The aggregation and linkage of data collected by different public services can often be presented unproblematically as a solution to various social issues, notably so in the last year in response to the public health crisis of COVID-19. Drawing on new survey evidence, Rosalind Edwards, Val Gillies and Sarah Gorin¸ suggest greater care should be given to the social implications of extensive data linkage and the way it is differentially perceived and experienced across social groups.

The COVID-19 pandemic has accelerated calls for public services to share and join-up their administrative data sets. The UK’s recent National Data Strategy demonstrates how data linkage has been essential for public health responses, while the House of Lords Select Committee on Public Services has underlined this for public services working with children and families specifically. However, advocates of extensive joining up of public records to support service interventions often regard data and its collection as neutral, without recognising how they can reflect and intensify the social inequalities they capture.

Indeed, at the same time as presenting a case for the increased centralization of data, the pandemic has also revealed stark social, educational and material inequalities, and a lack of trust in public institutions among marginalised groups. Not only are social groups positioned differently by data, they also are likely to regard the collection and use of their administrative records quite differently, running the risk of further marginalising some groups.

on the whole, parents find the joining together of administrative records of their children acceptable, but they are more circumspect about the specifics of trusting particular public services to do this

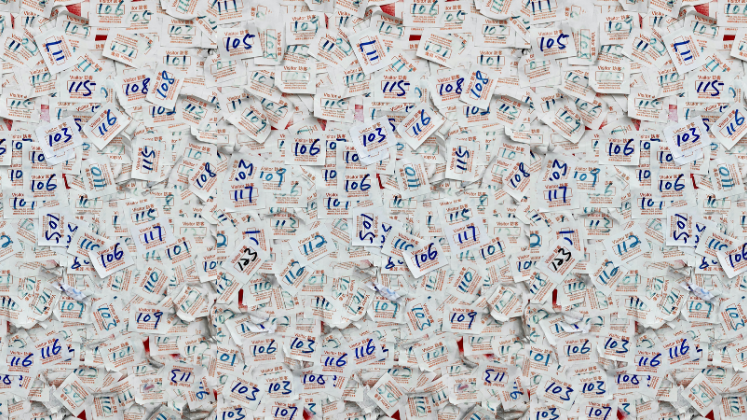

Legal authority to share and link data does not automatically command social licence – that is, social trust and acceptance of the legitimacy of practices that lie outside general norms. Our Parental social licence for data linkage project for service intervention project attempts to provide a wider understanding of social legitimacy for data linkage and analytics among parents of dependent children. To what extent does this practice of using data to guide service intervention lie within social acceptance norms, and how much trust is there? The integration and analysis of administrative records from public services includes the use of data about all families, so as part of our research NatCen carried out an online and telephone survey involving just under 850 parents of dependent children across the UK.

We found that, on the whole, parents find the joining together of administrative records of their children acceptable, but they are more circumspect about the specifics of trusting particular public services to do this. At the general level, identifying families that might need support, catching problems early on, efficiently targeting services, identifying risk of child abuse, and so on, were seen as acceptable reasons for joining together administrative records, with over 80% of parents agreeing. But, the picture changes when it comes to considering the use of data linkage by specific public services, such as: children’s social work teams, local council education services, early years services, and police and criminal justice. Only around half of parents overall said they trusted each of these services to join together administrative records to identify families to target public services at. Importantly, though, the picture varies between different social groups of parents.

Acceptance of data linkage and analytics, and trust in services to join together administrative records was stronger among parents in managerial and professional occupations, with higher levels of qualifications and higher incomes, but there is less social licence for operational data linkage among marginalised social groups of parents. Notably, less than half of Black parents trust any public services concerning their use of data linkage, especially not police and criminal justice, and immigration services where it drops to under a third. They feel that information collected about services users is not always accurate (79%), that data linkage will lead to discrimination against some families (57%), and that it can put families off accessing services when they need them (62%). One Black parent wrote in an open comment box: ‘They don’t need to be in our business’.

Other marginalised social groups, such as the least well off, lone parents, younger parents, and parents in larger families also show low levels of trust in data linkage by many public services for similar reasons. This points to a worrying level of distrust toward government and public services among those in society who are most marginalised and whose families are likely to be identified for service interventions.

This lack of social legitimacy should be a concern for policy prescriptions about sharing and linking families’ administrative records, especially in the light of parents’ knowledge of data linkage and views about transparency. Transparency and informed consent to use of their family administrative records is important for parents of dependent children. But they do not agree that families generally know or understand how their administrative records are used (60%), and overwhelming feel that Government should publicise how they link and use families’ data (81%). There is a strong view that parents need to be asked permission for administrative records about their family to be linked together (60%), which is even higher among Black parents and lone parents (each at 66%).

policy-makers also need to realise that information about this use of data and efforts towards obtaining informed consent are likely to be received and judged quite differently among different social groups of parents

Government needs to be transparent about how they link and use families’ data and to gain parents’ informed consent. But policy-makers also need to realise that information about this use of data and efforts towards obtaining informed consent are likely to be received and judged quite differently among different social groups of parents. Generalised messages and initiatives have the potential to bolster already existing trust among parents in the higher occupation, qualification and income group, while running the risk of engendering further disengagement among marginalised social groups of parents, for example active avoidance of essential health and education services, etc.

It is vital to pay attention to the extent of social licence and trust in data linkage among marginalised groups of parents in society. Implementation of sharing and linking of data amongst public services working with children and families has the potential to further undermine social legitimacy and trust, with consequences for a cohesive and equal society.

The Parental social licence for data linkage project for service intervention is funded by the UKRI Economic and Social Research Council under grant number ES/T001623/1

Note: This review gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the LSE Impact Blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: Adapted from Andrea Piacquadio via Pexels.

2 Comments