledge production and consumption to rebalance expenditure throughout “the system” in the way that Willetts suggests in The Guardian op-ed. The single largest producer and consumer of English-language scholarship, the United States, has a system of higher education so organizationally and economically fragmented that a single open access publishing regime would be virtually impossible to implement either top-down or bottom-up there. In other words, UK open access initiatives as currently formulated will undoubtedly lead to a significant de facto increase in costs for the UK. Instead of paying twice, once to fund the research and again to pay subscription fees to access that research, the public will find itself, in effect, paying thrice—once to fund the research, once to fund open access global publication and dissemination of the results of the research, and a third and final time to pay subscription fees to access critical research conducted throughout the rest of the world which does not operate under the same funding regime.

However much UK policymakers might like to believe that they live in on an island metaphorically as well as literally, “the system” is a global one, and any failure to fully account for this basic fact when rethinking academic publishing models is bound to be a costly mistake. Wise and her employer know all too well already that the UK is unlikely to realize significant savings through gold open access, but because open access is being presented to the public as a moral right, with its absence an abject moral failure, the last thing she wants to do is throw cold water on the government’s empty political posturing. Of course she wouldn’t dare tell them that costs to local institutions are likely to continue increasing regardless.

It is therefore high time, I would contend, to stop the posturing and the moralizing about open access and to start taking seriously whether or not its practical implementation does whatever it was intended to do in the first place. If North America is Elsevier’s biggest market for research publications, might it not be argued that paying to make Britain’s research results open access is actually a gigantic taxpayer-funded handout to the United States and Canada? Probably not quite what Willetts had in mind. Yet open access initiatives have tended to be national in the scope of their ambition. How do we even begin to think globally about workable academic publishing models? Well, consulting with academic publishers who already do just that would be a good start. So would taking what they know seriously, even when we don’t like the answers.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Impact of Social Science blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Dr Casey Brienza is a sociologist specializing in the study of the culture industries and transnational cultural production. Over the past several years, her research has progressed along two parallel streams. The first of these is an investigation of the social organization and transnational influence of the culture industries, using manga publishing in the United States as a case study. The second stream is related to the digital technologies of publishing and reading which have emerged at the beginning of the 21st century. She joined City University London as Lecturer in Publishing and Digital Media in March 2013. Casey may be reached through her website or @CaseyBrienza.

Harnad, Stevan (2012) Why the UK Should Not Heed the Finch Report. LSE Impact of Social Sciences Blog, Summer Issue

Harnad, S (2012) Hybrid gold open access and the Chesire cat’s grin: How to repair the new open access policy of RCUK. LSE Impact of Social Sciences Blog September Issue