Alt-text is an important and increasingly required element of online publishing that provides accessibility to visual images for those using screen readers to listen to digital publications. Reflecting on a recent experience when writing up her PhD thesis, Lettie Y. Conrad discusses the value of author produced alt-text for images in academic writing and shares resources and a three-step guide for authors looking to improve their alt-text practice.

On an ordinary Wednesday afternoon, my academic and professional lives came crashing together in a spectacular demonstration of the importance of accessible publishing.

You see, I am a full-time publishing consultant, specialising in digital product research and design. In my work to optimize users’ experiences in the scholarly workflow, I often help publishers ensure their content is accessible to readers with limited sight, hearing, mobility, or other disabilities — for instance, designing content to be compatible with screen readers.

In my spare time, I am also an independent researcher and information science Ph.D. candidate, focused on understanding the information experiences of students, instructors, researchers, and others in the global scholarly community. I am at the final stages of my doctorate, preparing my thesis for external review, which involves cleaning up formatting and double-checking citations.

On that ordinary Wednesday afternoon, while working on my thesis, I noticed the new accessibility tools in Microsoft Word generated “alternative text” (alt-text) for my photographs. I was thrilled to see this new feature! Especially integrated into such a dominant content application. And I was pleased that I could easily edit this new field. However, I was unhappy with the automated results. Allow me to demonstrate.

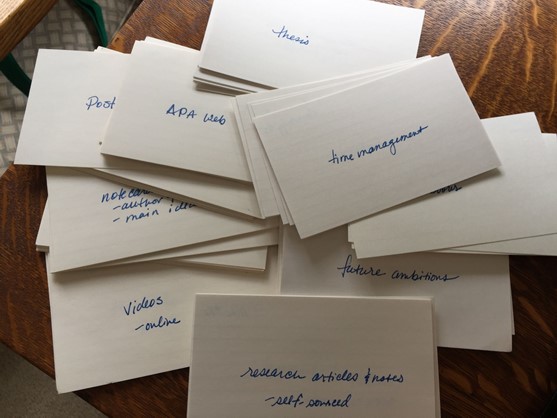

The photograph below appears in my thesis to depict the 3×5 cards I used in both my data gathering (where qualitative interviews included card-sorting activities) and in my data analysis (where I sorted duplicates of those same cards while coding). What you see in this image are the duplicate cards I created to represent those generated by interview participants.

However, the commentary automatically generated by MS Word was simply: “A picture containing text, business card.” For someone who has devoted many hours of my life to developing, executing, and discussing the importance of card sorting in my research design, this description is, at best, useless, at worst, misleading.

In that moment, I was struck by the power of authorship in this digital age. Now, more than ever, researchers of all kinds have the ability — and therefore the responsibility — to empower our scholarly outputs with the type of information that only we, as authors, can provide: namely, image descriptions.

Yes, in-text descriptions and captions appearing alongside figures, diagrams, and photographs are a must — but they are often brief and incomplete. In this case, my caption for this image was “Photograph of proxy versions of the original cards created and sorted by participants” – clearly, written with the assumption that readers can see my photograph as well as surrounding text.

So, I crafted a fuller description of my image, intended for those who cannot see it as I can, which could serve as a stand-in for the photo. I replaced the imprecise Word-generated text with, “A photograph of approximately 100 white index cards, loosely stacked, handwritten with terms such as ‘thesis,’ ‘time management,’ and ‘videos.’ These are called ‘proxy cards,’ as they are copies of the cards created and sorted by interview participants (to preserve the original artifacts).” See the difference?

Without rich and accurate descriptions, images are lost to those relying on screen readers or other text-to-speech applications. Those images are also obscured to users of search features within databases, reference managers, and other research tools. Those images can also be lost to future readers who may not have the necessary software or hardware to access the original versions of our works. Only human-generated image descriptions, ideally supplied by the author(s) themselves, can unlock the type of accessibility, searchability, and archivability today’s digital scholarship demands.

So, dear reader, this is my call to action for all authors and researchers: The next time you insert a non-decorative image into a manuscript intended for any sort of publication or wider dissemination, please remember 3 easy steps:

- Contextualize the image for readers, considering what information would be missed if your table, graph, or photograph was not visible.

- Craft a short (max. 250 characters) and complete description to characterize and explain your image (see more in the resources below).

- Connect your description to the image file (see help pages like this for tips).

Where scholarly publications include image descriptions written by the original author(s), a wider range of readers will have access to your work, which will also be more easily searched and archived. While the ideas are fresh, capture that alt-text and insist your publishing partners make good use of these assets. Your future readers thank you!

Recommended resources:

- Cooper Hewitt: guidelines for image descriptions

- Harvard: write good alt text to describe images

Acknowledgments: Many thanks to numerous experts who have helped me better understand the value of author-generated image descriptions — in particular, Becky Graham, Mimosa Shah, Caroline Desrosiers, and others who chimed into this recent Twitter conversation.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Impact Blog, nor of the London School of Economics. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Reproduced with permission of the author.

3 Comments