Between August 2014 and September 2016, the Academic Book of the Future Project, initiated by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the British Library, explored the current and future status of the traditional academic monograph. Marilyn Deegan, one of the co-investigators on the project and author of the project report, reflects on its findings, welcoming them as an opportunity to open up further dialogue on the horizons of the academic book.

Between August 2014 and September 2016, the Academic Book of the Future Project, initiated by the Arts and Humanities Research Council and the British Library, explored the current and future status of the traditional academic monograph. Marilyn Deegan, one of the co-investigators on the project and author of the project report, reflects on its findings, welcoming them as an opportunity to open up further dialogue on the horizons of the academic book.

With pressures on academics to do more research, more teaching and be subject to ever more assessment regimes, what might the future of the academic book be? Do scholars still have the time and mental fortitude for the sustained research, reflection, and reporting that needs to go into a major monograph or critical edition? Is the move towards open access an uncontested benefit for scholars? What do massive digital developments mean for scholarship? Is reading in digital formats becoming the norm?

More books are being written all the time, but it seems that fewer are being purchased by either libraries or individuals. Whether fewer are being read is impossible to say. When books are made available online, whether open or not, many are downloaded, but this is still no guide to whether they are being read – they may be put aside for “later” like the many photocopies that probably still fill the filing cabinets of scholars. These issues are all vital for the academy, and it was to investigate these and other matters of critical importance that the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) and the British Library decided to initiate the Academic Book of the Future Project. This ran for two years from August 2014, and has launched two major reports on 20 June 2017: a project report by Marilyn Deegan and a policy report by Michael Jubb.

The project was led by Dr Samantha Rayner (UCL) as principal investigator, with the co-investigators Nick Canty (UCL), Professor Marilyn Deegan (KCL) and Professor Simon Tanner (KCL). Dr Michael Jubb was the project’s principal consultant, and Rebecca Lyons was the project’s research associate.

One of the key aims of the project was to engage as broad a community as possible, drawn from the academy, publishers, libraries, and booksellers, and we interacted with hundreds, if not thousands, of people during a two-year period. This has had an enormous multiplier effect on our work as activities snowballed as communities became engaged, and some of the activities have taken on a life of their own. One crowning achievement, Academic Book Week, has been run for a second time this year, with plans to continue into the future under the auspices of the Publishers Association, the Booksellers Association, the British Library, the British Academy, and UCL. The first university press conference took place in Liverpool in 2016; the next two are already in planning.

Besides the two reports, many deliverables been produced: blog posts, Storifyed tweets, articles and a Palgrave Pivot book. Workshops have been held, talks given, and there have been three major conferences on bookselling, on university presses, and on the situation of the academic book in the global south. We were fortunate to have the funds to commission activities and pieces of research from our community as we uncovered promising areas of investigation. This has allowed us to be agile in our approach, and some important and substantial reports have been produced for the project.

At the end of this project, we have found that the academic book/monograph is still greatly valued in the academy for many reasons: the ability to produce a sustained argument within a more capacious framework than permitted by the article format; the engagement of the reader at a deep level; its central place in career progression in the arts and humanities; and its reach beyond the academy (for some titles) into bookshops and the hands of a wider public. It seems that the future is likely to be a mixed economy of print, e-versions and networked-enhanced monographs of greater or lesser complexity. There are many new experimental partnerships between academics, libraries and publishers to push the concept of the book beyond its covers in the UK and the USA. At the same time, there is a continuing (indeed, resurgent) preference for print for sustained reading and reflection.

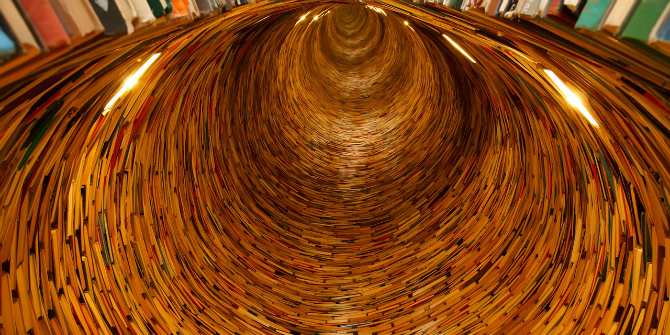

Image credit: Looking forward by robfos. This work is licensed under a CC BY 2.0 license.

Image credit: Looking forward by robfos. This work is licensed under a CC BY 2.0 license.

We have also identified a number of challenges during the course of the project:

-

- The pressure of ever-increasing teaching loads and time-consuming assessment regimes has reduced the capacity of many academics to undertake the sustained research and thinking needed to produce the very best monographs. This is augmented by the timing of REF cycles and the fact that a book only equates to two articles, despite needing much more input and time: some colleagues have suggested that a really excellent monograph or critical edition can take ten or even 20 years to complete. And most scholars would be happier producing one or two groundbreaking books in their careers, rather than five or six that are produced quickly and have less impact. However, we have been informed that many REF panels are more likely to award higher grades to books than to articles. Policymakers and institutions perhaps need to address these issues in time for the next REF.

-

- The REF panels are enjoined to be format and publisher neutral, but institutions and departments still insist that scholars publish with the more established and reputable academic and university presses. Academics themselves generally seek out publication in such venues, and the REF 2014 data showed that 46 per cent of all books submitted were from only ten publishers (out of a total of more than 1000 publishers represented), the three clear leaders being Oxford University Press, Palgrave Macmillan and Cambridge University Press. The prestige that these presses bring is still valued, despite the instructions to REF panels.

-

- While there is general acceptance among academics about the many benefits of open access, we found much confusion and anxiety about the open access agenda and the policy that open access for books will be mandated for the REF from the mid-2020s. Jubb (2017) details the many benefits and challenges; accordingly, we wish to endorse Crossick and the 2016 OAPEN Report when they suggest that open access should proceed cautiously. It also seems that the publishing world is far from ready to move into Gold open access for monographs in time for the mid-2020s; that Green open access, while possible, will only be able to offer accepted manuscripts for access rather than published versions, and that actually finding what is available in repositories is likely to be a problem.

-

- There are many forms and formats of experimental enhanced books and monographs being developed. This is to be welcomed. However, there is no certainty about which formats might become general standards (if, indeed, any should), which poses challenges for library access, delivery, discovery and long-term preservation.

The book is a durable concept. It has been around for many centuries. Its death has been predicted many times over the last few decades, but we have no doubt that in the academic world and beyond, its future is secure. But we should like to make a plea for a reduction in the pressure to produce so many books. A “never mind the quality, feel the width approach” does no service to scholarship. It seems, too, that while access to digital resources is of enormous value to the academic enterprise, monographs, especially in the humanities, still have a central place in the scholarly ecology. In print as well as digital, conventional as well as enhanced.

In short, a variety of futures for the many different kinds of academic “books”, most likely to derive from dialogue between the aspirations of the scholarly community and its funders on the one hand, and the wide range of publishers, libraries and intermediaries with expertise in the transmission of knowledge and meeting those aspirations, on the other. Bringing so many of these together to start those dialogues is what this project has been about.

This blog post originally appeared under a different title on LSE Review of Books and is published under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 UK license.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Impact Blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

About the author

Marilyn Deegan is Emeritus Professor of Digital Humanities at King’s College London and former editor of LLC: the Journal of Digital Humanities. She has over 20 years’ experience in digital humanities and is also a medievalist. Her publications include Transferred Illusions: Digital Technology and the Forms of Print (with Kathryn Sutherland, Ashgate, 2009) and Being a Pilgrim: Art and Ritual on the Medieval Routes to Santiago (With Kathleen Ashley, Lund Humphries, 2009). She is Co-Investigator of the Academic Book of the Future project, and is also a consultant to the Rwandan Gacaca Archive Digitisation Project and advisor to Digital Sudan.

I am a citizen-scholar (modern us history, electronics, old testament, religious studies, history of western philosophy) who is phasing out of owning Oxford and Cambridge monographs. I’ll probably narrow my library down to just the electronics and religious studies areas. Serious monographs of 300+ to 600+ pages weigh a ton. And I just was not referencing my reference library. Some subjects, like religious studies and electronics seem more suitable / resonant of print. While all / literally every national history has been made much MUCH more fun via the History Channel and You Tube. And as for history of western philosophy, I’ve had to admit it’s dead to all but active philosophy students.