Digital publishing in the humanities is set to be discussed at this year’s American Historical Association Annual Meeting. Ahead of the event, Cecy Marden explores how open access outlets provide more than just wider access, but can provide new avenues for this scholarship to be taken. From long-form journalism to Pinterest boards, freely available research is just the starting point.

Digital publishing in the humanities is set to be discussed at this year’s American Historical Association Annual Meeting. Ahead of the event, Cecy Marden explores how open access outlets provide more than just wider access, but can provide new avenues for this scholarship to be taken. From long-form journalism to Pinterest boards, freely available research is just the starting point.

There are so many opportunities and—if we’re honest—challenges for innovation in digital publishing it’s hard to pick one and stick with it, but that’s exactly what I’m going to do because some things are worth sticking with. Open access is the best facilitator of, and the biggest opportunity for, innovation in digital publishing. Publishing research open access means anyone in the world with an Internet connection can read it, instead of just the comparatively infinitesimal group of people who have access to a reasonably wealthy university library. Opportunities don’t get much bigger than that.

Much of the research the Wellcome Trust funds is in the biomedical sciences, but we also support research in the medical humanities. This is frequently published in monographs, and monographs now commonly have print runs in the low to mid hundreds. You won’t find these books in the public library or your local bookshop. You might find them in your university’s library if you’re lucky enough to have access. You will probably find them online but you might balk at the price. This lack of access is a problem!

We believe the research we fund is outstanding, and think everyone should be able to access it (and build upon it). Accordingly, we recently extended our open-access policy to include monographs (and book chapters). The first monographs covered by this policy are only just being published open access, but initial usage data gives some indication of the opportunities open access affords. For example, Fungal Disease in Britain and the United States 1850-2000 by Aya Homei and Michael Worboys was published open access with Palgrave Macmillan in November 2013, and made freely available through PMC Bookshelf and OAPEN (as well as the publisher site and e-retailers like Amazon). So far, the free ePub version has been downloaded from Amazon 300 times. Another 600 PDF copies have been downloaded drom the publisher and repository sites, and nearly 3,000 individuals have accessed the HTML chapters. The true readership across digital platforms may be much greater yet, as the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY) means readers and other content providers and aggregators can share the work. Readers who prefer the printed page have also purchased hard and paperback copies from Palgrave.

We believe the research we fund is outstanding, and think everyone should be able to access it (and build upon it). Accordingly, we recently extended our open-access policy to include monographs (and book chapters). The first monographs covered by this policy are only just being published open access, but initial usage data gives some indication of the opportunities open access affords. For example, Fungal Disease in Britain and the United States 1850-2000 by Aya Homei and Michael Worboys was published open access with Palgrave Macmillan in November 2013, and made freely available through PMC Bookshelf and OAPEN (as well as the publisher site and e-retailers like Amazon). So far, the free ePub version has been downloaded from Amazon 300 times. Another 600 PDF copies have been downloaded drom the publisher and repository sites, and nearly 3,000 individuals have accessed the HTML chapters. The true readership across digital platforms may be much greater yet, as the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC BY) means readers and other content providers and aggregators can share the work. Readers who prefer the printed page have also purchased hard and paperback copies from Palgrave.

Innovative open access publishing can provide avenues other than the traditional monograph or research article to disseminate research. Mosaic is a Wellcome Trust initiative that publishes longer narrative-based science journalism under the CC BY license. This license allows other platforms to take the content and republish it—with remarkable results. An article by Carl Zimmer on why we have blood types was republished on the BBC, io9, Pacific Standard, and The Independent, among others. Stories have been translated into Spanish, French, Polish, and Hungarian. The point is not just that more people read it, but that the content can be taken to the many different places where the people who are interested in this topic gather.

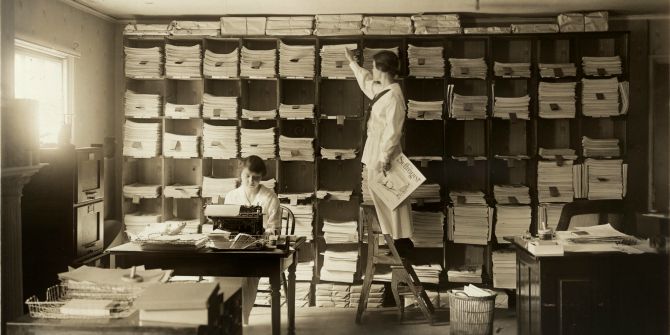

Carl Zimmer’s Pinterest Board on “Why do we have blood types?”

Carl Zimmer’s Pinterest Board on “Why do we have blood types?”

I’ve briefly illustrated why the best things in life are indeed free, but that’s slightly disingenuous because actually they’re not, and that is the biggest challenge for innovation in digital publishing. Publishers may not be able to rely on sales if they publish their monographs, research articles, or long-form journalism open access. However, the challenge is not finding the money to pay for open access, but rather flipping the way money enters the publishing system to enable publishers to innovate sustainably.

Libraries currently keep academic monograph publishing viable. Somehow we need to take the money already being spent on closed-access monographs and publish that same research open access. The challenge is clear, but the answer is not. The Wellcome Trust has made funds available to make individual monographs open access, as has the Wellcome Library for research based on its collections. Knowledge Unlatched gathers libraries together to make small, specified collections of books open access. Open Library of Humanities is looking to a Library Partnership Subsidy, with many libraries paying small amounts to make OLH articles open access. We are exploring and this is as it should be; now is the time for experimentation not consolidation.

Producing and widely disseminating high-quality research must always be the target, but there are a host of ways to achieve that. Researchers, publishers, librarians, and funders must experiment with how to get research to audiences, how to empower audiences to engage information, and how to pay for it. The best things in life aren’t free, but they are freely available.

This post originally appeared on the New York Academy of Medicine blog and is one of a series from participants in the Innovation in Digital Publishing in the Humanities session at the American Historical Association 2015 Annual Meeting in New York, co-presented by the Wellcome Trust and The New York Academy of Medicine’s Center for the History of Medicine and Public Health.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Impact of Social Science blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Cecy Marden works at the Wellcome Trust as a project manager, both for some of the Wellcome Library’s open access activity and for the Europe PMC Funders’ Group. Prior to joining Wellcome, Cecy worked at PLOS and Open Book Publishers. Her interest lies in the many facets of open access, and with a background in English and Philosophy she pays particular attention to how open access functions in relation to the humanities.

1 Comments