Reflecting on work uncovering the colonial genealogies of foundational works in the social sciences, Gurminder K Bhambra argues for a reparatory social science and highlights three challenges that any reparatory project must face in order to be successful.

Sociology, and the broader social sciences, are shaped by the idea that the ‘modern’ world is their special domain of investigation. It is contrasted to a ‘non-modern’ world that is seen to be the concern of anthropology, and a ‘pre-modern’ world that is typically the concern of historians. However, this modern world is a colonial world, albeit that colonialism and empire are largely absent from the social sciences.

If standard accounts have elided the relationship between colonialism and modernity, then accounting for this relationship requires us also to transform sociology. Here, I draw out the key concerns of a reparatory sociology that follow once the role of colonialism in the shaping of the modern world is recognised. I do this by building on work both within and outside the academy.

If standard accounts have elided the relationship between colonialism and modernity, then accounting for this relationship requires us also to transform sociology.

Notably, a reparatory sociology must recognise the significant claims for reparations made by activists now and in the past. This includes the significant work of Hilary Beckles, CARICOM, and Rastafari Movement UK, in the context of slavery and indigenous dispossession in the Caribbean; and that of Shashi Tharoor and earlier figures such as Dadabhai Naoroji in relation to colonial drain from the Indian subcontinent. It is activism such as this that has brought about academic engagement with the idea of reparations for colonialism.

The issue of slavery and Black experience, in particular, was the focus of a research symposium on ‘Reparative Histories’ organised by Anita Rupprecht and Cathy Bergin and published in Race and Class in 2016. This was followed by articles by Colin Prescod and Catherine Hall addressing the relationship between calls for reparations, the archive, and the writing of history itself.

The question of reparative futures has been picked up Arathi Sriprakash and colleagues who seek to rethink the relationship between the past and futures oriented to questions of repair and justice. Olúfemi O. Táíwò similarly argues for reparations to be seen as a future-oriented project; one that develops a constructive view of reparations rooted in philosophical concerns of distributive justice.

Over the last couple of years, I have sought to examine these issues through and for the social sciences (see my May 2021 talk at the LSE and subsequent journal article). A reparatory sociology, I suggest, requires a reconsideration of the histories that are taken to be central to it as well as a reorientation of our conceptual understandings as a consequence. It further requires us to be committed to epistemological justice in our practices. Here I identify three crucial challenges:

Historical

European modernity, organised in terms of the industrial revolution and the French revolution, has long been argued to be the central defining frame for the social sciences. However, much research has argued for the necessity of addressing the global conditions of these events as well as acknowledging other world historical processes and, indeed, the interconnections between them.

Arguing for the histories of Europe to be understood as colonial histories is an inclusive move that seeks to account for the shape of Europe (and the world) today as a consequence of global practices of domination and appropriation. It is these histories that have produced the modern world and need to form the basis from which we rethink the social sciences, including sociology.

Conceptual

The nation state is proposed as a primary unit of analysis across the social sciences. The period that is seen to give rise to the modern nation state, however, is precisely a period of colonial expansion that saw some European states consolidate their domination over other parts of the world within imperial formations. Yet, what is seen as ‘external’ domination is rarely theorised as a constitutive aspect of the ‘modern state’.

The argument that we should move from using the nation as the unit of analysis to working with a broader approach that takes seriously colonial and imperial histories has implications for the way in which we understand political issues in the present. The political communities of European states extend beyond national boundaries with implications for how we should understand borders as functioning within practices of appropriation and exclusion. Once we acknowledge the broader histories that have shaped us, this has implications for the concepts that we develop on the basis of a proper consideration of those histories.

Epistemological

Epistemological justice, which I argue is central to any reparatory sociology, requires an address of the ways in which colonisation, slavery, and indenture were integral to the project of modernity. Such processes structured knowledge claims within theories of development and ‘progress’ as well as its institutions, such as universities, but were rendered invisible in representations of its ‘civilizational’ project.

Epistemological justice, then, involves recognition of the knowledge claims of others in terms both of respect and (re)constructive response; whether in terms of disagreement or agreement. A central aspect of this would be an ethical practice of scholarship that acknowledges the work that has already gone on by those whose activism has forced our attention, as well as engaging productively with critiques and contestations around their implications for contemporary politics, including the politics of knowledge production.

As I argued in the inaugural issue of the Global Social Challenges Journal, a reparatory sociology requires both the repair of the social sciences as well as being invested in the collective address of the inequalities legitimated by standard social science. Recognising the modern world as the colonial global world enables us more adequately to contextualize events and processes that are often presented as separate and to understand them within a connected frame of reference – one committed to repair and transformation, and a world that works for us all.

If you enjoyed reading this post, you may also be interested in Gurminder K Bhambra’s recent book, Rethinking Modernity: Postcolonialism and the Sociological Imagination; Connected Sociologies; and, with John Holmwood, a video lecture series on Colonialism and Modern Social Theory.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

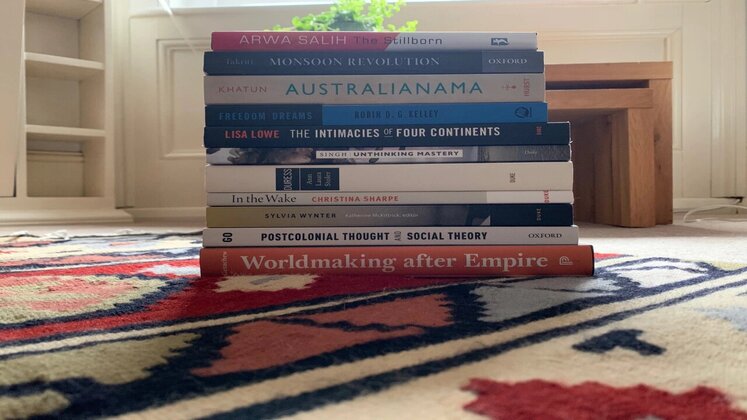

Image Credit: Adapted from Tony Hand via Unsplash.

While we engage rightly, in recognizing the inequalities of women, indigenous, persons of colour, LGBTQ+, and those with special needs, we are in danger of being ‘nice’. True change will occur with our own thinking when we understand the sociological history of ‘modernity’ based on European empire leaving a legacy of diminishing the contributions of the human population on the earth before ‘recorded’ history. Encourage all who strive for social justice to re-discover by re-thinking modernity, yes it is a re-thinking NOT an additive to existing understanding of modernity. Salute Gurminder efforts to raise social justice in this way. We must understand colonial collaboration with missionaries who have left quite a legacy throughout the world.

I do encourage those sincerely advocating for social justice out of concern for the earth’s environment and disparity of experiences (of women, indigenous, persons of colour, LGBTQ+, special needs, and whose household income is below the poverty line) will strive to rethink modernity. To re-think our colonial (mired with missionary collaboration) past is essential in our being able to accept the contributions of humanity the world over, not just from one continent Europe.

I have two objections against this proposal. First, it is factually outdated. Already more than half a century ago, claims about a non-modern world that would be qualitatively different from the modern world and that would be in a superior position vis-à-vis the non-modern world were criticised and deconstructed effectively by scholars like Andre Gunder Frank and other scholars promoting dependency theory. Since then, such outdated claims have disappeared from mainstream sociology, so what is the need for paying attention to such fossile views again? There are journals enough to highlight the interwovenness of the world, so what is new here?

Second, the problem with oxymoron terms like epistemological justice and reparatory sociology is that they impose an ideological instead of academic frame of reference on our work as sociologists. It leads to a situation in which such ideological criteria come to shape decisions about which research will be funded and published in journals and which not. I write this based on decades of doing research that tries to disentangle the factors and mechanisms of phenomena that clearly represent a violation of justice, like ethnic violence and discrimination. The latter is my motivation to do such research. However, such motivations themselves are useless as guidelines for doing the sociologcal work itself. Such work can only be fruitful if guided by sociological instead of ideological standards.

Extreme right parties and voices do not have a monopoly of threatening academia and sociology with ideological cleansing. Academic freedom and responsibility are at stake here. The best way to do justice is to do sociology according to its own standards instead of standards that are alien to it.