Grant capture, or the ability of researchers to secure funding for their projects, is often used as a formal metric for academic evaluation. In this repost, Dorothy Bishop argues that this practice has led to perverse incentives for researchers and institutions and that research funders have both a responsibility and a significant interest in using their influence to halt this practice.

Grant capture, or the ability of researchers to secure funding for their projects, is often used as a formal metric for academic evaluation. In this repost, Dorothy Bishop argues that this practice has led to perverse incentives for researchers and institutions and that research funders have both a responsibility and a significant interest in using their influence to halt this practice.

I caused unease on Twitter recently when I criticised a piece in the Times Higher Education on ‘How to win a research grant‘. As I explained in a series of tweets, I have no objection to experienced grant-holders sharing their pearls of wisdom with other academics: indeed, I’ve given my own tips in the past. My objection was to the sentiment behind the lede beneath the headline: “Even in disciplines in which research is inherently inexpensive, ‘grant capture’ is increasingly being adopted as a metric to judge academics and universities. But with success rates typically little better than one in five, rejection is the fate of most applications.” I made the observation that it might have been better if the Times Higher had noted that grant capture is a stupid way to evaluate academics.

Science is in trouble when the getting of grant funding is seen as an end in itself rather than a means to the end of doing good research, with researchers rewarded in proportion to how much money they bring in. I’ve rehearsed the arguments for this view more than once on my blog (see, e.g. here); many of these points were anticipated by Raphael Gillett in 1991, long before ‘grant capture’ became widespread as an explicit management tool. Although my view is shared by some other senior figures (see, e.g., this piece by John Ioannidis), it is seldom voiced. When I suggested that the best approach to seeking funding was to wait until you had a great idea that you were itching to implement, the patience of my followers snapped. It was clear that to many people working in academia, this view is seen as naive and unrealistic. Quite simply, it’s a case of get funded or get fired. When I started out, use of funding success may have been used informally to rate academics, but now it is often explicit, sometimes to the point whereby expected grant income targets are specified.

Encouraging more and more grant submissions is toxic, both for researchers and for science, but everyone feels trapped. So how could we escape from this fix?

I think the solution has to be down to funders. They should be motivated to tackle the problem for several reasons.

- First, they are inundated with far more proposals than they can fund – to the extent that many of them use methods of “demand management” to stem the tide.

- Second, if people are pressurised into coming up with research projects in order to become or remain employed, this is not likely to lead to particularly good research. We might expect quality of proposals to improve if people are encouraged to take time to develop and hone a great idea.

- Third, although peer review of grants is generally thought to be the best among various unsatisfactory options for selecting grants, it is known to have poor reliability, and there is an element of lottery as to who gets funded. There’s a real risk that, with grant capture being used as a metric, many researchers are being lost from the system because they were unlucky rather than untalented.

- Fourth, if people are evaluated in terms of the amount of funding they acquire, they will be motivated to make their proposals as expensive as possible: this cannot be in the interests of the funders.

Funders have considerable power in their hands and they can use it to change the culture. This was neatly demonstrated when the Athena SWAN charter started up, originally focused on improving gender equality in STEMM subjects. Institutions paid lip service to it, but there was little action until the Chief Medical Officer, Sally Davies, declared that to be eligible for biomedical funding from NIHR, institutions would have to have a Silver Athena SWAN award. This raising of the stakes concentrated the minds of Vice Chancellors to an impressive degree.

My suggestion is that major funders such as Research England, Wellcome Trust and Cancer Research UK could at a stroke improve research culture in the UK by implementing a rule whereby any institution that used grant capture as a criterion for hiring, firing or promotion would be ineligible to host grants.

This post originally appeared on the author’s personal blog, BishopBlog and is reposted with permission.

About the Author

Dorothy Bishop is Professor of Developmental Neuropsychology and a Wellcome Principal Research Fellow at the Department of Experimental Psychology at Oxford. The primary aim of her research is to increase understanding of why some children have specific language impairment (SLI). Dorothy blogs at BishopBlog and is on Twitter @deevybee

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Impact Blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below

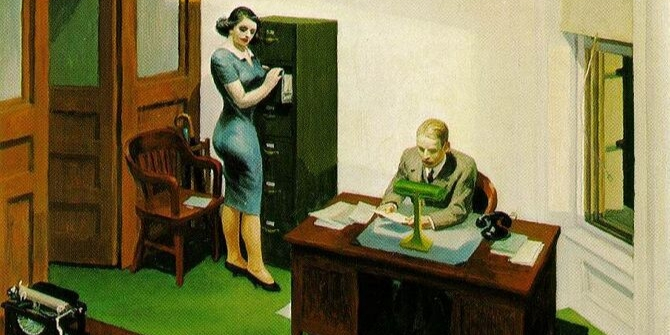

Featured Image Credit, Jeffery Wong via Unsplash.

Whereas universities might be most interested in how much money researchers can bring, funding agencies ought to be more focused on what researchers can do with their funds, their “impact per dollar” (or pound, or Euro..). Researchers ought not be admired and rewarded simply because of the size of their grants, but rather by whether they know how to use them.

Great to address this topic, I share your concerns! We have reported this phenomenon in a recent publication about the scientific reward system, where we found that researchers receive recognition for acquiring prestigious grants: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11024-018-09366-x

In the so-called credibility cycle this creates a feedback loop between money and recognition.