In Nudging, Riccardo Viale explores the evolution of nudging (behavioural mechanisms to encourage people to make certain choices) and proposes new approaches that would empower rather than paternalise citizens. In Daniele Sudsataya’s view, the book is an insightful and notable re-evaluation of familiar behavioural economic ideologies.

This blogpost originally appeared on LSE Review of Books. If you would like to contribute to the series, please contact the managing editor at lsereviewofbooks@lse.ac.uk.

Nudging. Riccardo Viale. The MIT Press. 2022.

Nudging. Riccardo Viale. The MIT Press. 2022.

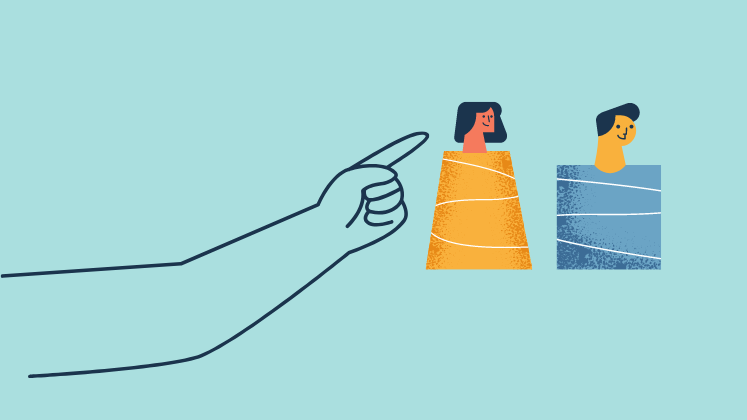

“Five years after surgery, 90 percent of patients are alive” versus “Five years after surgery, 10 percent of patients died”. This is an example of the framing effect, a type of nudge that suggests an individual’s decision-making can be influenced by the way information is framed and communicated. As explained by Gerd Gigerenzer, if a patient heard the former, positively framed statement, they would typically interpret it as a recommendation for the surgery, while hearing the latter, more negative frame may discourage them. We encounter a myriad of such nudges in our daily lives which attempt to influence us into making certain choices without eliminating our free will. For example, a Danish study found that placing more vegetables near the checkout desks in supermarkets led to an increase in vegetable sales. Nudges can thus push us towards making healthy choices, just as easily as they can push us into making unhealthy choices.

This raises the issue: how do we distinguish beneficial nudges from those that are hazardous to our independent decision-making, and can we empower individuals to make choices in their best interest by themselves? This is one of the central topics explored in Riccardo Viale’s book Nudging.

How do we distinguish beneficial nudges from those that are hazardous to our independent decision-making, and can we empower individuals to make choices in their best interest by themselves?

Historically, behavioural economics and their application in different fields would often be neglected in favour of more classically accepted views, such as those in economics. Traditional approaches to economics have viewed individuals as entirely rational beings (Adam Smith’s homo economicus), and as a result treated human affairs through a simple utility-driven lens. However, even among economists, it is now understood that the individual decision-making of humans is susceptible to different cognitive biases, and that one does not always choose the utility-centric option for themselves. This is where the concept of libertarian paternalism comes in, suggesting that certain “correct” choices should be promoted, and that the choice architecture design should be a part of this process, making use of the knowledge gained from cognitive psychology, sociology, and evolutionary social science.

Rebonato defines libertarian paternalism (the ideological framework supporting nudges) as a “set of interventions aimed at overcoming people’s stable cognitive biases by exploiting them in such a way as to steer their decisions towards the choices they themselves would make if they were rational”. The assumption here is that individuals fall prey to biases and self-control limitations, hence nudge interventions steer the weak slightly towards the decisions they would make for themselves if they had complete knowledge, unlimited cognitive ability, and strong willpower, as explained by Thaler and Sunstein.

Nudging is the primary intervention used to put libertarian paternalism into action, as it is grounded in Daniel Kahneman’s theory that human mental activity functions more on System 1 (automatic thinking) than System 2 (logical thinking). This idea was subsequently expanded on by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein in their groundbreaking 2008 book Nudge which made behavioural economics mainstream, and in doing so bridged the gap between cognitive sciences and traditional fields such as economics and policy. Some critics argued that even if nudges are usually used for good, they could also be used to manipulate. Nudging deeply explores this idea, highlighting how we can distinguish between what Viale calls “nudgoods” versus “nudgevils” (157) so that we may strengthen the autonomous decision-making process of individuals without manipulation.

One of Nudging’s most insightful discussions revolves around the idea that despite the policymaker (or choice architect) having great power over human behaviour, they are not exempt from the irrationality and cognitive biases

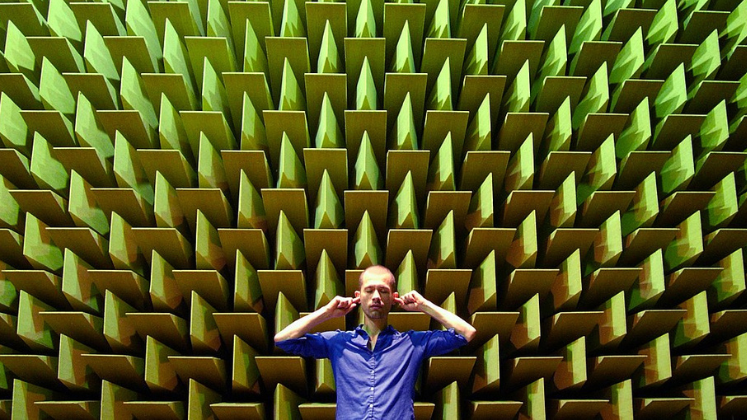

One of Nudging’s most insightful discussions revolves around the idea that despite the policymaker (or choice architect) having great power over human behaviour, they are not exempt from the irrationality and cognitive biases that can affect the decision making of regular individuals. Phenomena such as groupthink and confirmation bias can impact the design and implementation of behavioural policies. As a result, irrational tendencies in government actions may arise, for example in the selection of information that enters policymaking agendas. Hence, the presence of distortion in nudges is problematic as it implies the possibility of “nudgevils” that come from policymakers themselves.

Viale’s critique in Nudging revolves around the libertarian dimension of nudge theory, as well as the S1 and S2 brain functions proposed by Kahneman. The popular argument propagated by Thaler and Sunstein’s Nudge – which posits nudges as libertarian because they do not take the freedom of choice away from individuals – is based on the constraint that nudges are reversible. Viale, however, argues that overriding automatic S1 decisions through rational S2 mechanisms is incredibly difficult. He explains that much of behavioural economics mistakenly applies economic rationality to human decision-making, where the individual chooses from limited options with known calculated risk. In reality, our decisions typically occur under uncertainty and noncalculable risk. This is why our decision-making is heavily dependent on heuristics (shortcuts that enable fast judgments and problem-solving), biases, and other methods that help simplify and adapt to the scenarios at hand. And so, we return to how the “nudgers” themselves are equally susceptible to these shortcomings: Viale’s Nudging suggests that policymakers should shift from nudges rooted in traditional hedonic paternalism (coercive without appealing to conscious awareness) to an educational paternalism that boosts the individual by increasing their independent reasoning and strengthening their decisional adaptability.

Viale is essentially saying that humans do have the capacity for rationality, and that if they are empowered to make decisions on their own, there won’t be any necessity for libertarian paternalist nudges.

Viale’s suggestion to adopt educational paternalism is a critique of Thaler and Sunstein’s paternalism, which considers the human to lack the necessary levels of rationality to make smart choices independently. The idea of choice reversibility that Thaler and Sunstein argue is a necessary condition to satisfy the libertarian dimension of nudge theory is therefore undermined if the individual does not have enough rationality to go against the nudge, despite their freedom to do so, as they are limited by human inertia, weakness of will, and biases such as status quo. In this circumstance, the only ones who can easily reverse libertarian paternalist nudges are those who have the cognitive ability and willpower to choose the best options by themselves, or in other words, those who do not need to be nudged altogether. In Nudging, Viale is essentially saying that humans do have the capacity for rationality, and that if they are empowered to make decisions on their own, there won’t be any necessity for libertarian paternalist nudges. Rather, nudges that focus on adaptive rationality, perhaps through the simplification of information, will allow us to make the best decisions for our welfare, even under time constraints and limited computational capacities, improving our contribution to society as active participants.

Viale suggests nudges should boost individuals through a process of intellectual empowerment to equip them with rational adaptability, without encroaching on humanity’s natural tendency to use one’s own heuristics and adaptive inclinations.

Viale’s Nudging is a great read for anyone interested in learning more about nudging philosophy thanks to its engaging writing style, and particularly because it excels at being relatable through timely examples of how to identify nudges in everyday life. Viale’s major recommendation is to provide individuals with the tools necessary to self-nudge, debias, and dodge nudges that come with distortions, enabling a form of conscious decision-making. As an attractive end goal, Viale suggests nudges should boost individuals through a process of intellectual empowerment to equip them with rational adaptability, without encroaching on humanity’s natural tendency to use one’s own heuristics and adaptive inclinations. In doing so, Viale’s Nudging achieves a notable revisitation of behavioural economic ideologies, making it essential reading for those interested in the behavioural sciences and their wider application.

The content generated on this blog is for information purposes only. This Article gives the views and opinions of the authors and does not reflect the views and opinions of the Impact of Social Science blog (the blog), nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Please review our comments policy if you have any concerns on posting a comment below.

Image Credit: pogonici on Shutterstock.

I have not read the book, but it seems like the author is trying to have it both ways – yes, people use short cuts and have cognitive biases that have been ignored by economics with its reliance on rational calculation, but these can still be overcome by education. By all means let’s have better education, but much of the evidence in choice behaviour is that education targetted at specific behaviours has limited impact when set against the predominant inertia of the choice architecture with which individuals are routinely faced. And let’s remember that when there are commercial principles at play, the choice architecture is usually already structured to nudge or shape the individual in the interests of those with money at risk. So, for example, why do people find chocolates and the like at check-out? How do savers weigh what appear to be the tiny fees they are paying against their cumulative impact in greatly reducing long-term retirement incomes? There’s a big bad world out there with vital commercial interests at stake. An excessive commitment to libertarian ideals plays into their hands as they joyfully set up choice architectures that your average consumer finds hard to parse. But then maybe it is just enough to inform people of the old Latin phrase “caveat emptor”.

I haven’t read the book, I’m not a behavioural economist. The point made chimes closely with the information deficit theory. It’s proven every day that people have all the information they need and still do not ‘behave’ accordingly (fast food consumption, physical exercise to name a few). In public engagement with research we need to find a ‘hook’ (like our journalistic colleagues) that appeals on a personal and emotional level with people, otherwise people don’t care. Once they care, they are more motivated (to act- hopefully).