Discussions about research impact are often littered with particular language that serves to demonstrate how different forms of impact are valued, promoted and sustained. Drawing on evidence from qualitative datasets, comprising interviews with researchers and research impact evaluators, Jennifer Chubb and Gemma Derrick argue that the language of research impact and assessment is frequently structured along gender lines, and that this is both unhelpful to the generation and evaluation of research impact in and of itself, but also to the development of an inclusive, diverse and supportive research culture.

You may not have heard about the impact a-gender, but the chances are you have encountered it in water-cooler conversations, university corridors, or the formal settings of meetings and review panels…

By this, simply put, we mean the implicit and explicit gendered associations often drawn when academics refer to types of impact activities and how this can creep into the evaluation of impact. Previous work by Yarrow and Davies has shown that women were significantly less likely to be the authors of impact case studies in the 2014 round of the UK’s Research Excellence Framework (REF). Our own research reinforces this observation, revealing how gendered assumptions toward impact and its assessment play a significant role in all aspects of research impact; from deciding what kinds of research impact receive attention, to the way in which REF panels codify and assess the quality of research impacts.

binary associations are integral to the way gender bias infiltrates academia generally, but here we see this association towards non-academic impact

To explore how gender might underscore thinking about research impact, we re-evaluated two independent datasets to examine the ways in which impact was described in both the generation and evaluation of research impact: the first containing semi-structured interviews with mid-senior academics at two research-intensive universities in Australia and the UK, collected between 2011 and 2013 (n=51); and the second including pre- (n=62), and post-evaluation (n=57) interviews with REF2014 Main Panel A (medicine, health and life sciences) evaluators.

We found that gendered perceptions of research impact to run deep and that regardless of a participant’s gender, unconsciously assigned gendered orientations to impact activities were attributed to research impact that were then repeated during evaluation. We call this process, by which gendered notions of non-academic, societal impact and how it is generated feed into its evaluation, the impact a-gender. Left unchecked, this risks compounding gender inequality in academia; creating an additional ‘Matilda effect’ for research impact, whereby the achievements of female researchers are further marginalised.

Gendered definitions of impact

The gendered nature of impact begins with defining impact itself. For example, during our interviews, researchers in the UK and Australia used terms such as ‘hard’ (masculine) or ‘soft’ (feminine) when talking about the types of impact created and these were prevalent alongside gendered notions of excellence related to competitiveness. These binary associations are integral to the way gender bias infiltrates academia generally, but here we see this association towards non-academic impact. When referring to impact more generally, it was not necessarily the masculinity or femininity of the researcher that was emphasised, but rather the activity used to generate it. ‘Soft’ impact activities were described as;

“Stuff that’s on a flaky edge – it’s very much about social engagement” (Languages, Australia, Professor, Male).

Researchers placed value on hard over soft impacts, referring to how soft impacts were of less value to institutions and amongst their colleagues. Even the word impact itself, is to some extent burdened with gendered connotations of ‘force’ and ‘weight’.

Gendered sorting of impact activities

When asked about engaging in Impact, both men and women were dissuaded (by inner narratives, institutions, or by colleagues) from engaging in impacts that were not conducive to ‘hard’ impacts. Researchers reported being pressured away from non-gender-acceptable forms of impact, either in preference to other more masculine notions of academic productivity (for men), or towards soft notions of academic productivity i.e. public outreach (for women).

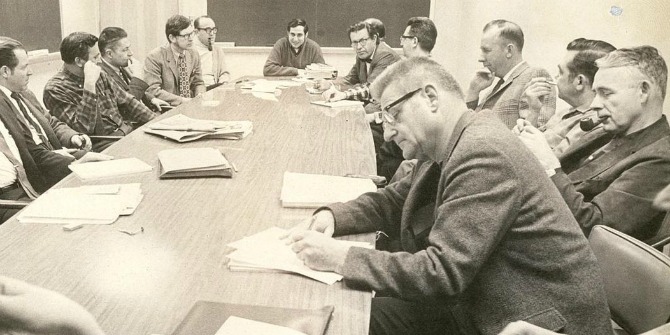

In practice, some men, in particular, implicitly referred to women as better with the ‘soft and woolly’ impacts and justified this based on a sense of ‘duty’ or ‘public service’ associated with the nurturing role commonly assigned to women. This immediately and implicitly assigned certain types of impact activities to women, such as public engagement, while the more dominant, activities that lead to economic impacts, such as technology transfer, relating less to people and more to things i.e. licensing or spin-outs, were more likely to be assigned to men. When the reason behind this association was explored, gendered notions of competitiveness emerged: (talking about public engagement) “women are better at this! They are less competitive!” (Environment, UK, Professor, Male). Women were perceived as not sufficiently competitive for ‘harder’ impacts, despite having already been steered away from engaging in these activities.

Gendered evaluations of impact

In a further extension of the impact a-gender, these gendered associations of Impact were echoed by Impact evaluators. Here, despite a shift away from impact and measurement, the types of impact that are not as easily measurable and are, by nature, more amenable to qualitative narratives around societal and cultural value, were again characterised as ‘soft’. In contrast, quantifiable impact was often masculinised and more regularly depicted as ‘hard’. For instance, when articulating impact, male evaluators were more likely to express impact as causal and linear, involving a single “star” or “champion”, who delivered it from start (underpinning research) to finish (impact). So too, when these binary interpretations were present, they were more likely to value impact in a way in which encoded perceptions of hard/ quantifiable/ masculine research (as opposed to soft/ qualitative/ feminine) were considered as being higher quality and of more esteem, regardless of the actual quality of the research or its impact.

Male and female evaluators also conceptualised impact differently for the sake of its evaluation. Female evaluators were more open to and expressed sensitivity towards the complexity of impact and this included taking into account issues of time-lags, reasons for the lack of causality (especially for policy impacts) and reasonable attribution claims. Male evaluators, on the other hand, strived to conceptualise impact as excellent if it was a “straight -forward” and “measurable change”.

Gendered evaluators of impact

Finally, evaluators also suggested that the workings of the panel during the evaluation were also drawn down gendered lines. If accurate, this risks silencing conflicting opinions that may call for a more complex approach to Impact evaluation. In this way, women were valued as panel members if they played a supportive, supplementary role and were a good “team player”;

“A good panel member was — someone who is happy to listen to discussions; to not be too dogmatic about their opinion, but can listen and learn, because impact is something we are all learning from scratch. Somebody who wasn’t too outspoken, was a team player.” (Panel 3, Outputs and Impact, Female)

Calling out the impact a-gender

Our research suggests that notions of soft and hard impact are not simply benign, but can serve to marginalise individuals, groups and particular kinds of research. What we have uncovered, we fear, only scratches the surface of some of the ways in which an impact a-gender emerges within the academic community, and evaluation panels. However, its implications will be familiar to many researchers preparing REF case studies, and to policymakers that are working to ensure that the REF evaluation process is free from these implicit biases.

What we must do, as a community, is reflect on our scholarly norms of intellectual practice; to be skeptical about our own preconceptions and attitudes which come as second nature and to question our assumptions and prejudices. Individually, we must continually and explicitly check our own behaviour to minimise any further follow on effects. This is regardless of whether we work as researchers generating impact, or as evaluators assessing it.

The impact a-gender is known and it is not acceptable. Let’s not leave it unchecked.

This post draws on the author’s co-authored paper, The impact a-gender: gendered orientations towards research Impact and its evaluation, published in Palgrave Communications.

Image credit: Viktor Talashuk, via Unsplash.

Thanks for a very insightful and powerful analyses. Thank you also for the call for action and activism in research practices.