Questions have been raised over whether allowing comments on blogs and other sites is conducive to wider understanding of science. Jonathan Mendel and Hauke Riesch present a look at how online comments, even uncivil ones, can positively benefit community cohesion and inclusive engagement. But efforts must be taken to challenge destructive behaviour like trolling and to support those targeted with abuse.

Questions have been raised over whether allowing comments on blogs and other sites is conducive to wider understanding of science. Jonathan Mendel and Hauke Riesch present a look at how online comments, even uncivil ones, can positively benefit community cohesion and inclusive engagement. But efforts must be taken to challenge destructive behaviour like trolling and to support those targeted with abuse.

Blogging about science (and academic research in general) has become a prominent tool for researchers to communicate with each other and a wider public, as the LSE Impact blog itself demonstrates. There are several reasons for the high hopes surrounding blogging about science – for example the quick turnaround time, editorial control by the author and perceived ease of public access. However, blogging also comes with risks, challenges and limitations. In Riesch and Mendel (2014) we engaged with these issues by discussing some of the achievements of and challenges faced by the ‘bad science’ blogging network (an informal group of bloggers who gathered around Ben Goldacre’s “Bad Science” forum, starting around 2006). In Mendel and Riesch (forthcoming) we focus on the importance of comment spaces and below-the-line discussions to science blogging. We will draw on this work to discuss some of the potential achievements of – and challenges facing – science blogging and will consider the positive potential of online comments, including uncivil comments.

‘Bad science’ blogging

The ‘bad science’ blogging community sprung from discussions in comment spaces on Goldacre’s ‘bad science’ blog, but also drew on below-the-line discussions more broadly. In the absence of peer reviewers or editorial gatekeepers – and given that some members of the community blog anonymously or don’t have institutional or educational credentials to rely on for their credibility, or both – strategies for building and maintaining credibility become important. Our study of this community has revealed a networked process of credibility construction where the individual blogger relies on the informal peer-review of other bloggers to show that the science they write about is sound, and visibly so.

Interaction between these bloggers and other commentators occurs mainly below the line in the comment space of the blogposts and in other web 2.0 spaces, such as Twitter or the ‘bad science’ community forum. Bloggers rely on these spaces for various types of support and these interactions help in the construction of credibility. Comment spaces also act as a major window of interaction with the world outside the community (and this network has also been involved in some interesting campaigns, ranging from a successful campaign to reform libel laws to attempts to get the Green Party of England and Wales to move away from ‘anti-science’ policies). This community has thus both sprung from comment spaces and depends on these spaces in important ways.

Uncivil Comments: “ARE YOU A CHICKEN-FLAVOURED NIPPLE BISCUIT”

In part because of the outwards-facing, combative nature of this community – it explicitly aims to challenge ‘bad science’ – members regularly face comments disagreeing with them. Some comments are impeccably polite, while others are abusive or threatening. Because of the large role of comment spaces in this community, it is important to consider the impact of uncivil comments.

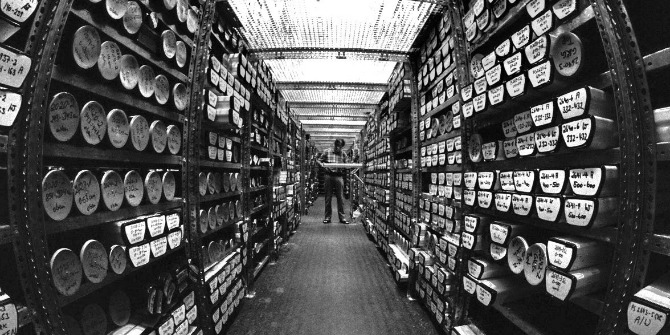

Image credit: Chiltepinster (Wikimedia, CC BY-SA)

Image credit: Chiltepinster (Wikimedia, CC BY-SA)

Anderson et al. (2013) draw on trial-based research to argue that while “[o]nline communication and discussion of new topics such as emerging technologies has [sic] the potential to enrich public deliberation…online incivility may impede this democratic goal.” Their research – and concerns springing from it – has been widely discussed in diverse fora from the Guardian (Bell 2013) to Science (Brossard and Scheufele 2013). Questions have been raised about whether ‘web 2.0’ spaces and places can harm science communication, about whether allowing comments on science communication blogs and other sites is conducive to what is perceived as good understanding and this research has been cited in Popular Science’s explanation of why they closed online comments. However, drawing on our qualitative study of a community springing up from comment spaces, we would point to the positive effects that uncivil comments can have on the community and highlight what might be lost if discussion is closed down.

We should first acknowledge how destructive online abuse can be. Laurie Penny (2011) sums this up vividly when she describes how:

You come to expect it, as a woman writer, particularly if you’re political. You come to expect the vitriol, the insults, the death threats. After a while, the emails and tweets and comments containing graphic fantasies of how and where and with what kitchen implements certain pseudonymous people would like to rape you cease to be shocking

We would clearly not argue that such abuse is a positive way to engage online. It is important to acknowledge the harm that abuse can cause, and we also recognise that – as relatively privileged white men – we are likely to avoid the worst of it ourselves. However, there is a real need for a nuanced discussion of online comment spaces: it is important to recognise the value and potential positive impact of such spaces, as well as their risks. As well as acknowledging harm, we should consider the potential contribution of incivility. We’re not intending to condone the very threatening and/or abusive behaviour that is too often seen online or arguing that abusive comments are a good way to engage, but we would argue that the broad spectrum of behaviour that is put under the label of ‘troll’ can have a range of impacts and may merit quite different responses.

One example we look at is where a commenter on one ‘bad science’ blog – posting under the name “yo momma sucks eggs out leemer bung holes” – asked “ARE YOU A CHICKEN-FLAVOURED NIPPLE BISCUIT”. This was a clearly uncivil ‘trolling’ comment that added nothing of substance to the discussion in the blog-post (which was not about chickens, nipples or biscuits) but which was intended to be insulting. However, looking at the impact of this comment over time and across repeated interactions, the wider community reaction was one of amusement. The phrase “chicken-flavoured nipple biscuit” entered community folklore, becoming a frequently-used in-joke. As such, it made a significant contribution to the shared lived history that defines communities and helps build cohesive identities. In this case, it also helped to build friendships, the informal peer-review networks mentioned above and a support network for when more troubling threats appear (which, in a community based on confronting “bad” science, did happen (see Riesch and Mendel 2014))

Conclusions

Our case study has shown that a network of bloggers springing from below-the-line has amassed achievements ranging from building a community and a type of networked construction of credibility to participation in significant political campaigns. It also reminds us of the importance of considering the impact of uncivil comments and ‘trolling’ over longer-term and repeated interactions, rather than focussing just on immediate responses in situations such as trials: such comments might have unexpectedly positive longer-term effects in areas such as community cohesion.

Kathy Sierra recently returned to blogging about the very real violence of online abuse. Sierra (2014) argues for a move to make online spaces safer, calling for “more options for online spaces, and I hope one of those spaces allows the kind of public conversations and learning we had on Twitter but where women — or anyone — does not feel an undercurrent of fear watching her follower count increase.” Sierra argues that “the worst possible approach would be more aggressive banning, or restricting speech (especially not that), or restricting anonymity”, and we would agree with her opposition to restricting speech and restricting anonymity. Sierra ends with the simple injunction “be nice”. It may be in finding ways of being nice – providing welcoming comment spaces, supporting those targeted with abuse, and challenging ‘trolls’ while also pushing them to find better ways to engage – that we could respond effectively to uncivil comments while also keeping open lively places for discussion.

The full research the post is based on will be coming out as a chapter in the following book: J. Cupples, C. Lukinbeal and S. Mains (Eds.) Mediated Geographies/Geographies of Media (Netherlands: Springer).

References

Anderson, A.A., Brossard, D., Scheufele, D.A., Xenos, M.A, & Ladwig, P. (2013). The “Nasty Effect:” Online Incivility and Risk Perceptions of Emerging Technologies. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. doi: 10.1111/jcc4.12009.

Bell, A. (2013, January 16). Do online comments hurt – or aid – our understanding of science? The Guardian. http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2013/jan/16/online-comments-hurt-aid-understanding-science?CMP=twt_fd

Brossard, D., & Scheufele, D. A. (2013). Science, New Media and the Public. Science, 339(5115), 40-41.

Penny, L. (2011, November 4). A woman’s opinion is the mini-skirt of the internet, Independent. Accessible at http://www.independent.co.uk/voices/commentators/laurie-penny-a-womans-opinion-is-the-miniskirt-of-the-internet-6256946.html

Riesch, H. & Mendel, J. (2014). Science Blogging: Networks, Boundaries and Limitations. Science as Culture, 23(1), 51-72.

Mendel, J. and H. Riesch (forthcoming) “Science blogging below-the-line: a progressive sense of place?” in J. Cupples, C. Lukinbeal and S. Mains (Eds.) Mediated Geographies/Geographies of Media (Netherlands: Springer).

Sierra, K. 2014, October 7). Trouble at the Koolaid Point. Serious Pony. Accessible at http://seriouspony.com/trouble-at-the-koolaid-point/

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Impact of Social Science blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Jonathan Mendel is Lecturer in Human Geography in the School of the Environment at Dundee University. His current work looks at online networks, human trafficking, policing and policy.

Hauke Riesch is Lecturer in Sociology and Communications at Brunel University.

Social justice types, progressives, and many academics are asserting that disagreeing with them on line is equivalent to trolling. How do I know this? It happens to me often. Politically, I am sympathetic to these groups but, with the current climate of extremism and intolerance all along the political spectrum, asking questions or challenging certain points gets you ostracized and villified. This is what is happening online . . . a growing illiberalism regarding freedom of speech and freedom of conscience being justified by specious claims of harassment.

SKYWRITING: A MULTI-EDGED SWORD

I think I might know a bit about the open commentary business, since I’ve been umpiring it since before the Internet (1978-2002). Can’t review it all here, but here are a few observations that revolve around the issues of answerability, mediation, anonymity, filtration, trolling, Whistle-Blowing and Gaussian Roulette.

ANSWERABILITY. People tend to be much more civil and comments tend to be much more substantive if their authors are answerable for them in some way — either with their real names and reputations, or to a moderator or editor who knows their real names or who at least vets comments to exclude the rude, violent or irrelavant ones.

FILTRATION: It may help the reader (and motivate the commentator) if the commentaries are hierarchically classified: Vetted/Non-Anonymous, then Vetted/Anonymous, then Unvetted.

GAUSSIAN ROULETTE: Facilitating legitimate whistle-blowing is an invaluable feature of anonymous commentary, but by the same token, it facilitates trolling, public defamation of named people by anonymous people, and worse.

All in all, skywriting is a nuclear weapon: It can do a lot of good, but it can also do a lot of harm.

Harnad, S. (1978) Inaugural Editorial. Behavioral and Brain Sciences.

http://www.ecs.soton.ac.uk/~harnad/Temp/Kata/bbs.editorial.html

________ (1979) Creative disagreement. The Sciences 19: 18 – 20. http://eprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/3387/

________ (1987) Skywriting (unpublished) Since published as Sky-Writing, Or, When Man First Met Troll. The Atlantic, Spring Issue 2011 http://users.ecs.soton.ac.uk/harnad/skywriting.html

________ (1990) Scholarly Skywriting and the Prepublication Continuum of Scientific Inquiry Psychological Science 1: 342 – 343 http://cogprints.org/1581/

________ (1991) Post-Gutenberg Galaxy: The Fourth Revolution in the Means of Production of Knowledge. Public-Access Computer Systems Review 2 (1): 39 – 53 http://cogprints.org/1580/

________ (1995) Interactive Cognition: Exploring the Potential of Electronic Quote/Commenting. In: B. Gorayska & J.L. Mey (Eds.) Cognitive Technology: In Search of a Humane Interface. Elsevier. Pp. 397-414. http://cogprints.org/1599/

________ (1995) Universal FTP Archives for Esoteric Science and Scholarship: A Subversive Proposal. In: Ann Okerson & James O’Donnell (Eds.) Scholarly Journals at the Crossroads; A Subversive Proposal for Electronic Publishing. Washington, DC., Association of Research Libraries, June 1995. http://www.arl.org/scomm/subversive/toc.html

________ (1997) Learned Inquiry and the Net: The Role of Peer Review, Peer Commentary and Copyright. Learned Publishing 11(4) 283-292. http://cogprints.org/1694/

________ (1998) The invisible hand of peer review. Nature [online] (5 Nov. 1998), Exploit Interactive 5 (2000) http://www.nature.com/nature/webmatters/invisible/invisible.html

________ (2003) Back to the Oral Tradition Through Skywriting at the Speed of Thought. Interdisciplines. http://eprints.ecs.soton.ac.uk/7723/

________ (2002) Valedictory Editorial. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. http://users.ecs.soton.ac.uk/harnad/Temp/bbs.valedict.html

Thanks – very interesting. Some of those in this community have developed a reputation attaching to their pseudonymous identity – also a form of answerability, perhaps.

a growing illiberalism regarding freedom of speech and freedom of conscience being justified by specious claims of harassment.It can do a lot of good, but it can also do a lot of harm.Behavioral and Brain Sciences.http://www.larsjaeger.ch/

The questions with reference to allowing people comment on the blog posts are very much relevant. One thing is for sure, not allowing people to comment would prove it as one-way communication. Bloggers specially the one who are scientists or passionate for science loved to read about comments from those who are passionate for science again. Not allowing people to comment would stop this process of science lovers to indulge in an interesting topic of science. Moreover, comments and feed backs add to the flavor of the blog. It makes it much more interesting. In my opinion, blog comments can be filtered but not disallowed!