When published, bad data can have long lasting negative impacts on research and the wider world. In this post Rebecca Sear, traces the impact of the national IQ dataset and reflects how its continued use in research highlights the lack of priority given to research integrity.

Would it surprise you that papers are regularly published in the academic literature that promote the idea that people in sub-Saharan Africa have cognitive ability so low that they are, on average, on the verge of intellectual impairment? Not just papers in ‘fringe’ journals, with little credibility, but in journals published by major academic publishers, Elsevier and Springer, and with influential and respected scientists on their editorial boards.

This blog tells the story of the national IQ dataset. This dataset claims to provide data on average cognitive ability in nation-states, yet in reality is scientifically flawed and has been used to explicitly argue for a genetically-determined racial hierarchy of intelligence. This research has not just been confined to academia, but has done real world harm; work using the dataset was cited in the manifesto of the terrorist who murdered 10 people in a racially motivated attack in Buffalo, US in 2022.

The idea of a racial hierarchy of intelligence is not new. It was an important component of the eugenics movement that had widespread support in the early 20th century. Eugenic ideology assumes human populations can be ‘improved’ through selective reproduction: encouraging those with ‘desirable’ traits to have children, while discouraging those with ‘undesirable’ traits from reproducing. Eugenics (ostensibly) fell out of favour during the late 20th century after the atrocities committed by the Nazi regime took eugenics to its ‘logical’ conclusion by murdering ‘undesirables’. However, this decline had started even before the 1940s, as it became increasingly clear that the simplistic assumptions on which eugenics is based did not hold true. Complex human traits and behaviours cannot easily be bred into (or out of) human populations. Eugenics is ideology, not science.

But eugenics never went away. Eugenics is underpinned by the belief that there are ‘hierarchies’ of humans and, in particular, hierarchies of race and class. One popular method eugenicists have used to identify such hierarchies is by measuring ‘intelligence’. Francis Galton – who coined the term ‘eugenics’ and originated the academic study of eugenics at University College London – pioneered the measurement of intelligence, to rank individuals on what he considered a ‘desirable’ trait.

In the 21st century, intelligence tests are still being used in support of eugenic ideology. In 2002, psychologist Richard Lynn published a dataset which he claims provides an average IQ (Intelligence Quotient) for each nation-state worldwide. This national IQ dataset has been widely used by Lynn and many other researchers, in >100 papers published across multiple disciplines including psychology, economics, biology and political science. This is very surprising if you consider that the average national IQ in the dataset for all sub-Saharan African countries combined is 70. A score so low that would imply large proportions of people in Africa have trouble leading ordinary lives without help.

In the 21st century, intelligence tests are still being used in support of eugenic ideology.

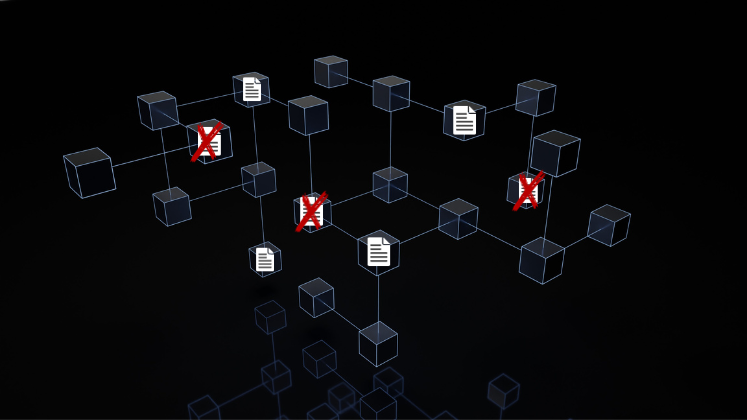

An inspection of Lynn’s dataset reveals why it comes up with such an implausible IQ for sub-Saharan Africa: it is bad science. Lynn calculated national IQs from data on cognitive tests already published in the scientific literature, but these studies largely involve samples that are wholly inappropriate for calculating national averages. Collecting data from a sample which is representative of a national population (in terms of age, sex, socioeconomic position, for example) is difficult and expensive. Lynn’s dataset instead relies on many ‘convenience’ samples, meaning samples which happened to be available: the IQ for Eritrea, for example, is estimated entirely from children living in orphanages. These samples are often very small: the national IQ of Angola is estimated from just 19 people.

The dataset is also systematically biased. No methodology for selecting samples from the published literature into the dataset has ever been provided, though it is clear that selections were made. A review of the literature on cognitive tests in sub-Saharan Africa found evidence for selection bias in that those samples which Lynn included for this region indicated lower cognitive ability than those excluded. Even if it were possible to put all these methodological flaws aside, it is simply not possible to generate a single figure for each nation’s ‘intelligence’ which is comparable worldwide. ‘Culture-fair’ cognitive tests do not exist; all such tests involve cultural assumptions, and will disadvantage people who have experienced little or no formal education.

Many academics have been involved in this exercise of embedding racist and eugenic ideology firmly into the scientific literature

Can the national IQ dataset really be considered science; research produced to help us find out about the world? The deeply flawed nature of the dataset suggests not. Lynn has also used the dataset to explicitly promote eugenic ideology. He claims that cognitive differences between world regions represent genetically-determined differences. He has linked IQ to skin colour, claiming Black populations are less intelligent than White or Asian populations (this is a scientifically meaningless statement given the consensus among geneticists and anthropologists that racial categories do not reflect meaningful genetic differences). And he has written about the policy implications of these differences; arguing, for example, that immigration from ‘low IQ’ regions of the world to ‘high IQ’ regions is problematic, as it will lead to a decline in the ‘quality’ of the latter populations.

There seems little doubt that the primary goal of this dataset is to promote an ideology of a racial hierarchy. Yet this dataset has now been used in dozens of academic publications, lending it scientific legitimacy, and producing research with highly problematic conclusions. Many academics have been involved in this exercise of embedding racist and eugenic ideology firmly into the scientific literature. Authors, reviewers and editors alike have either failed to notice, or were unconcerned about, the dataset’s flawed methods and absurd conclusions about African intelligence. Worse, attempts to keep this unsound work out of the literature consistently fail. Neither the many damning critiques of the dataset which have been published, nor a statement from an academic society circulated to some journal editors, have stopped its continued use.

academic freedom is the freedom to research any question of (social) scientific interest using appropriate standards of methodological rigour. Work which violates such standards should not be given a platform in academia

The continued circulation of the dataset may result from carelessness on the part of researchers, or from their implicit biases, but also from a confusion between academic freedom and freedom of speech. Some academics have made the naïve argument that flawed work should be published in the (social) scientific literature on the grounds of “academic freedom”. But, academic freedom is the freedom to research any question of (social) scientific interest using appropriate standards of methodological rigour. Work which violates such standards should not be given a platform in academia.

Academic structures also do little to incentivise research integrity. Incentives in academia largely favour the acquiring of research funds and publications, on the part of individual scientists, and the acquiring of profit, in the case of the largest academic publishers. Academics need to change these structures by prioritising research integrity in their own work, when reviewing and editing for journals, and when hiring, promoting and evaluating others. Until these structures shift, academia will remain vulnerable to manipulation by actors wishing to misuse science to promote political ideology.

This post draws on the author’s article, Demography and the rise, apparent fall, and resurgence of eugenics, published in Population Studies.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: Brina Blum via Unsplash.

In order to understand better the flaws in regular IQ measurement, please note the work of Ad van de Ven, a researcher who did develop the one and only measurement instrument for cognitive ability that really measures this ability independent of existing knowledge or whateven head-start due to advantageous circumstances etc.

Here is the web site with all the information: https://www.socsci.ru.nl/advdv/

I agree with most of the article but I don’t see how what it says refutes the idea of eugenics.

“Eugenic ideology assumes human populations can be ‘improved’ through selective reproduction: encouraging those with ‘desirable’ traits to have children, while discouraging those with ‘undesirable’ traits from reproducing”. This seems to perfectly agree with evolution, doesn’t it? And it is not in contradiction with “Complex human traits and behaviours cannot easily be bred into (or out of) human populations”. That it is not easy to do, does not mean it is not doable. The more traits one would aim to modify, the more difficult it would be. But it seems totally possible to obtain some results.

If I am not wrong with the above, the bottom line is that such kind of eugenics it is unethical, very much so. This article seems to attempt to say that eugenics is not possible in order to avoid people trying to attempt it. Murdering is unethical but no one attempts to convince anyone that it is impossible in order to prevent murder. Not being accurate makes it easy for those who follow the “Eugenics ideology” to just dismiss texts like this.

And being accurate, showing that any meaningful eugenics would be very difficult, is probably much more effective in making anyone back down from this ideology. Who would pay a high price for a mediocre result?

The primary criticism here appears to be directed to the flawed dataset used, the unstated implications being that flawed datasets lead to erroneous results and therefore only a perfect dataset can produce meaningful results. Is that true, and if so, what would a perfect dataset look like? Because it seems that such a criticism will always exist with every dataset that could possibly be created — either the sample is too small, unrepresentative, or tested using a flawed test. This is true, not just of this study, but any study in the social sciences, and many studies in the physical sciences that attempt to sample random or chaotic phenomena. The proposition that imperfect means meaningless is a fallacy that needs to be dismissed.

“Richard Lynn published a dataset which he claims provides an average IQ (Intelligence Quotient) for each nation-state worldwide.”

Rebecca Sear shows how Lynn’s dataset is flawed: sample size and nonrepresentative sampling. She highlights that the dataset has been used to argue for eugenics. She claims it’s impossible “to generate a single figure for each nation’s ‘intelligence’ which is comparable worldwide.”

I disagree with Penelope Wincett’s comments where she overstates Sear’s case that “only a perfect dataset can produce meaningful results. And where she states, “many studies in the physical sciences that attempt to sample random or chaotic phenomena” are flawed by their very nature.

The physical sciences often have something that the social sciences do not have: the opportunity to run the same samples many, sometimes millions of times. Means, standard deviations, and error bars can describe experimental error. That and replication studies, sadly not enough of these, can help reduce systemic bias.

The issue with most of these “scientific” measures is that they are not scientific at all. I recall taking the IQ Test at school and mention this in my recently published book. Ironically, most people are unaware of the embedded racist/racial measures. This has implications that impact the daily lives of ordinary individuals across the globe. Unfortunately, the eugenics mantra has not gone away but has in fact seeped into every aspect of the human experience. Connect the dots and see.