Key perspectives and contributions – including those from queer scholars – are, in effect, written out of the discipline of political science, argues Nicola Smith. Far from being the highly multifaceted and inclusive field that it purports itself to be, political science is presenting itself in ways that marginalise the very work that is being treated as central in other social science disciplines.

Key perspectives and contributions – including those from queer scholars – are, in effect, written out of the discipline of political science, argues Nicola Smith. Far from being the highly multifaceted and inclusive field that it purports itself to be, political science is presenting itself in ways that marginalise the very work that is being treated as central in other social science disciplines.

This piece originally appeared on LSE British Politics and Policy.

Last week I turned on Radio 4 and listened to a discussion on the Today programme about child poverty, with nearly one third of children reported to be living in poverty in the UK. Interviewed on the programme was Samantha Callan, associate director at the Centre for Social Justice and former adviser on family policy to David Cameron. I was not surprised to hear one of Callan’s chief explanations for child poverty: that it is a result of ‘family breakdown’. This narrative is one that I have heard time and time before, for appeals to ‘the family’ are a defining feature of David Cameron’s political discourse.

It is through the language of the family that Cameron articulates both his vision for Britain’s economic and social recovery and, conversely, his assessment of the causes of Britain’s economic and social decline. It is the ‘hard-working family’ that represents ‘the future’ for Britain and the ‘troubled family’ that threatens such a future – as Cameron puts it: “if we want to have any hope of mending our broken society, family and parenting is where we’ve got to start”.

Yet – just as I am struck by how consistently such narratives are being articulated by Cameron and his representatives – I am also struck by how powerful, how successful, they have been. They are discourses that are used in a whole variety of contexts, including in everyday contexts, so much so that they have become naturalized and normalized over time.

I am struck by how part of their power lies not in their visibility but in their invisibility – in their repetition, so often and so widespread, that they begin to erase themselves from view. And this brings me to the queerness of political science. For the other thing to strike me about Cameron’s discourses surrounding the family is precisely how little attention they have received in the vast, diverse and ever-growing political science scholarship on economic and social crisis.

There is in fact a rich and long-standing literature from feminist and queer scholars that highlights how the supposedly ‘private’ and domestic realm of the family is not separable from, but rather is deeply implicated in, the reproduction of political and economic power relations. This scholarship interrogates how the family is not only deeply political but is also a central site upon which the structures and hierarchies of global capitalism are produced.

For feminist and queer scholars, then, we cannot bracket off the ‘personal’ sphere from questions of political, economic and social justice but rather need to (re)position this sphere as central to the study of politics. Yet, as feminist and queer scholars also note, matters surrounding intimacy and the family are systematically erased as ‘political’ matters and this is not least evident in the field of political science.

The above discussion is meant primarily as an illustration of a broader issue that, as Donna Lee and I argue in a recent article, bedevils political science. In our piece, entitled ‘What’s queer about political science?’, we contend that the construction of boundaries between the ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ of the discipline is part of the way in which political science constructs itself as a discipline. We suggest that this not only results in silences and exclusions surrounding gender, sexuality, intimacy, the family, and the body but that these silences and exclusions do important work for, as Roxanne Doty writes, ‘the margins … are themselves constitutive of the centre’.

We focus in the article on queer scholarship but could (and should) also have pointed to the systematic marginalisation of other traditions including postcolonial, critical race, trans, crip and other theories that are all centrally concerned with the critique of embodied power relations. We note that key contemporary textbooks present political science as a fairly heterodox field – including e.g. Marxism, postmodernism, some feminisms – and so a picture is painted to our students of inclusivity. Yet we also suggest that this disguises a continued preoccupation in political science with the state and that, although care is taken to equate politics with power rather than with government, the state is nevertheless positioned as the central (if not the only) site of politics/power.

This means, in turn, that other key perspectives and contributions – including those from queer scholars – are, in effect, written out of the discipline. We suggest that this is neither intentional nor the ‘fault’ of individual authors but that it is nevertheless problematic, for queer and other scholars working both within and outside of political science are busy making hugely important contributions to the study of politics and power and yet this work is often going unrecognised in the field.

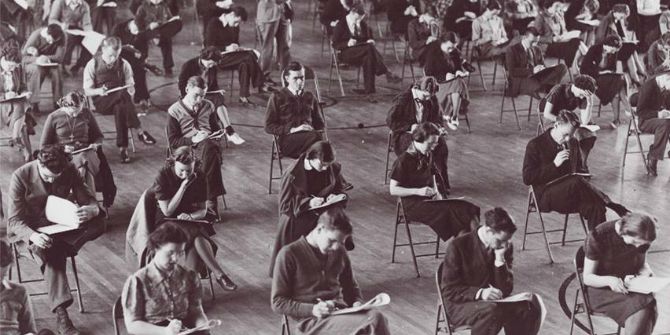

Image credit: Judith Butler (Jreberlein, GNU Free Documentation Licence)

Image credit: Judith Butler (Jreberlein, GNU Free Documentation Licence)

Ironically, our research into citation practice in the social sciences, arts and humanities finds that it is precisely work in queer theory that is particularly highly cited outside of political science. We find, for instance, that Judith Butler’s book Gender Trouble gains more citations than The Communist Manifesto and that ‘Butler’ is more cited as a standalone search term than is ‘Marx’. This implies that something queer – by which we mean strange – is going on in contemporary political science (or, more accurately, in how political science is being defined as a disciplinary terrain). Far from being the highly multifaceted and inclusive field that it purports itself to be, political science is presenting itself (to its students, at least) in ways that marginalise the very work that is being treated as central in other social science disciplines.

How can this be addressed? Queer theory itself can help. As we write:

“[W]hat queer theory does is to encourage reflection on what it means for something to be ‘political’. What gets to be constituted as ‘political’ and what doesn’t? What gets to become an object of ‘politics’ in academic enquiry and, indeed, public deliberation more broadly? What gets to be studied, discussed, contested, written about, cited, lectured on, and what doesn’t? In short: what’s in and what’s out? More than this, queer theory also insists that what gets to be counted as ‘political’ is itself political-it is a product of the exercise of power, with real material effects. In this sense, queer theory seeks to politicise ‘the political’ itself.”

Yet we would also caution against what Kath Browne and Catherine J. Nash term ‘queer fundamentalism,’ for queer theory opens up questions but resists closure in terms of concrete ‘answers,’ and so is best understood not as a theory that ‘is’ but rather as a theorizing that ‘does’ (a doing, or indeed an ‘undoing’). But we also want to be clear that there are other traditions aside from queer theory that are centrally concerned with questions of knowledge and power, and political science needs to do justice to these theories and approaches as well. For example, we would now see it as problematic that we mention postcolonial theory only in passing in our own piece – an omission that both reflects and reproduces the neglect of this crucially important work in the discipline more broadly.

Nevertheless, we very much hope that our article will help to open up (rather than to close off) space to critique, challenge and destabilize the disciplinary boundaries of political science. We would love to see a political science emerge where queer, postcolonial, trans, crip and other perspectives are taught as standard to our students; where unequal power relations along axes of gender, sexuality, race, class, dis/ability and territory are not removed from discussions of ‘politics’ and ‘power’; where the ‘private’ and intimate realms of gender, sexuality, the family, and the body are treated as always-already political; and where there is greater reflection on how processes of knowledge production are in themselves reproduction of unequal power relations. Even if we don’t go queer in political science, to do queer to political science would be a good place to start.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Impact of Social Science blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our Comments Policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

About the Author

Nicola Smith is a Senior Lecturer in Political Science at the University of Birmingham.

Once again we get another postcard from the Topsy-Turvy land where current liberal intellectual life resides. In reality, however, it’s now difficult to get an article published, across the whole social scientific field, if it is NOT about some dimension of identity politics. Of course, if identity politics were ever to admit its real dominance it would destroy its carefully coiffured self-image and lose its credibility as the ‘edgy outsider’ representing oppressed victims, challenging the boundaries of politics and so on ad nauseam. Capitalism and its broad liberal hegemonic support system loves and nurtures identity politics because it distracts attention from the real seats of concentrated power – the military-industrial complex and the global financial institutions – and thus reproduces the myth that liberal-capitalism is truly democratic and in the throes of trying to include each and every cultural group. Identity politics, fed with weak, nebulous ideas by the likes of Foucault and Butler, has killed opposition to real concentrated power – stone dead. We now live in the wreckage of effective oppositional politics, locked in a vicious battle over who are the most worthy victims and who will win concessions to ‘inclusion’ in a socioeconomic system founded upon an unforgiving form of pseudo-pacified competitive individualism. I despair whenever I am reminded of the current direction intellectual life has taken.

[sent to editor via email]

Dear Steve, thanks for engaging with my post. I know that it’s common practice to react defensively to such a comment, but I totally get your frustration. Neoliberal capitalist oppression is the ‘big issue’, and we need to fight it. I agree. So, rather than dividing, the left needs to band together. I actually see Marxist, feminist, postcolonial, queer and other such work as part of a collective project that could ‘do stuff’ if we could only stop squabbling. In fact, queer scholars tend to reject identity politics, and many openly challenge neoliberal individualism on the very grounds that you set out. So, even within this little blog space, there is the potential for alliances. I believe that we need a shared agenda for economic and social justice, and we need to find it yesterday. From your comments, I think you take the same view. So, let’s come together – isn’t that the logical extension of the points you make, that all of this must apply to us as academics too? I know academics love to be at each other’s throats, but can you imagine if we had each other’s backs instead? Can you imagine if we collectivised, not individualised, ourselves?

On collective politics: what queer and feminist scholars do is to insist that gender and sexuality cannot be excluded from this agenda. To dismiss them as ‘identity politics’ situates them as indulgent luxuries rather than as sites where unequal power relations are lived and reproduced. Queer, feminist, and also e.g. postcolonial scholars note how the failure to ‘see’ gender, race and sexuality is part of how systems of oppression are produced. (Think for example of the ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement – that is so powerful precisely because it challenges the invisibility of so many deaths). We need to ‘see’ racism, or sexism, or heterosexism, or transphobia, to be able to challenge them. To quote Audre Lorde, we need to understand that ‘there is no hierarchy of oppression’ – which is an inclusive (not exclusionary) agenda. Again, isn’t that relevant to some of the points you have made? In short, queer politics can be collective and it can form part of broader struggles for economic and social justice. So, while I don’t recognise the depiction of queer theory that you set out, I do agree with many of the underlying points you’ve made. Does that mean that we might even have a shared political project? Maybe we do – I hope so.

Anyway, even though I’d been hoping for a ‘wow – great post!’ rather than a ‘wow – terrible post!’, your comments have made me think and so thanks again for reading my post.

– Nicola Smith