Open science is increasingly becoming a policy focus and paradigm for all scientific research. Ismael Rafols, Ingeborg Meijer and Jordi Molas-Gallart argue that attempts to monitor the transition to open science should be informed by the values underpinning this change, rather than discrete indicators of open science practices.

Following a flurry of policies and investments in Open Science (OS), there are currently a wave of efforts to monitor the expected progress: OS monitors at the European and national levels (see France and Finland), a monitor of the European Open Science Cloud, and various European Commission projects, for example looking into indicators for research assessment (Opus) and impacts of OS (PathOS). UNESCO is also striving to monitor the implementation of its OS Recommendation, which includes an explicit commitment to the values and principles for science to be a global public good.

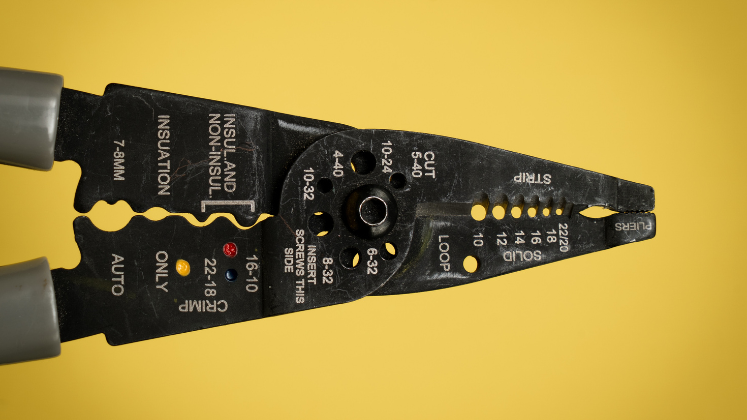

Yet monitoring Open Science is proving difficult. OS is an umbrella term (or as some say a mushroom!) referring to a diverse constellation of practices and expectations, from open access (OA) publishing, to citizen engagement (see Fig. 1). A quick look at policy documents reveals striking diversity and ambiguity in the focus and scope of OS initiatives. Different stakeholders emphasise different goals: increasing accessibility or efficiency, fostering flows across academic silos, engaging non-academics, democratising science within and across countries… this multiplicity of activities and ambivalence of goals, makes monitoring extremely complex.

Fig.1: A mushroom illustrating the diversity of activities included within Open Science. Source: OpenAire (based on Eva Méndez).

We argue efforts to monitor open science should focus on shedding light on which and how the various strands of open science are making progress and what their respective effects and impacts are. In other words, we shouldn’t monitor whether there is more or less open science, but what types of OS are developed and adopted, by whom, and with what consequences. This means monitoring should include not just the diversity of OS channels (the supply side), but also the multiplicity of usages and outcomes (the demand side).

we shouldn’t monitor whether there is more or less open science, but what types of OS are developed and adopted, by whom, and with what consequences.

To achieve this requires a focus on open science ‘trajectories’. Similar to how monitoring the ‘colours’ of open access aids understanding of both OA development and who benefits from it, it is essential to understand the trajectory of both OS in practice and whether it is making, or not making, science more equitable and responsive to global needs. For example the way in which some open access investments in rich countries, such as transformative publishing agreements, may result in less equitable outcomes in access to publishing services for other countries. More open science does not always lead to better outcomes.

New models of science require new monitoring frameworks

Monitoring and evaluation frameworks draw on theoretical models of how science and science policy works. After the WWII the so-called ‘linear model’ assumed that science contributed to human development by supporting technology and thus innovation. Since this model assumed a linear relationship, it was monitored by input-output indicators, as illustrated in the OECD Frascati Manual.

In the 1980s, it became apparent that countries like Japan succeeded at innovation without having the largest or best scientific inputs. Innovation was achieved through fluid interactions of companies with researchers and other stakeholders. This led to the development of the policy model of ‘innovation systems’ and its associated monitoring frameworks, for example the OECD’s Oslo Manual or the European Innovation Scoreboard.

In the last 30 years we have witnessed how more innovation does not always lead to increases in well-being.

In the last 30 years we have witnessed how more innovation does not always lead to increases in well-being. While many innovations have improved people’s livelihoods, other innovations have led to negative consequences. This new understanding of science gave birth to a third science policy model, known as transformative innovation policies. According to this model, science policies should aim to direct research and innovation towards ‘good ends’, as described for example by the sustainable development goals (SDGs). As a result, a new generation of evaluation frameworks is being developed.

The principles of these new monitoring efforts can be useful for thinking how to monitor open science. Under conditions of high uncertainty, epistemic diversity and pluralism which are characteristic of transformative innovation policies, three strategies are highlighted:

- Learning: fostering reflection and self-assessments as transformation of science unfolds.

- Directionality: mapping the trajectories or directions pursued across the various dimensions observed

- Outcomes: focusing on effects and outcomes in the beneficiaries of initiatives, in addition to the more traditional monitoring of outputs (science supply).

Monitoring open science as a systemic transformation: learning, directionally and outcomes

Science is currently undergoing a transformation that is driven in part by the revolution in communication technologies and artificial intelligence, in part by a more fluid and more problematic interaction between science and society. This is a response to the contribution of science to harmful innovations and a willingness to redirect research towards well-being and sustainable development goals.

This transformation has led to policy developments such as Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI), research integrity, public engagement, evaluation reform and research for SDGs – which overlap with OS. We can think of this constellation as part of the last (third) science policy model, which aims to transform research systems in order to respond to societal demands and needs.

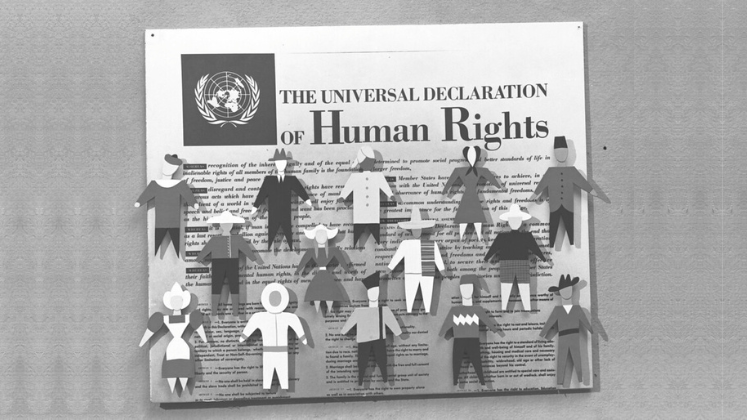

If open science is understood as not just an optimisation by improving information flows, but as part of a wider transformation, comparable to how scientific journals changed the social and technological basis of science in the 17th century, then it would be wise to adopt a monitoring framework that captures various aspects of the change. Monitoring should therefore include the effects and broader social implications, especially those relevant to the values and principles as expressed in the UNESCO OS Recommendation (Fig.2).

Fig.2: The values and principles of Open Science according to the UNESCO Recommendation. Source: UNESCO (2021).

Let us apply three insights from transformative innovation evaluation to OS monitoring.

Learning: Monitoring should be designed with a formative framework that supports learning and strategic decision-making – ‘opening-up’ in terms of policy options. This means that it should not concentrate on a few ‘Key Performance Indicators’, as is the case in monitoring programmes with narrowly defined dimensions of success. Instead, it should be pluralistic, embracing multiple dimensions and be flexible for its application in a variety of contexts.

Directionality: Monitoring should capture the trajectories of open science within and across the dimensions considered. This means looking into the various options and the implications for the effects of a given OS activity. For example, some routes to OA (such as gold or hybrid) may have potential implications in terms of equity (excluding some communities from publishing), integrity (effect of APCs in the reviewing process) and collective benefits of science (making some topics with resources more visible). Similarly, in Open Data (OD), both the FAIR and the CARE principles of data are highly relevant, as they have effects on who can use and benefit from the research outcomes.

Outcomes: Given that science is a complex system, policies can lead to unexpected and undesirable outcomes. Therefore, not only the outputs, but also the uses and effects of OS need to be monitored. This means broadening the focus of monitoring from outputs (what is done to support OS) towards activities that tell if OS is making a difference. What are the uses OA publications outside of academia? How is Open Data re-used and by whom? How much participation is there in a given university? How does public engagement influence research agendas in a given field? To answer these questions about usages and effects and usages of OS, we believe that it will be necessary to conduct interviews first and surveys later, following the same path as the OECD in the Oslo Manual and the project SuperMoRRI on indicators for RRI.

Monitoring if open science lives up to its ideals

Open science holds promise as a process of transformation, but the relationship between OS activities and the values it espouses are not inevitable. The promises of modern science have rarely been kept and have instead often led to unanticipated and troubling consequences, from nuclear energy to the internet. The question is not whether there is more or less open science, but what type of open science we are making. Monitoring OS should be aimed at reflective learning if OS activities are to take directions that transform science towards desired outcomes, towards a more inclusive and sustainable future.

This blog is based on a draft paper and presentation in the 2023 Eu-SPRI conference. A special session of the 2023 S&T Indicators Conference will continue this discussion.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: National Cancer Institute via Unsplash.

I am not yet persuaded to label quality and integrity, collective benefit, equity and fairness, and diversity and inclusiveness as values. My current inclination is to call them goals, and posit a hierarchy of goals.

I agree with Gavin insofar, as I think these are partly values humans can have (a researcher being upright or fair) and partly values ascribed to the scientific enterprise as such (science should be equitable or high-quality). However, I think these are not goals either, to me these are “scientific values”, which can be derieved from the human values.

Independently from this point, which I do not see as so central for the post, I really appreciate the focus on pursuing societally valuable goals and monitoring of outcomes. However, I would like to add for consideration that many open science practices are as yet too new to see outcomes or even actual impacts, and that outputs have value in and of themselves to steer open science developments. And, most imporantly, as well as more generally, I would caution against overemphasizing the orientation of science (and thus, open science) towards certain predefined goals. This is a necessary tension, and we need to define goals, but without completely disregarding reasearch not directly aimed at any societal goal.

In that regard, I am also very sceptical that restricting research early on, because it could have some detrimental consequences later, would be a service to humanity, and the examples (nuclear power, internet) are very good examples in point – but this is a fundamental question and also probably to be discussed elsewhere.

Finally! Having listened to the open debate for almost two decades – finally someone has asked the question “but how do you evaluate if open science is successful?” During the COVID-19 pandemic, open science in the form of preprints spawned countless incorrect claims for miracle cures (Ivermectrin) and conspiracy theories. Did this open science help society or hurt it? Science and society would be better served if scientists shared their research data – not just the results of their research – which is why so many funding agencies have started requiring the deposition of research data. Let’s build on the work and strive to meet good goals – but let’s stop publishing research that hasn’t been proven to be true and where data is not shared.