There is often an assumption in evidence based policy, that evidence means the findings of quantitative studies or randomised control trials. However, in practice evidence is often understood differently. Drawing on a study of Welsh policy actors, Eleanor MacKillop and James Downe highlight four different approaches to evidence in policymaking and suggest how researchers and policy organisations might use these findings to engage differently with policy.

The Covid-19 pandemic saw the refrain of ‘following the evidence’ become a commonplace. But, what is meant by evidence can vary according to who is asked, the context, as well as many other factors. These perceptions are especially important when it comes to one group, policymakers, because, it directly effects why evidence is used, or not, and ultimately how policy is formulated.

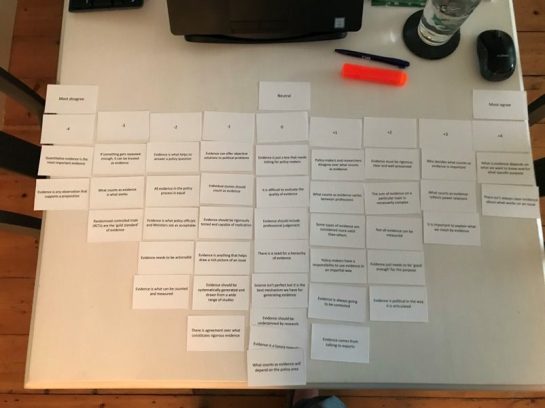

To explore these understandings of evidence, we conducted research to analyse the perceptions of Welsh policy actors. We used a method developed in psychology – Q methodology – to study people’s attitudes and perceptions regarding what evidence means. Our participants ranked a set of statements collected from the existing literature, newspapers, and expert interviews on what evidence means into an agree-disagree pyramid shape. As shown below, they could only most agree with two statements (+4 column on the right of the picture) and most disagree with two statements (-4 on the left).

Fig.1 Example of Q Grid

We conducted interviews with 34 participants from across the Welsh policy community, from Ministers to civil servants, Senedd members and staff, civil society organisations, and academics.

Four evidence profiles

It turns out there are broadly four profiles of perceptions and attitudes towards evidence in policy making in Wales, which we called: Evidence-Based Policy Making (EBPM) Idealists, Political, Pragmatist, and Inclusive.

EBPM Idealists

These respondents believe that evidence ought to be rigorous, clear, and well-presented (ranked +4) and that policy-makers have a responsibility to use evidence in an impartial way (+4). For these respondents, evidence could be likened to truth and facts:

“As officials our job is to tell the truth. You must always give an honest representation of the facts.”

These respondents were not, however, fully wedded to the principles of EBPM, for instance making it clear that RCTs (Randomised Control Trials) “are useful but I don’t think that they are the gold standard”. For them, general ideas of EBPM needed to be interpreted within the real world of policy.

Political

These respondents believe that what counts as evidence is influenced by politics. They ranked the statements: ‘evidence is political in the way it is articulated’ (+2), and ‘evidence reflects power relations’ (+2) higher than any other of the profiles.

The Political respondents didn’t deny all aspects of EBPM. For instance, one participant explained how they agreed that policymakers have a responsibility to use evidence in an impartial way, but recognised that they serve political masters.

“The kind of evidence that they [i.e., ministers] value might be different from party to party […] We can’t be completely impartial”.

Pragmatists

These respondents believe that the answer to ‘what counts as evidence’ will vary according to the different factors involved in a particular context. This transpires through the two statements that they most agreed with: ‘not all evidence can be measured’ (+4) and ‘what counts as evidence varies between professions’ (+4).

Pragmatists illustrate the difficulty of working with evidence, with the evaluation of the quality of the evidence being difficult (+3) and how not all evidence can be measured (+4). One quote epitomises this profile:

“Having been in the policy process and received various sources of evidence, I don’t think I have ever felt that I can deduce a course of action easily from the evidence. There is always judgement involved.”

Inclusive

This profile includes participants who believe that what counts as evidence should be as broad and open as possible, with ‘evidence [being] anything that helps draw a rich picture of an issue’ (+4) and ‘evidence being what helps to answer a policy question’ (+3) all being ranked higher than in any other profile. One respondent illustrates this viewpoint:

“I was a policymaker for forty years so anything that will give you that rich picture of a policy area is very useful evidence, regardless of how it is obtained.”

This profile stressed “the need for a broad spectrum of evidence, the need for different methods to get a full picture.” Overall, this profile emphasised the need for evidence to include a wide arsenal of tools, methods, and elements.

Shifting profiles

Our respondents’ views of evidence were contextual, nuanced and variable. However, there were areas of agreement across all four profiles. For example, all agreed that it was important to explain what we mean by evidence and each profile disagreed that ‘evidence is a luxury nowadays’, which suggests the need for more discussion on what counts as evidence and the role it plays in policy-making.

The EBPM Idealists included the greatest number of higher degree qualifications. This could suggest a correlation between length of time spent in academic training and a stronger belief in EBPM ideas (at least in this study). Contrastingly, when comparing length of service across profiles, the Inclusive (15 years) and the Pragmatist (11 years) profiles included the longest time spent working compared with the Political and EBPM Idealist (8 years) profiles. This may mean that the longer time one spends dealing with evidence questions in the ‘real world’, the more inclined you will be to have a varied and contextual understanding of evidence.

Our research aimed to improve understanding of what evidence means to different policy actors in Wales. It shows how similar behaviours towards evidence may be garnered in different organisations, whilst opposite viewpoints – e.g., EBPM idealists versus Political – can cohabitate in the same organisation – e.g., the Welsh Government.

The EBPM Idealists include the most respondents, but they don’t dominate. This emphasises how varied policy actors’ attitudes towards evidence are. We also found that all participants agreed that their understanding of evidence had changed over time.

What are the lessons from this research? For organisations involved in policy, it is important to recognise that different actors have different perceptions of evidence, and they could use our findings to think about how different meanings of evidence may impact their work. Evidence providers (such as researchers and academics) need to understand whether and how policy actors may be open to evidence, whether for example they are EBPM Idealists who will only heed certain forms of evidence or Pragmatists, who are working in a context and on an issue which they see as amenable to evidence. These processes ultimately also require brokering skills and knowledge.

This post is based on the authors’ paper, What counts as evidence for policy? An analysis of policy actors’ perceptions, published in Public Administration Review.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: LSE Impact Blog via Canva.

Framing policies at national level or at local level call for a different set of evidences. Since framing policies is always contextual. It’s good to develop a policy framework yet Covid-19 is now a universal issue which is multidimensional including political. The core issue, especially in developing nations, remain acceptability of vaccination among various societies for political and cultural reasons. I think researchers can also focus on research to address how to overcome these contextual biases when framing policies for these countries. It’s important because so many people lost their lives for having an inherent biases about vaccines and medicines prepared by various multinational companies belonging to various countries that blame each other for spread of virus. Regards

Insightful analysis on @LSEImpactBlog about the perception of evidence in public policy. The diversity of approaches (EBPM Idealists, Political, Pragmatist, Inclusive) highlights the complexity and nuance needed in decision-making. Key for a more informed and nuanced political debate.