Discussing recent trends in European science diplomacy, Kapil Patil and Maria Rentetzi argue that the post-Cold War consensus of high-level co-operation is giving way to more fractured and politicised model grounded in geo-political competition.

The war in Ukraine is causing a fundamental rethink in Europe’s post-Cold War attempts to build a mutually interdependent global science system. Specifically, the contradiction of the European scientific community’s expectations about Moscow’s willingness to put global governance above regional concerns is ushering in a so-called “post-naïve” age of scientific collaborations that is shaped by both European values and transatlantic security interests. Already, scientific collaborations – long heralded as a tool for building trust – have been turned into an instrument of political coercion. Since the outbreak of conflict, western countries have been relentlessly imposing stricter sanctions on Russian science, with the United States becoming the latest to join many European countries in ending scientific ties with the Russian state research and scientific bodies.

The White House release of June 11 emphatically stated that the United States would “wind down institutional, administrative, funding, and personnel relationships and research collaborations in the fields of science and technology with Russian government-affiliated research institutions.” The Communiqué of the G7 Science Ministers’ meet held on 12-14 June 2022 also reiterated the Western alliance’s stance of “restricting as appropriate, government-funded research projects and programs involving Russian government participation.”

Western science diplomacy now aims to dissociate individual scientists from the Russian state institutions and reinforce their freedom of research and speech.

While there is skepticism around the ability of sanctions to crimp the Kremlin’s war machine, the deepening scientific restrictions are also shrinking the space for science diplomacy to provide any meaningful communication channel between Europe and Russia. With an increased enmeshing of scientific collaborations in the ongoing geostrategic contest, the focus of western science diplomacy has turned to individual Russian scientists and researchers facing “persecution” in their homeland. The war in Ukraine has divided the Russian scientific community over its support for Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. Since the outbreak of hostilities, over five thousand Russian scientists have publicly criticised the Kremlin’s decision to invade Ukraine and appealed for an immediate cessation of war.

Western science diplomacy now aims to dissociate individual scientists from the Russian state institutions and reinforce their freedom of research and speech. To this end, leading European research bodies such as the DAAD and European Research Council (ERC) have announced support to dissenting Russian scientists through engaging them in various joint research activities. The ERC scientific council’s statement resolved to firmly stand behind “courageous Russian scientists who have spoken out against this war.” With leading European research bodies and institutions suspending cooperation with Russian state entities, various intermediate and bottom-level science actors now carry the onus to rebuild the broken scientific partnerships.

They mainly include civil society organizations and individual grantees using their personal contacts to foster dialogue and cooperation through informal and track-two modes of engagement. The track-two framework mostly features individual scientists and researchers speaking to each other to explore avenues for renewed scientific arrangements and normalising political ties. Traditionally, the ERC projects and schemes have presented a crucial bottom-up platform for researchers to forge innovative scientific collaborations and build trust and intercultural understanding. Although, the war in Ukraine has affected the regular exchanges between scientists, the longstanding ties offer a virtual channel to rebuild dialogue, given the scientific communities’ inherent personal and professional obligations.

On the one hand, European science diplomacy thus tries to leverage this limited space available to individual scientists for collaboration, including activities like evaluations and peer reviews. Such smaller initiatives often prove to be of great significance, as seen from the past experiences. During the Cold war, for instance, scientists across the Berlin Wall quietly worked together on novel scientific projects, laying the ground for furthering political cooperation that, in turn, facilitated movement towards détente. The scientific ties also enabled the two sides to embark on projects like the Apollo-Soyuz mission, which became a symbol of goodwill amidst a deep-seated ideological contest.

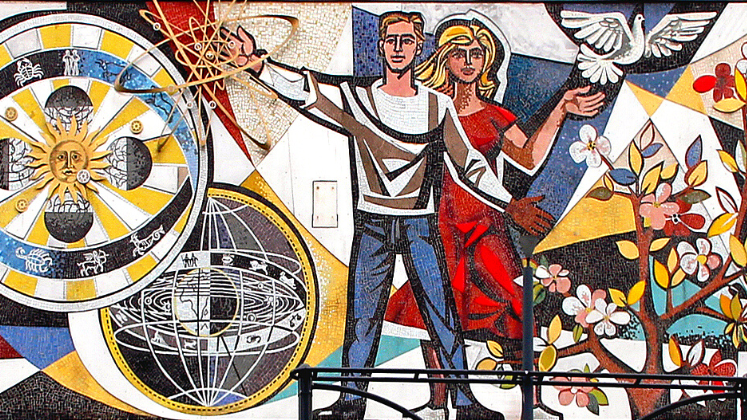

Image Credit: Florian Schäffer, Detail of Fritz Eisel, Der Mensch bezwingt den Kosmos, via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

Image Credit: Florian Schäffer, Detail of Fritz Eisel, Der Mensch bezwingt den Kosmos, via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).

On the other hand, the Ukraine War presents a much different context from the science diplomacy of yesteryear. Scientific cooperation during peacetime offers no guarantee to secure long-term cooperation and peace among eternally competing states engaged in maximising their relative gains. It is essential to underline that several Russian scientists and state institutions support Putin’s ongoing war and the capture of Ukraine’s territories. The EU’s science diplomacy, therefore, can no longer presume the scientific values of “rationality”, “transparency”, and “universality” as given. Instead, scientific collaborations have increasingly becoming a “diplomatic activity” balancing many interests, risks, values, principles, and regional concerns, as outlined in the recently published DAAD foreign research policy perspective. History, however, teaches us that this has always been the case, especially during Cold War.

The Ukraine war is thus pushing scientific collaborations more deeply into the calculus of security and inter-state relations.

The multilateral scientific entities, such as the CERN, IAEA ICTP, and various big science facilities across Europe, too have been forthright in condemning Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. These institutions have been the vanguard of science diplomacy through their multilateral scientific projects. Although Russian scientists continue to participate in the activities of these institutions, CERN has decided to terminate the cooperation agreement with Russia and Belarus after its expiry in 2024. The IAEA board of governors, too, have deplored Russia’s invasion, with only two votes against the resolution. The Ukraine war is thus pushing scientific collaborations more deeply into the calculus of security and inter-state relations.

Consequently, scientific collaborations post-Ukraine will likely see negotiations over concurrent strategic interests of the competing states. Furthermore, the rising authoritarianism globally also forces western scientific bodies to become more circumspect in opening their scientific systems to foreign partners like China, which is often accused of denying reciprocal access to its markets and scientific personnel. The growing entanglement between foreign and security policies marks a setback to Europe’s scientific internationalism, especially when the world routinely faces planetary challenges of the Anthropocene, like a pandemic, climate change, and global slowdowns.

Settling the contestations around the “European” order as a way forward to rebuilding cooperation around various common challenges is certainly easier said than done. With Ukraine war showing no end in sight, science diplomacy, with its changing rationale and shrinking space, has only diminishing returns to offer in furthering global cooperation. If one thing seems clear in recent pronouncements from Europe’s scientific world, the phase of much talked about post-Cold War science diplomacy may well be behind us.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Florian Schäffer, Detail of Fritz Eisel, Der Mensch bezwingt den Kosmos, via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0).