Since its purchase by Elon Musk last year, Twitter has undergone a series of rapid changes, largely with an eye to making the platform profitable. Considering these developments and those on other platforms, Mark Carrigan, suggests that just as academic social media has become relatively mainstream the dynamics underpinning academic engagement on social media have fundamentally shifted towards a pay to play model.

It has been less than six months since Elon Musk bought Twitter. In this time the platform has changed in all manner of ways. The workforce has been slashed. The reliability of the service has declined precipitously. The accounts of unreconstructed trolls have been reinstated. The interface has been continually tweaked in the hope of improving engagement. There has been a startling upsurge in spam, particularly through direct messages. The most significant shift however is the introduction of a subscription tier, Twitter Blue, which offers a blue tick for anyone willing to pay a monthly fee. The reasons why someone might pay for this include the perceived authority of a blue check mark, access to the two-step authentication that has now been withdrawn for ordinary users and a desire to support a platform that many users have been logging into daily for years.

The most significant reason though is the obvious shift towards a paid visibility model of social media, in which only those willing to pay the monthly tribute have the opportunity to be seen and heard. The movement in this direction from Musk’s Twitter has been slow but significant. The initial promise was that tweets from verified users would get ‘prioritised’ rankings in search, replies and mentions. Introducing tweet level metrics in the view count, was clearly intended to nudge users in the direction of seeking this prioritisation. It meant users who would not have been inclined to explore the specialised metrics section of the interface (interesting to aspiring influencers and those managing organisational accounts), were encouraged to consider the relationship between views and engagement. Even the placement of the metric in the interface inclines the user towards reflecting on the relationship between views and the familiar trio of replies, retweets and favourites now adjacent to it. If your replies, retweets and favourites don’t live up to expectations then perhaps you might want to do something about your views?

It was announced recently that only subscribers will be included in the ‘For You’ stream from this point onwards (though this was soon partially rolled back). The carrot of prioritisation has become the stick of exclusion. Further, it was recently revealed that a small cadre of Twitter VIPs are being manually signal boosted, not least of all Musk himself, who reportedly demanded amplification after a tweet he sent during the super bowl failed to achieve the same level of visibility as a tweet by Joe Biden. It remains to be seen what inducement Musk’s Twitter will turn to next to encourage the majority of users to relent on their resistance to subscription. However, it is likely we will see a gradual disintegration of the user experience for non-subscribers alongside a deterioration of the platform as a whole, as a skeleton staff struggling to keep the service running in the manner users had become accustomed to. The fact Twitter’s social influence has always vastly exceeded its user base makes the problem even worse, because the preponderance of politicians, celebrities and business leaders who use it make it an obvious target for hackers and intelligent services.

It is tempting to explain these changes purely in terms of the figure of Elon Musk. While it has been a gripping spectacle to watch a once lauded billionaire burn $20 billion in a bonfire of hubris, the trajectory of Twitter illustrates a broader change underway in the landscape of social media. Platforms like Facebook (2004), YouTube (2005) and Twitter (2006) are rapidly approaching their twentieth anniversaries in a markedly different economic climate to the one they emerged in. These firms grew amidst the wreckage of the dot-com crash in the early 2000s, framing themselves as ‘Web 2.0’ to differentiate them from their failed predecessors. They enjoyed a low interest rate environment, conducive to their growth, in which anticipated future returns took precedence over present day results. Now the expected post-pandemic hegemony of big tech hasn’t materialised, these firms confront a high interest rate environment with declining consumer spending. This is the most hostile economic environment they have faced and recent changes at Twitter illustrate the challenges involved in finding a sustainable business model.

In short, the limits of the advertising model have been hit. Facebook and Instagram recently announced Meta Verified, which also includes algorithm boosts for subscribers. These subscription models build on the long, slow decline of organic reach on social media in order to nudge people into paid advertising. This could be seen for example in Twitter’s normalisation of ‘promoting’ tweets tempting ordinary users who might be put off by the language of advertising to nonetheless consider paying for one off signal boosts. The problem is that it is ‘organic reach’, the capacity to be seen and heard without paying that drew many people to social media in the first place. The promise of participatory media was that we could have our say in this new public sphere. We are now being told “Thank you for using Web 2.0. Your free-trial period has ended!” as the media commentator Charlie Warzel recently put it, at precisely the moment when these platforms have become part of the institutional landscape rather than disruptive novelties.

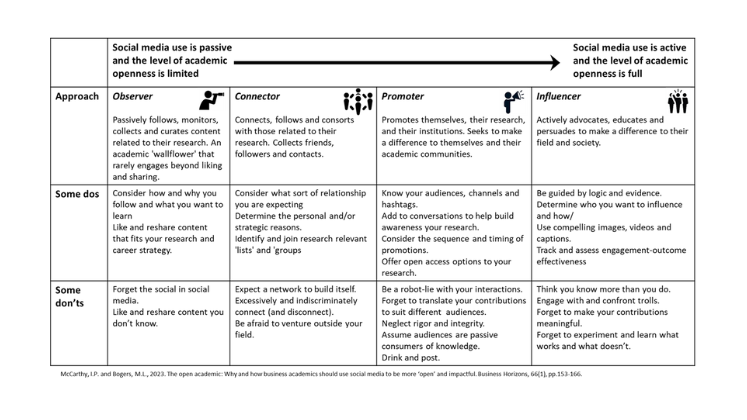

Unfortunately, after years in which social media for academics was regarded as oxymoronic, we are now encouraged by universities and funders to embrace social media with enthusiasm. I’ve done more than most in encouraging this trend as a researcher, author and trainer, but it’s one which increasingly worries me given the broader shift we are seeing. The content of this encouragement tends to repeat motifs such as “get your work out there”, “publicise your research” and “make an impact”, which are becoming increasingly misleading with each passing year. These ambitions are not in any way impossible but achieving them in a sustainable way is becoming more demanding, with greater risks that are yet to be adequately handled within universities. It feels the professional normalisation of social media has reached its crescendo at precisely the point where the risk/return ratio no longer makes sense for many academics. Social media has changed and the guidance universities offer academics urgently needs to catch up with this new reality.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Adapted from Alexander Shatov via Unsplash.

5 Comments