Jess Crilly introduces the new collection Narrative Expansions (Facet Publishing), co-edited with Regina Everitt, which brings together contributors to document recent work to decolonise the library and archive.

This blogpost originally appeared on LSE Review of Books. If you would like to contribute to the series, please contact the managing editor of LSE Review of Books, Dr Rosemary Deller, at lsereviewofbooks@lse.ac.uk.

Expanding the narrative in libraries and archives

Narrative Expansions is a collection of essays that document recent work to decolonise the library and archive, frequently as part of wider institutional moves to decolonise the curriculum. The book explores the role of the university in European colonial expansion, creating hierarchies of knowledge, and how this in turn has shaped the academic library. At the core of the book is the concept of knowledge justice, or epistemic justice – who has the status of knower, what narratives and forms of knowledge does the academic library validate, who does it exclude?

Narrative Expansions is a collection of essays that document recent work to decolonise the library and archive, frequently as part of wider institutional moves to decolonise the curriculum. The book explores the role of the university in European colonial expansion, creating hierarchies of knowledge, and how this in turn has shaped the academic library. At the core of the book is the concept of knowledge justice, or epistemic justice – who has the status of knower, what narratives and forms of knowledge does the academic library validate, who does it exclude?

As editors, we acknowledge the tensions and risks of working in this area, typified by the frequent use of ‘decolonisation’. These commas act as shorthand for the problematisation of the term – the risks of weakening the radical intention of decolonisation; of reducing it to a buzzword; of over-claiming. These are real tensions that librarians acknowledge whilst seeking to address the multiple impacts of imperial histories on the library and knowledge production.

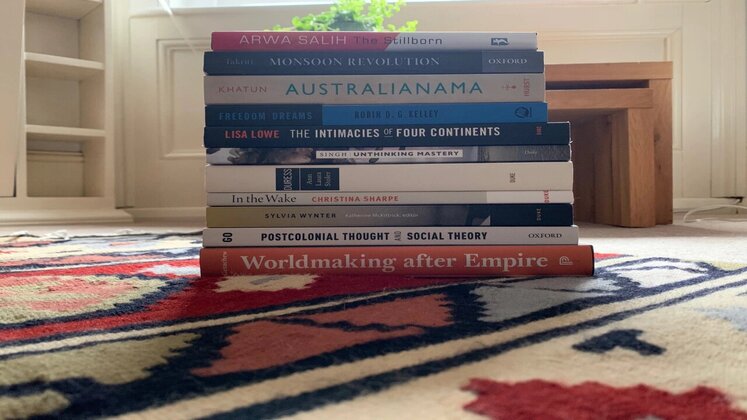

The case studies focus on many aspects of scholarly communication, academic publishing and the organisation of libraries, systems that by default privilege authors and narratives from the Global North. The need to address the Whiteness of library and archive staffing is a recurrent theme, as is the need for effective allyship. Much of the work taking place in libraries and archives is centred on collections, filling in gaps and omissions and building more plural narratives, working with staff and students on broadening reading lists (in terms of authorship, content, format, place of publication, institutional affiliation). However, the book also considers the related areas of decolonising research methodologies and offers a template for adding decolonisation to the LIS (Library & Information Science) curriculum.

There is considerable ongoing effort given to examining the legacies of classification systems and terminology such as ‘subject headings’.

There is considerable ongoing effort given to examining the legacies of classification systems and terminology such as ‘subject headings’. The major schemes in use, such as the Library of Congress Classification and Subject Headings and the Dewey Decimal Classification, were first published in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Despite a constant process of revision, their origins and inherent universalising nature mean they continue to produce categories of ‘the other’, especially in relation to gender, sexuality, ethnicity and indigenous ways of knowing and being. Change to these internationally adopted systems presents both logistical and philosophical challenges to libraries, and some have developed alternative schemes.

The book was written in the era of Trumpism characterised by widespread conspiracy theories, disinformation as well as anti-expert and anti-science sentiment. The case studies also describe examples of critical pedagogy and critical information literacy, including sharing with students the constructed and historically biased nature of discovery systems, in libraries and in information systems more widely.

Narrative Expansions also recognises the lived experience of racially minoritised students and staff in our institutions and their perceptions of how the library can either exacerbate feelings of exclusion or be a powerful resource and space for belonging.

The book is international in scope, and the authors describe the complexities of their specific colonial histories and geographies. There are case studies located in several university libraries in the UK (Cambridge, Goldsmiths, SOAS University of London, LSE and University of the Arts London). There is also an important account of recent work by staff at the British Library, an organisation with a unique history and role in the UK’s knowledge infrastructure. The settler colonial context is articulated by librarians in Canadian universities. Their roles focus on indigenisation and they are working in the context of the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission and its Calls to Action that recognise the problematic history of education as a colonial tool, the need for reconciliation, and are contributing to the indigenisation of curricula and research methodologies.

The study of libraries in Nairobi, Kenya, presents a post-colonial context, using a case study of the historic McMillan Library. This was founded in 1931 for Europeans only, handed over to Nairobi City Council in 1962 and is now under the management of The Book Bunk Trust. What does decolonisation mean in this context, and how should the library deal with the literature of the past, so as not to simply ‘forget and move on’ but retain the history of anti-colonial struggle and future visioning?

Shared experiences resonate through the book, of libraries across the globe in different historical contexts now dealing with similar legacies. The role of the academic library in the formation and institutionalisation of disciplines (area studies, geography and so forth) is also evident, and now in the ongoing re-contextualisation of those disciplines. This book is hopefully a springboard for further connections.

Shared experiences resonate through the book, of libraries across the globe in different historical contexts now dealing with similar legacies.

During the period of writing the book in 2020-21, the decolonisation movement in UK Higher Education felt like part of a wider contested struggle over historical narrative, with events including the publication of The Brutish Museums and its call for restitution of the looted Benin Bronzes, the National Trust publication on colonialism and historic slavery, the toppling of slave-trader Edward Colston’s statue in Bristol and, more recently, antagonism to critical race theory (used by several authors in the book), particularly in the United States. The longevity of this project and its impacts are yet to be determined, but the movement to decolonise libraries is very much about expanding the narratives of our past and present through the myriad of perspectives of people of different genders, ethnicities and abilities in both the Global South and North.

Jess Crilly is an independent author, and has worked mainly in academic libraries, most recently as Associate Director for Content and Discovery, Library Services, University of the Arts London, up to September 2020. Jess’s interests include critical librarianship, the meanings of and possibilities for the decolonisation of knowledge, and the multiple contexts and uses of archives.

Regina Everitt is Assistant Chief Operating Officer (ACOO) & Director of Library, Archives and Learning Services at the University of East London. She began her professional career as a technical author/trainer working with computer companies that developed software for the manufacturing, pharmaceutical and financial sectors in the US and UK. After managing a small library at a university in West Africa as a volunteer with the United States Peace Corps, she transitioned into the HE sector developing and managing libraries, social learning spaces, and other learning resources. At University of East London, she is institution lead on excellence in customer service delivery.

Image Credit: Andrea Fickl via Unsplash

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.