Drawing on his study of recent developments in Mexican science policy, Luis Reyes-Galindo, discusses how common concepts from social science have been weaponised to the expense of academic freedom.

Epistemic justice, decolonising the curriculum, ontological diversity, the democratisation of science and knowledge co-production are influential concepts across the humanities and social sciences. At heart, these are calls for plurality and diversity in global knowledge production criticising the idea that science – more generally, the West – produces superior knowledge, over that of any other culture.

The superiority of institutionalised scientific knowledge in every situation can be destabilised by real world examples, including many in my own research field, Science and Technology Studies (STS): traditional agricultural communities can have better technical knowledge about food security and crop adaptation to local consumption needs than plant scientists; laypersons can produce knowledge about environmental disasters that legitimately challenge scientific expertise; indigenous communities better understand human relationships to ecosystems, breaking with the logic of conservation scientists. Ignoring these knowledges solely because they are not from institutionally recognised scientists creates obvious cases in favour of epistemic protection policies.

We also know that scientific institutions can and have, at times, permitted social injustices. A recent Nature editorial, echoing research that shows the ties between contemporary biology, racism, and eugenics, confronted how racist thinking was published and thus sanctioned by Nature itself. In a nod to the social sciences, the editors also denounced as false “that Europe’s knowledge was (or is) superior to that of all others, and that non-European cultures contributed little or nothing to the scientific and scholarly record.” This is no social science harangue, but an editorial in a leading outlet for highly institutionalised natural science.

In 2018, these concepts made an unusual appearance in Mexican science policy. The incoming Morena party, having recently swept national elections, proposed wide-ranging reforms to the national framework on science, technology and innovation, using new ‘values’ to drive science. These included

“epistemological rigour, equality and non-discrimination, inclusion, plurality and epistemic equity, diálogo de saberes, the horizontal production of knowledge, collaborative work, solidarity, social good, and precaution.”

Some were hopeful that having geneticist María Elena Álvarez-Buylla, a natural scientist concerned with social issues, as head of Conacyt (Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología) would lead Mexican science out of its constant state of precarity, and to also responsibly deal with pressing problems in, for example, bio- and agrotechnology policy. Others, more acquainted with the incoming director’s animosity towards any science that was unaligned with her own political views, were not so sure.

In 2018 I began documenting reactions to these reforms. Across the federal government, instructions from populist party figurehead President Lopez Obrador were clear: dismantle the power structures of the old regime and replace them with Morena’s. There was a political drive to eliminate all but the core funding channels for science and technology, including for public research institutions, outside of the State’s immediate control. Because of Conacyt’s ‘anti-neoliberal’ agenda, the private sector was totally excluded from science policy. Following the contrarian populist playbook, politically unaligned scientists became increasingly portrayed by the President in his daily televised speeches as perverted by the interests of ‘conservatism,’ ‘neoliberalism,’ and ‘corruption.’

Social scientists unacquainted with Mexican politics might be thrilled to read these apparently progressive statements in a national law. My record of the Mexican scientific and academic community, however, have shown that reactions were negative across the board within the natural sciences, and in academia at large. Once examined in detail, these reforms made no use of the ‘new values,’ instead reordering the Mexican scientific system to centralise decision-making into the federal government’s hands. It also proposed funding be assigned following a ‘State Agenda’ that was built without input from the scientific community, and with ultimate policy decision-making power in the hands of the President, advised by a privy council of party and military allies.

These ‘values’ are the spearhead of a ‘trickle down’ populist science governance, which parrots strongarm tactics used by the federal government across the entire political landscape, including the militarization of the national police forces, and unrelenting attacks against civil society and government-critical journalism (admittedly, of varying quality). Conacyt has been a central actor in many of these controversies: despite protests from indigenous communities, social scientists, and environmental experts knowledgeable about the Sureste region Conacyt has persistently supported the deeply controversial Tren Maya project. Damning impact studies funded by Conacyt itself ‘disappeared’ from the public record. These, contradictorily, are examples of the so-called testimonial and hermeneutical injustices Miranda Fricker named when she coined the term ‘epistemic injustice.’

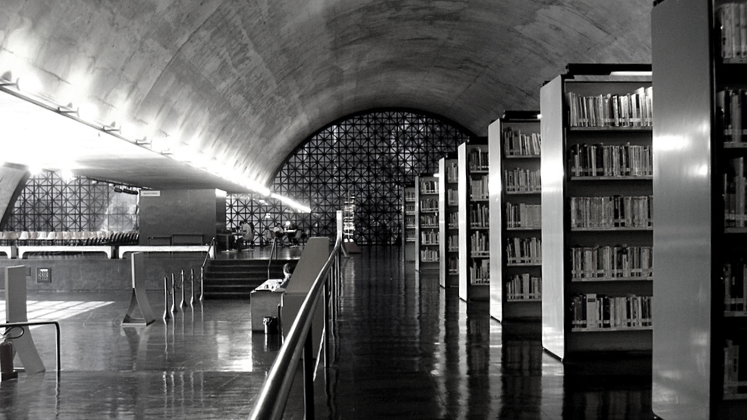

Image Credit: Detail and colour adjusted from verifex, UNAM (National Autonomous University of Mexico) 11, via Flickr, (CC BY NC 2.0).

Image Credit: Detail and colour adjusted from verifex, UNAM (National Autonomous University of Mexico) 11, via Flickr, (CC BY NC 2.0).

Just as worrying, cronyism at the highest levels of Mexican politics has bypassed academic cultures and basic scientific ethics. A series of public scandals – awarding the highest academic merit to an unabashed plagiarist, Mexico’s Attorney General Alejandro Gertz Manero; nominating for the Supreme Court presidency a minister who was publicly denounced to have plagiarized both the totality of her undergraduate and a good chunk of her doctoral dissertations – have evidenced how Conacyt’s director and the federal government feel comfortable ignoring baseline academic standards to favour their own.

As with many governments in the ‘populist’ vein, Conacyt has chosen a path in which political necessity trumps basic ethics and truth. As in recent cases of ‘post truth’ in the Global North, López Obrador and Conacyt’s concerted attacks on science have weaponised academic concepts taken as common-sense in the social sciences. ‘Populism,’ as recent Latin American scholarship has shown, is not necessarily anti-democratic or destructive. Yet, in the Mexican case, it is clear that despite sugar-coating it in epistemic justice discourse, institutional violence against academic cultures is an ongoing course of action for the current administration. In many ways, despite its alleged Leftist discourse, López Obrador’s transgressive populist version of scientific governance is more aligned with that of a figure like Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro than with other important figures in Latin American populisms and its Lefts, like those of Lula da Silva or Gabriel Boric.

This post draws on the author’s article, Values and vendettas: Populist science governance in Mexico, published in Social Studies of Science. For more research on STS and science governance issues in Latin America, have a look at the journal Tapuya: Latin American Science, Technology and Society.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Detail and colour adjusted from verifex, UNAM (National Autonomous University of Mexico) 11, via Flickr, (CC BY NC 2.0).