Adopting new tools can open up more effective ways of working and communicating research. But the new terrain can be daunting. Andy Tattersall breaks down the complexity and poses four initial questions for any researcher contemplating using some of these new tools. These questions can help ground a deliberate digital strategy and encourage researchers to prepare for the inevitable difficulties of adapting to more visible channels. But these technologies do not have to rule your work; if used correctly, they can enhance it.

The idea that all researchers, from early career researchers through to professors are engaging with the Web is pretty much a fallacy. Sure, they may use the web to search for papers, read conference proceedings and respond to funding calls; but beyond email and calendars that’s really about it for the majority. Everett Rogers’ ‘Diffusion of Innovations’ graph (below) showed that innovators and early adopters made up for just a small percentage of those who take up a new idea or technology. So it’s probably quite right that after a decade of the web moving from a read-only version to a read-write one that we would be where we are right now with regards to scholarly communication and measurement.

Source: The diffusion of innovations – Everett Rogers – Flickr Wesley Fryer – CC BY-SA

Source: The diffusion of innovations – Everett Rogers – Flickr Wesley Fryer – CC BY-SA

Much has already been written on how researchers can use the many various social, Web 2.0 and altmetric tools to communicate, collaborate and measure their work. Even so, many academics are still not sure about opening the shutters to a wider audience that transcends their institution. For any researcher contemplating using the many tools out there designed to facilitate open research there are a few questions you should ask yourself.

1. Will I respond to comments?

The web today has given anyone connected to it a voice, and that can be anyone in a variety of guises. Thankfully most communication of research appears to be open and mature. That’s not to say there are not unsavory characters in academia, but trolling happens less in these communities than say something like 4Chan or YouTube. The way to think of it is that online communities are like real world ones, you have some neighbourhoods you wouldn’t venture into after dark. So posting your work online could result in someone commenting on it. These comments might be agreeable or not, the decision you have to make is whether you want to respond to them. The answer often depends on the comment, as someone may have misquoted or misunderstood your post. They may not agree with it for a good reason and could in turn reveal new evidence for your work. It could even lead to a collaboration later on. However the main thing to remember is not to take it personally, and if it feels personal then look to contact that person outside of a public forum, via email or by telephone. The reason for this is that very few people come out of an online spat looking good. The chances are that this kind of communication is unlikely to happen, although if you are an academic who likes to court controversy read on.

2. Am I likely to get into trouble?

University researchers and lecturers have come unstuck using social media as part of their work. Contracts have been cancelled and academics told off for inappropriate comments and language using social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter. It can feel daunting to start using these tools in the knowledge that you could get into hot water over your comments. It’s quite common to see academics use the disclaimer ‘views are my own’ on a profile that links back to their organisation. In the eyes of your institution you are communicating to the world as a representative of them, so that kind of one-liner is unlikely to be a legal defence and prevent at best, a telling-off when you Tweet something objectionable about them or their students.

It’s important to remember that your professional and personal profiles can cross over using these tools. There is nothing wrong talking about your views and interests interspersed with your research, it adds an informal and human touch. There is also the option of keeping the two worlds separate, Facebook for homelife, ResearchGate for work. The main thing is to think before you Tweet or write that blog post that there is nothing wrong with stirring debate and proposing left-field ideas; after all that’s how a lot of research starts. Just remember that like driving, you shouldn’t drink and Tweet… well don’t drink too much. That what goes on the web, stays on the web and that what you think is a private comment is easily sharable by your contacts. Just remember to ‘Tweet Responsibly’.

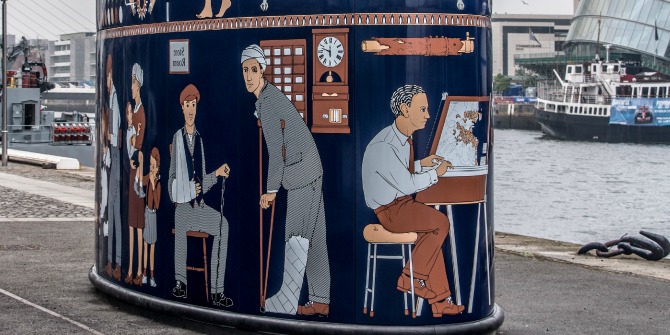

Image credit: The Internet Messenger by Buky Schwartz (Dr. Avishai Teicher CC BY-2.5)

Image credit: The Internet Messenger by Buky Schwartz (Dr. Avishai Teicher CC BY-2.5)

3. Do you have the time?

This is a common question, especially as all this communicating and measuring is just extra stuff to do, isn’t it? The reality is that many of the tools emerging around scholarly communication take a lot less time than you think. Take this blog post for example, I had the idea to write it at a conference and managed to write it in about 50 minutes. Given it’s a topic in my area of interest and expertise and that I think it could help some people I regarded it as a good use of that time. Social networking tools can be very time consuming if you let them get unwieldy and disorganised. So using tools like TweetDeck or Hootsuite for your Twitter account and such as Figshare and Altmetric.com to host and measure your outputs can reduce the labour involved for such tasks. By engaging with these tools you start to see other benefits, such as who is reading and sharing your research. Also it creates a personal learning network, that potentially leads to collaborations and the discovery of fresh ideas and research. If you are a researcher very much tied to a set way of working and feel that these tools will disrupt your flow there are things you can do. As with any distraction such as email, you can set parts of your day aside to engage with these technologies. Also, you can engage with the scholarly community using your smartphone and tablet if you have one, which allows you to work whilst in transit, at a conference or in between meetings. These technologies do not have to rule your work, if used correctly they can enhance it.

4. Am I sure I can mention my work?

There are times when a researcher cannot mention their work and this can often depend on who is funding it. It may be that the work is funded by a private company or industry and sharing it could be a breach of a research contract. It may be time sensitive or have an embargo on it, there is also the issue of it being incomplete. All of these concerns are quite legitimate, and it is always a good idea to check first if you are unsure. Nevertheless, there is always something in your field of research you can discuss and share across the Web. You may have datasets and publications that are free to be shared and discussed. Even by starting a blog to discuss your topics of interest you are putting a communication out to your research community. It might be just to discuss new research you have discovered or promote previous work that is now available for open access. Not everyone can just plough ahead and do this, and some researchers may seek guidance from a senior academic. It is helpful to see what other colleagues and departments in your institution are doing with regards to scholarly communication. If there are any seminars or training events try to get along to them as you are sure to find new ways of sharing your research as well as new contacts.

The main thing to remember that working the way you have always done may bring positive results, but they will be delivered the same old way via publication and conference. It reminds me of a quote by the brilliant Australian cricket spin bowler Shane Warne, when asked about the England bowler Monty Panesar. Warne was asked about Panesar’s record and he replied that Monty was a one-dimensional player with no variation. Warne said: “Monty Panesar hasn’t played 33 Tests, he’s played 1 Test 33 times”. By entertaining some of these tools you could discover new ways of working and communicating your research and snaffle a few extra wickets in the process.

This piece originally appeared on the Digital Science blog and is reposted with permission.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Impact of Social Science blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

3 Comments