An introduction has a lot of work to do in few words. Pat Thomson clarifies the core components of a journal article introduction and argues it should be thought of as a kind of mini-thesis statement, with the what, why and how of the argument spelled out in advance of the extended version. Writing a good introduction typically means “straightforward” writing and generally lays out a kind of road-map for the paper to come.

An introduction has a lot of work to do in few words. Pat Thomson clarifies the core components of a journal article introduction and argues it should be thought of as a kind of mini-thesis statement, with the what, why and how of the argument spelled out in advance of the extended version. Writing a good introduction typically means “straightforward” writing and generally lays out a kind of road-map for the paper to come.

So you want to write a journal article but are unsure about how to start it off? Well, here’s a few things to remember. The introduction to your journal article must create a good impression. Readers get a strong view of the rest of the paper from the first couple of paragraphs. If your work is engaging, concise and well structured, then readers are encouraged to go on. On the other hand, if the introduction is poorly structured, doesn’t get to the point, and is either boring or too clever by half, then the reader may well decide that those two or three paragraphs were enough. Quite enough.

At the end of the introduction, you want your reader to read on, and read on with interest, not with a sense of impending doom, or simply out of duty. The introduction therefore has to say what the reader is going to encounter in the paper, as well as why it is important. While in some scholarly traditions it is customary to let the reader find out the point of the paper at the very end – ta da – this is not how the English tradition usually works. English language journals want the rationale for the paper, and its argument, flagged up at the start.

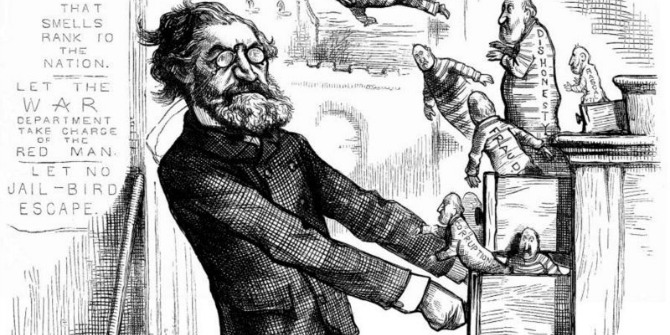

Image credit: Classical figure in robes, riding an eagle and writing on a tablet (From The New York Public Library Public Domain)

Image credit: Classical figure in robes, riding an eagle and writing on a tablet (From The New York Public Library Public Domain)

The introduction can actually be thought of as a kind of mini-thesis statement, with the what, why and how of the argument spelled out in advance of the extended version. The introduction generally lays out a kind of road-map for the paper to come. It also lets the reader know broadly about the kinds of information and evidence that you will use to make your case in the paper.

Writing an introduction is difficult. You have to think about:

- the question, problem or puzzle that you will pose at the outset, as well as

- the answer, and

- how the argument that constitutes your answer is to be staged.

At the same time, you also have to think about how you can make this opening compelling. You have to ask yourself how you will place your chosen question, problem or puzzle in a context the reader will understand. You need to consider: How broad or narrow should the context be – how local, how international, how discipline specific? Should the problem, question or puzzle be located in policy, practice or the state of scholarly debate – the literatures?

Then you have to consider the ways in which you will get the reader’s attention via a gripping opening sentence and/or the use of a provocation – an anecdote, snippet of empirical data, media headline, scenario, quotation or the like. And you must write this opener with authority – confidently and persuasively.

Writing a good introduction typically means “straightforward” writing. Not too many citations to trip the reader up. No extraordinarily long sentences with multiple ideas separated by commas and semicolons. Not too much passive voice and heavy use of nominalisation, so that the reader feels as if they are swallowing a particularly stodgy bowl of cold, day-old tapioca.

Journal article introductions – presentation from Pat Thomson

All of this? Questions, context, arguments, sequence and style as well? This is a big ask. An introduction has a lot of work to do in few words. It is little wonder that people often stall on introductions. So how to approach the writing?

In my writing courses I see people who are quite happy to get something workable, something “good enough” for the introduction – they write the introduction as a kind of place-holder – and then come back to it in subsequent edits to make it more convincing and attractive. But I also see people who can achieve a pretty good version of an introduction quite quickly, and they find that getting it “almost right” is necessary to set them up for the rest of the paper.

The thing is to find out what approach works for you.

You don’t want to end up stalled for days trying to get the most scintillating opening sentence possible. (You can always come back and rewrite!) Just remember that the most important thing to get sorted at the start is the road map, because that will help you write rest of the paper. And if you change your mind about the structure of the paper during the writing, you can always come back and adjust the introduction. Do keep saying to yourself “Nothing is carved in stone with a journal article until I send it off for publication!”

This article was originally published at Pat Thomson’s personal blog, Patter, and is republished here with permission.

Note: This article gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the LSE Impact blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Pat Thomson is Professor of Education at the University of Nottingham. Her current research focuses on creativity, the arts and change in schools and communities, and postgraduate writing pedagogies. She is currently devoting more time to exploring, reading and thinking about imaginative and inclusive pedagogies which sit at the heart of change. She blogs about her research at Patter.

And resist the urge to bloviate about the obvious, such as the global public health significance of depression when your data have a much more modest scope and focus.

Writing a good introduction typically means “straightforward” writing and generally lays out a kind of road-map for the paper to come. Where did you get this information?

Good post. I really loved the way you have explained things here. Keep up the good work.

Cheers!