In Being Well in Academia: Ways to Feel Stronger, Safer and More Connected, Petra Boynton provides a practical guide to how to recognise and confront the various issues that can arise from being in academia. Through Boynton’s sensitive approach to academic self-help, the book offers a succinct overview of the challenges that can be thrown at those studying or working in academia and a useful toolkit for addressing them, finds Chris Featherstone.

This review originally appeared on LSE Review of Books. If you would like to contribute to the series, please contact the managing editor of LSE Review of Books, Dr Rosemary Deller, at lsereviewofbooks@lse.ac.uk

Being Well in Academia: Ways to Feel Stronger, Safer and More Connected. Petra Boynton. Routledge. 2020.

The mental health crises in academia have been a topic of comment for years, and whilst COVID-19 has worsened this situation, it has been decades in the making. In Being Well in Academia, Petra Boynton offers a toolkit for students and academic staff alike, sensitively providing advice on how to recognise issues and what to do about them.

The mental health crises in academia have been a topic of comment for years, and whilst COVID-19 has worsened this situation, it has been decades in the making. In Being Well in Academia, Petra Boynton offers a toolkit for students and academic staff alike, sensitively providing advice on how to recognise issues and what to do about them.

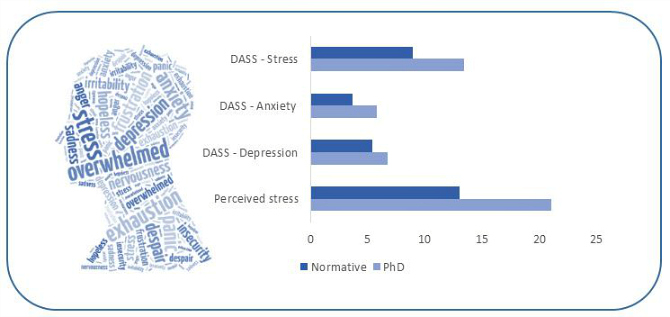

The crisis in the mental health of academic staff is well-known and has been described as an ‘epidemic’. Similarly, there is a body of research that outlines the crisis in the mental health of PhD students. Katia Levecque et al (2017) found that one in two PhD students self-reported experiencing psychological distress, and one in three was found to be at risk of a common psychiatric disorder. Crucially, Levecque et al argue that the work and organisational context was a significant predictor of PhD students’ mental health. Teresa Evans et al (2018) gave further evidence of this mental health crisis amongst PhD students, showing that 40 per cent of their respondents’ anxiety scores were between moderate and severe, and almost 40 per cent of respondents showed signs of moderate to severe depression. Most recently, Advanced HE’s Postgraduate Research Experience Survey showed that only 14 per cent of respondents reported they had low anxiety; everyone else reported higher levels. After Nature ran a story covering an international survey that demonstrated the mental health crisis amongst PhD students, more than 150 PhDs reached out with their stories.

The mental health crises in academia have been a topic of comment for years, and whilst COVID-19 has worsened this situation, it has been decades in the making.

The undergraduate mental health crisis is no less serious. In a 2016 YouGov survey, one in four students had a self-diagnosed mental health issue. Similarly, in a 2018 survey, one in five students had a mental health issue, and one in three had a mental health issue for which they had sought professional help. The COVID-19 crisis is reinforcing this: a 2020 survey by the Guardian showed 57 per cent of students polled said their mental health has worsened since the start of the academic year. Further, 63 per cent said COVID-19 was a great risk to their mental health.

In the context of this crisis, Boynton’s book is a timely contribution that is badly needed. There are plenty of resources available that can tell students and academic staff what to do, but where this book is different is that Boynton shows the reader how to do the advised self-help activities. Personally, I am not used to using this form of self-help book, yet I found the format helpful and the activities effective. The book takes the reader from understanding the issues, to recognising the issues that one faces and how to both help oneself and others. In the introduction to the second chapter, the activity ‘Be kind to yourself’ gently steers the reader through several scenarios of unkindness. In doing so, the book then demonstrates the ways that we can be unkind to ourselves, by ignoring our own feelings or dismissing our needs (hunger, sleep, etc).

The book begins with a trigger warning, outlining topics that may be difficult to read for some of those using the book. The user’s guide that follows is not typical in academic works; however, it is particularly useful given the purpose of this book. Networking is the general topic of the second chapter, beginning with positioning and caring for oneself as an individual. The chapter then proceeds through advice on how personal relationships (friends and family) and professional relationships (peers and colleagues) can be used to ‘be well’ in academia, before looking at professional organisations and social media. The chapter provides interesting guidance on how to navigate academia, with particular advice aimed at people from URM (Under-Represented Minorities) at all levels (students, early career researchers, academic staff, etc).

The third chapter in particular, ‘Giving and Receiving Care’, should be considered required reading by students and academic staff alike. This chapter especially shows how this book speaks to a variety of audiences within academia, giving advice on how to both receive and give care. The advice on how to establish the appropriate conditions for receiving care (the ‘right person’, ‘right time’ and ‘in the right way’) and the suggestions for people who do not feel able to reach out for help are incredibly useful. Another stand-out section of this chapter is titled ‘How to spot if a friend or colleague is in crisis’, and in light of the statistics on the mental health crisis in academia outlined at the beginning of this review, this is crucial advice.

The third chapter in particular, ‘Giving and Receiving Care’, should be considered required reading by students and academic staff alike.

Academia’s well-known issues with diversity and inclusion mean that the advice on being an ‘active bystander’ is another valuable contribution of this book. The section starts with a list of unacceptable behaviours and reading this is an uncomfortable experience. The list is comprehensive, and what makes it particularly uncomfortable to read is how readily I believe that these behaviours do occur in academia. Several are worryingly visible (#Manels, #Wanels), whereas others form part of many people’s experience of academia (unpaid work, unfair contracts). The ‘ABCs’ that Boynton outlines (assess the situation, be in a group, care for the victim and check they are OK) provide a useful reminder of how everyone in academia can act to prevent such unacceptable behaviours re-occurring. The ‘Four Ds’ that follow the ‘ABCs’ provide essential advice on how to approach situations where unacceptable behaviours are happening, emphasising both safety and wellbeing.

With Being Well in Academia, Petra Boynton achieves her goal brilliantly. This book provides a sensitive take on academic self-help. The advice covers what to do if you feel academia is impacting your mental health and shows how you can take steps to address this through a variety of activities. The book synthesises advice on how to look out for your own and other’s wellbeing with guidance that can be used to navigate an academic career. This book should not be regarded as something to read solely to help with mental health or wellbeing; it should be read at intervals to help the reader navigate their path in academia more generally. Petra Boynton has provided an essential toolkit to help confront the various crises in academia, which have only been exacerbated by COVID-19.

Note: This review gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Impact Blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: Agnieszka Ziomek via Unsplash.

1 Comments